Brazil and India Usher In The Open Finance Era

~8 min read

It took a few years of discussions, proposals and frustrations for open banking to become an actual, concrete trend in financial services. Yet before open banking has reached all markets, let alone maturity, here we are, talking about the next step: open finance. And while relatively few still know what open finance even is, this intermediary step is arriving faster than open banking’s fits and starts may have led you to believe —if with new challenges that come with a widening, complexifying data-sharing regime.

One Small Step For Data

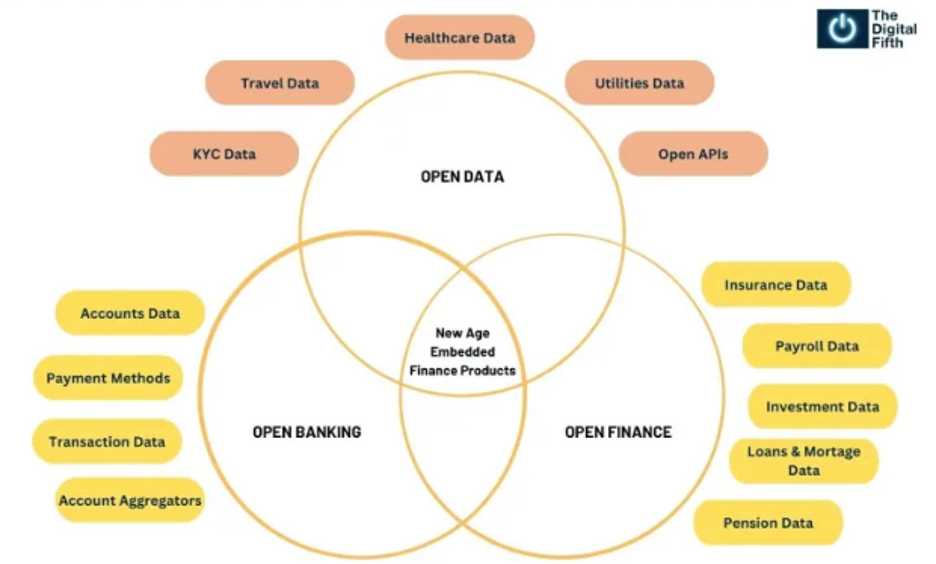

Open finance takes the key principles of open banking — open payment data sharing between financial institutions — and takes it further to encompass all kinds of non-banking financial data.

Source: The Digital Fifth

Source: The Digital Fifth

Exact delineations may differ somewhat, and that’s because API-enabled transformation has become a piece-by-piece expansion — but discussions for many countries now center around open finance.

The UK, the first to initiate open banking, is aiming to implement open finance, as is the EU, which is forming a host of regulations to enable and oversee this expanded open data sharing environment, including PSD3 and the Financial Data Access (FIDA) rules on the precipice of adoption.

Sprinkled around the globe are early examples of initiatives, including Australia — which has already targeted Open Energy functions within its data-sharing infrastructure— and South Korea, which is now more than 10 years into adopting its evolving plans to complete an open data regime. In all, 69 countries had open banking regulations on the books at the start of this year, with another 18 employing a market-driven approach to enabling open banking, including the U.S.

But when it comes to transitioning towards an open finance terrain, none have done it faster and more impressively than Brazil.

After a slow start, India, another early adopter, has seen an uptick in open finance adoption in recent months — thanks to its account aggregators picking up steam and India’s digital public infrastructure firing on all cylinders. Relying on voluntary participation from institutions, however, India’s consumer adoption of open finance did not take off as fast as Brazil, where there were 29 million active users per month in open finance frameworks at last count.

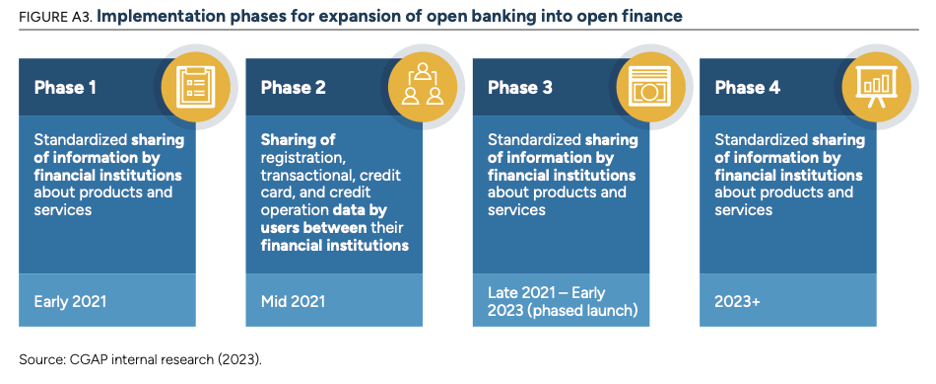

Brazil’s open finance journey has been done in phases, beginning implementation in 2021 and adding use cases along the way.

With Brazil taking the lead, countries in their discussions are coalescing around a phased approach to open finance and, as an extension, open data eventually. But it takes time.

“More countries now are already thinking about open finance from the beginning (versus open banking), but that doesn't mean that that's how they're implementing it [right away] — it's a phased approached.”

Maria Fernandez Vidal, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, CGAP

One Giant Step For Data-Kind

Going beyond banking data into all financial aspects, such as tax or payroll data, gives third-party providers a 360-degree view into an individual or business entity’s financial status and patterns, enabling tailored products and services. And most importantly, the framework completely empowers individuals to share their data as they please to a third-party provider, levelling the data playing field.

In the case of Brazil, the open finance framework is constructed in a way so that there is no central intermediary facilitating the data-sharing; everything is API-enabled, with reciprocity a requirement.

Fernandez Vidal notes that while data-driven innovation of products in the past couple years have largely been through bilateral arrangements, such costs for challenger institutions vanish under this open finance scheme, setting the stage for third-party providers to excel at their market niche and press innovation forward.

“[Bilateral agreements] take time. It creates costs. But with open finance, it's the same rules for everyone. It just really lowers the cost of that innovation.”

Maria Fernandez Vidal, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, CGAP

Not Because It Is Easy

But expanding beyond banking data into all kinds of financial data creates a daunting layer of complexity in navigating the labyrinth of regulations and data types the widening apparatus includes. The ascent of AI tools should provide a feedback loop in comprehensive data sets fueling AI capabilities which can in turn analyze disparate data sets to discern patterns and fitting solutions. But the open finance frameworks should be thought of as living, breathing infrastructures adapting to new market characteristics and readiness; CGAP recently released an “open finance self-assessment tool” to help countries understand how ready they are for open finance — and how to get there.

As essentially an intermediary step in the evolution towards open data regimes, there is no “leapfrogging” from nothing to open finance. It is the culmination of years of regulatory and market development. But getting the infrastructure right isn’t enough. Open finance relies on network effects to spur competition and innovation within a given market to bring down costs and reach otherwise excluded (or barely included) populations. That requires proper design, incentives (or requirements) to participate and market conditions enabling adoption at a critical mass.

In a paper published this March, Maria Fernandez Vidal, a senior financial sector specialist with CGAP, identifies along with her colleagues three building blocks.

- Broad access to digital accounts that builds confidence in digital systems and creates a digital trail of transactions that can be shared as data by the user.

- Fast (or instant) digital payments that are low or zero-cost, which drives digital account usage and the digital trail of transactions.

- A diversity of providers that enables the competition required for an open finance environment to reap its full potential benefits.

When viewed from this framing, Brazil and India were the perfect candidates for open finance to take off. India took a big step forward in its digital journey when it launched the Jan Dhan accounts in 2014, which went on to provide financial accounts to more than 350 million Indians. Brazil, likewise, saw in 2016 the approval for financial accounts to be opened digitally, creating “a low-cost, far-reaching set of access points,” spurring an increase in financial account ownership to reach 96% of the adult population according to CGAP’s 2023 survey.

The next aspect — low-cost instant payments — is among the crown jewels of Brazil and India’s digital financial revolution, in particular Brazil’s PIX and India’s UPI. Both have turbocharged participation in their respective digital economies and provided a foundation for competition and innovation that bleeds into the third requisite building block: a diversity of financial service providers. The 2023 CGAP survey found 92% of Brazilian adults with a bank account — 88% of all adults — used PIX, and in India, UPI now facilitates more than 10 billion transactions per month.

All of this have contributed to dynamic, competitive digital ecosystems in both countries, where no single entity can dictate terms working against the efficiencies provided by a competitive open finance environment.

Slow And Steady?

Implementing open banking 1.0 and achieving mass adoption requires those market reforms to come into place first — a task that is still ongoing in many places. Trailing countries adopting open banking have learned the lessons of trailblazers like the UK, and experts like Vidal expect the transition to open finance to be quicker with those building blocks already in place. As an intermediary step towards the ultimate aim — open data — open finance is simply the expansion of what’s enabled under open banking.

But that doesn’t imply smooth sailing to an eventual open data world. Even in India and Brazil, there is still a long way to go for mass adoption; only 11% of adults in Brazil surveyed by CGAP in 2023 said they were participating so far, though that figure has likely grown. With adoption lagging especially among poorer adults and women, those who haven't yet adopted open finance mechanisms cite in CGAP surveys concerns like security and perceived need for failing to make the jump.

By its very nature, the uptake won’t be quite as fast as Brazil experienced with PIX already.

“[Open finance] is more of an ecosystem that powers different products, but it's not as simple for people to understand because it is not a product in itself like PIX or UPI payments. Having fast payments before was really helpful in both markets, but with open finance it takes some time to really develop the value proposition and use cases to drive higher levels of adoption.”

Maria Fernandez Vidal, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, CGAP

Getting things right like consent — which must be revocable at-will if open finance is to work as intended — will take time as regulators walk a thinning fine line. Data protection regulations like the EU’s GDPR, which is replicated to a great extent in India, Brazil, and many jurisdictions elsewhere, largely don’t provide quite the detail required to effectively oversee a complexifying system of data exchange.

“Even a mandatory [participation] scheme is unlikely to regulate [data sharing] at a very granular level. There's a trade-off between [standardization] and innovation because if you mandate a standard, there'll be less incentive, perhaps no incentive for people to experiment and try different things.”

Konrad Borowicz, Assistant Professor of Financial Regulation, Tilburg University

These obstacles only loom larger as these forerunners add more sources of data to their infrastructure. For observers like Borowicz, this next step past simple payments data into other realms reveals a tension between the ambitious aims and endpoints of open finance and the challenging institutional reality of implementing it.

“How open do we really want it to be, and what are some of the obstacles that exist? Even in Europe, where the legal framework for open finance is most advanced, I don't see there being that much clarity on what we actually want open finance to be.”

Konrad Borowicz, Assistant Professor of Financial Regulation, Tilburg University

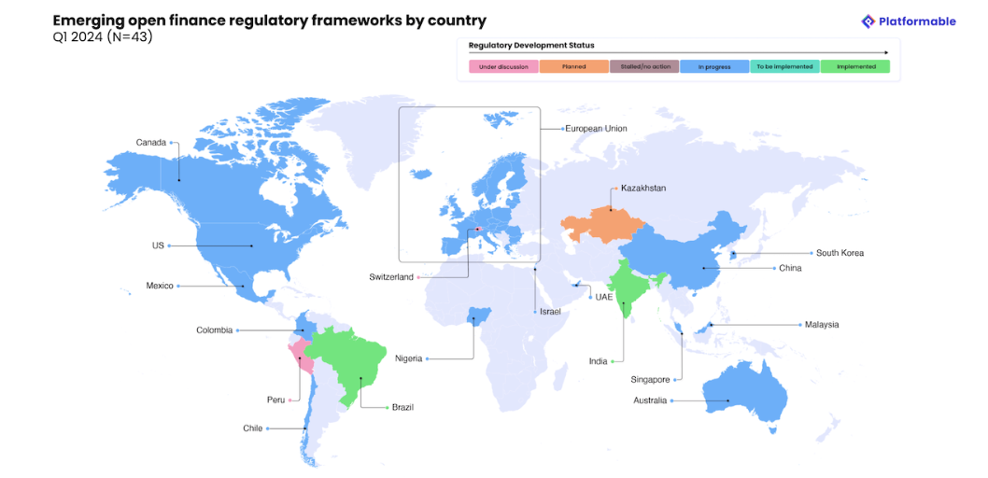

While unresolved questions remain, dozens of countries have already adopted open banking, with many more under discussion or at the implementation stage. With the kinks worked out through the early pioneers like the UK, the pace will only pick up further.

Source: Platformable

Source: Platformable

Getting all the players in line will be a tall task early on, though Fernandez Vidal is confident that a growing pie will help get on board even the data-rich big banks that stand to lose their data advantages compared to competing challenger institutions; in Colombia, Vidal says the big banks are among the biggest advocates of pushing for an open data regime.

“For [Colombian big banks], their interest is when they can get outside of the banking sector. That allows them to reach people that are not fully banked or that may not be transacting digitally. If anything, expanding the scope should help get that interest from the banks.”

Maria Fernandez Vidal, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, CGAP

Once the building blocks are laid, there will be some differences in order or emphasis in how these data regimes will expand; telco data will likely take priority in mobile money-heavy East Africa, for instance. But if even achieving market readiness for open finance marks an accomplishment in itself, fully implementing it will transform digital financial networks tenfold, if with a behind-the-scenes subtlety.

Image courtesy of Viktor Forgacs

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Betting on Chaos: Africa’s Thriving Online Gambling Industry

Fintech And The Era of Digital Public Infrastructure