Bridging The Access-Usage Gap, Literacy Efforts Aren’t Key — Addressing Need Is

~8 min read

Even following COVID’s turbocharge of digital uptake, the slower gains in usage compared to access renders financial inclusion efforts a work in progress 15 years after M-Pesa’s launch. For years, a great degree of blame has been pinned on the lack of financial education and literacy among the financially excluded — the implicit point being that we know better than the poor do regarding what’s best for them financially. But do we?

The gap between financial access and usage is such a recycled topic that the proposed solutions have gone stale, repeating mantras from 2019 tailwinds even during 2023 headwinds. Indeed, closing the financial access and usage gap requires an “all-of-the-above” effort varying by the national flavor of needs and market characteristics. What’s really needed, however is a philosophical shift away from trying to deliver the right message in the right medium— but delivering the right product.

Access First, Usage Later

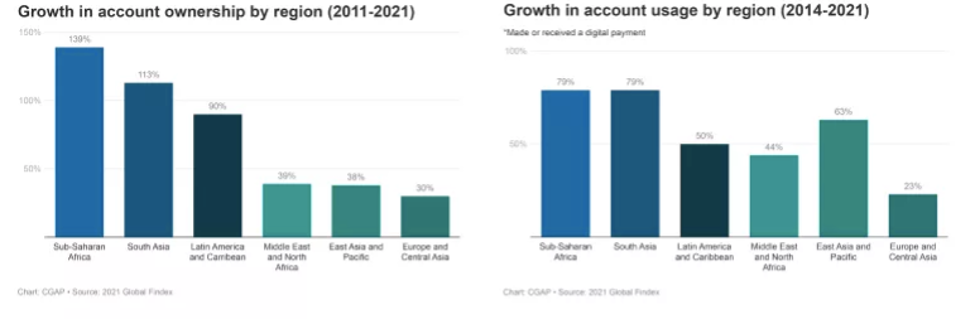

Miserly grumblings of a self-aggrandizing fintech revolution gone astray underscore the significant strides that certainly have been made certainly in expanding financial access — in some cases dramatically — and to a less extent usage as well. According to the World Bank’s Findex 2021, global account ownership increased from 51% to 76% from 2011 to 2021. On the usage side, while 36% of account owners in developing economies did not make or receive digital payments in 2014, that figure dropped to less than 20% of the quickly growing pie of account holders by 2021.

The financial inclusion mission has really evolved in two stages: access first, usage later. Initial efforts to expand access to financial services produced impressive gains in terms of raw account ownership, but it also precipitated a rise in dormant accounts. India stood out for its Jan Dhan Yojana program, beginning in 2014, to provide financial accounts for the country’s unbanked, expanding account ownership by over 400 million people. But a year after its launch, half of the Jan Dhan accounts contained no balance, famously leading banks to add one rupee to such accounts to distort usage statistics.

“It is obvious that someone needs to be able to access something before there's any chance that they can use it. But by thinking of it in that two stage way, what’s lost is [thinking], ‘why do people use something?’ It's not just because they have access to it.”

Jeremy Gray, Technical Director, CENFRI

It was about five years ago that policymakers really began to focus on coaxing new account holders to go beyond simply cashing out. Shifting policies to foster meaningful uptake gave way to the real catalyst for accelerated adoption since then: COVID. According to the IMF’s 2022 Financial Access Survey, between 2019 and 2021 , the value of mobile money transactions increased from about 40% of GDP to 70% of GDP in low-income economies.

COVID is the most obvious example of what Thorsten Beck, Director of the Florence School of Banking and Finance, frames as “teachable moments”: circumstance that call for crucial, even novel, financial behavior.

“When you [try to educate] people in the moment where they actually need to use these financial services, that then really seems to click and make them more careful and more conscious of the way they use the financial services.”

Thorsten Beck, Director, Florence School of Banking and Finance

The Financial Literacy Excuse

Massive adoption took place in sectors where COVID lockdowns had the most impact in consumer behavior and habits, like payments and ecommerce. But the gains felt in areas like insurtech have been far less. Inclusive efforts continue to fall short especially when it comes to those most at risk, the so-called bottom of the pyramid.

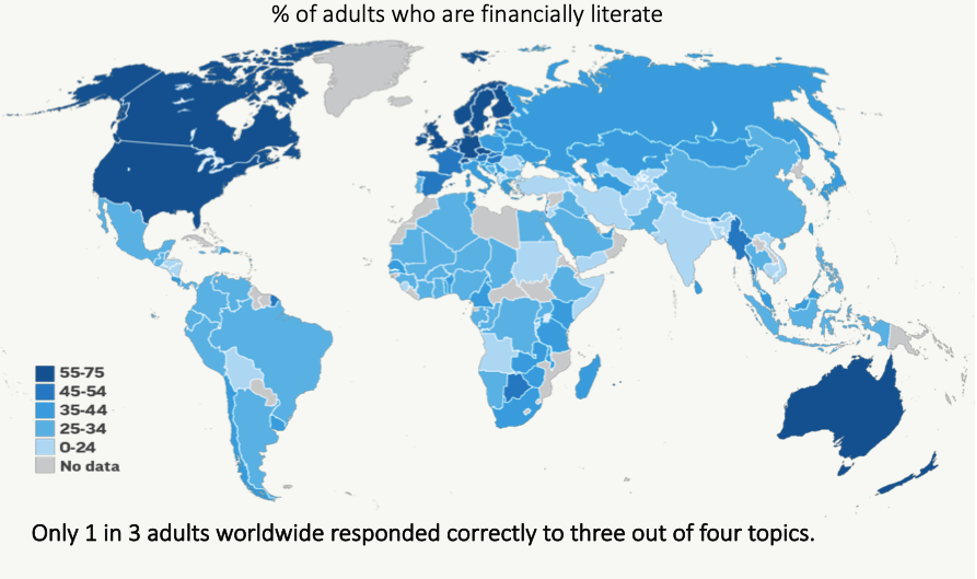

Often, why that’s the case has been attributed in large part to disturbingly low levels of financial literacy.

Source: Annamaria Lusardi, via World Bank

At this stage, insufficient financial literacy doesn’t result so much in non-usage, however, but ill-advised usage.

“Before, it was about how to open an account, compounding interest, fee structures and so on. Now, it's about how careful you have to be in terms of accessing financial services through the Internet.”

Thorsten Beck, Director, Florence School of Banking and Finance

African insurance executives would tell Jeremy Gray, Technical Director at CENFRI, that people aren’t purchasing their products because they don’t understand the product or its value due to a lack of financial literacy. When he asked the executives if they had insurance themselves, many didn’t. “And why? Because the value that insurance offers [compared to] informal insurance products,” said Gray, “is often very poor.”

A qualitative survey in Guatemala from USAID found that while financial providers cited low confidence and limited education as the main barriers to access and use among low-income individuals, it was actually non-transparent banking fees proving to be the greater issue — a trust issue of their own doing.

Studies over the years like the Financial Diaries project have shown how poorer segments need to be even more conscientious in managing their finances, often using more financial solutions — either formally or informally — than wealthier counterparts in developed markets.

Informal financial instruments like hawala money transfer systems and savings clubs persist not because people are stubborn, but because such services, in spite of its risks and high costs, still provide comparable strengths to digital options, like cash’s universal acceptance at no explicit cost.

Low-income people are not not using financial services because they don't know about them, because they don't understand them, or because there's a lack of literacy. And they're not necessarily not using them because they can't access them. They're not using them because these [products] aren’t meeting their needs.”

Jeremy Gray, Technical Director, CENFRI

For all the lip service done in the name of localized, tailored products, the formula for products and ecosystem development too often is constrained to a one-size-fits-all paradigm that neatly reflects Western aspirations rather than local needs. Gray offers the example of a large transport company in Africa that did not have any other form of motor vehicle insurance beyond compulsory third-party motor vehicle insurance. What they did have, however, was a fleet management tracking solution that proved valuable in managing its unique risks. “They were very aware of the risks, and they were taking very clear steps to try to manage and mitigate those risks,” says Gray. “But insurance was not considered a value proposition to respond to the risks.”

A management tracking solution, Gray posits, might better address immediate risks to a logistics company than an insurtech product with a dubious value proposition. From there, bundling can serve as a pathway to complement preexisting solutions with more formal tools.

An Instant Payments Foundation

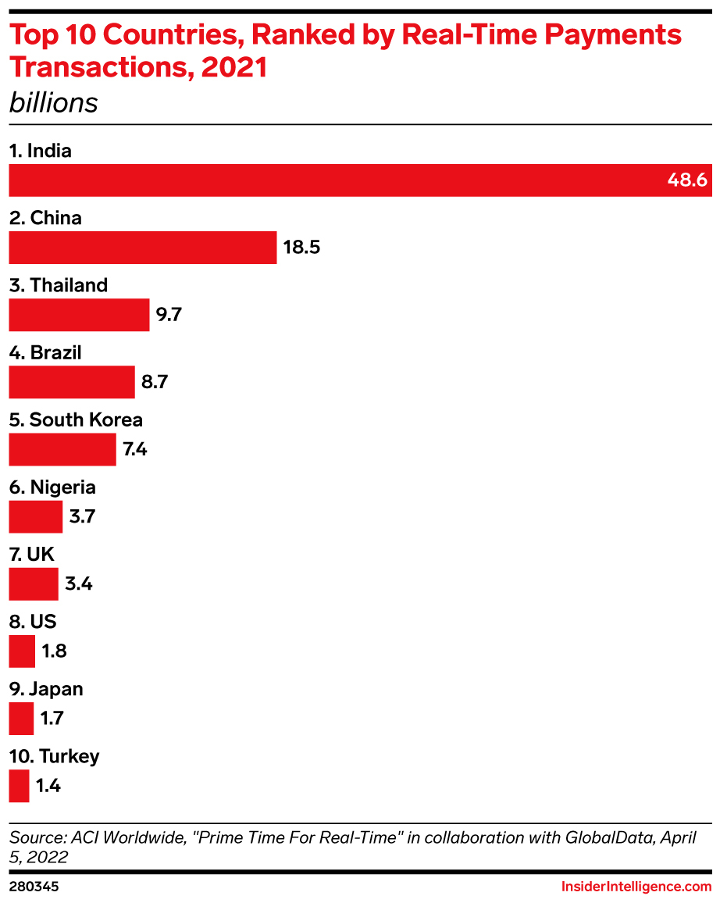

If digital payments are the entrance to financial participation, low or zero-cost instant payments are what really bring people through the door. Brazil is one standout example, yet the long, winding road India took, from hundreds of millions of dormant accounts to digital payments ubiquity through its United Payments Interface (UPI), is instructive.

Anit Mukherjee is a Senior Fellow at ORF America, and he has been associated with Aadhaar and UPI from their inception. In a departure from the conventional approach, UPI was designed not a platform-driven system, but a protocol-based one providing a shared public infrastructure.

“There is no other way that you can have an expansion in usage if you only build for a small segment of the population. And that's the problem with privatized digital infrastructure. The companies will only build for what they think they can service or what would be their customer base.”

Anit Mukherjee, Senior Fellow, ORF America

UPI has famously facilitated a massive shift in how Indians transact, onboarding even the elderly and poor to make payments to street vendors using UPI. Doing so with (on paper) a still financially undereducated populace hasn’t really stopped meaningful adoption from taking place.

“A lot of financial education has happened through usage, and people are not unaware anymore… I think that is something that is not well reported — people are getting financially savvy, because they have a bank account, and they're transacting digitally. Now's the time to build on that to go to the next level.”

Anit Mukherjee, Senior Fellow, ORF America

An instant payments framework alone isn’t a panacea for the usage issue. Indians were already being primed to reconsider the value proposition of digital payments over cash starting with the government’s radical demonetization efforts that artificially created a need to make payments in ways other than just cash. UPI’s massive success didn’t happen all at once — it was the culmination of a yearslong effort addressing access and creating a well-designed, trusted public infrastructure to make it work, undergirded by the Aadhaar biometric ID system.

Though deepening inclusion is starting to take shape, payments have matured faster than other digital financial products in India. Mukherjee doesn’t see a public instant payments infrastructure like India’s UPI as a solution in itself to address areas like credit or insurance. But it can serve as one foundational layer for additional protocols to be implemented. Account aggregators, for example, have grown tremendously since being launched by the Reserve Bank of India in 2021, with 1.1 billion accounts created through India’s Account Aggregator ecosystem.

In India’s instance, indeed, access is directly connected to usage. But crucially, expanded access really does come with an improving value proposition for consumers. This is thanks to superior economies of scale that’s much easier to achieve in India than elsewhere. To replicate that in other environments, expanded access and usage calls for data-driven solutions tailored to the individual level.

CENFRI’s Gray cites the Kenyan Tea Development Agency Tea Association as one success story to overcoming issues of sub scale. In Kenya, one survey found that while over 82% of farmers use mobile financial services, fewer than 15% of them use mobile financial services for agricultural purposes, often finding little use for what’s available. In the case of the tea association, however, the aggregation of the digital payments of 600,000 small tea growers provided the kind of data and aggregated group of customers with similar needs necessary to create well-tailored financial solutions.

To accomplish these gains in meaningful adoption, there likely won’t come another COVID-like event suddenly driving a “need” for digital financial services. With the funding drop and increasing emphasis on short-term profits, we may be entering a frustrating period where efforts to close the access/ usage gap stagnates as banks double down on servicing the most profitable and least risky.

But chaos can be a ladder. Recent successes will beget further expansion of public infrastructure to enable attractive, low-cost services. Competition from fintechs motivates financial institutions to better address the needs of those who may be otherwise categorized — rightly or wrongly — as the “voluntarily excluded.”

Image courtesy of John Towner

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Inclusion Through Gig Work: A Tricky Venture

Venture Philanthropy: Data for Good?