Brazil’s Pix: Should Instant Payment Rails Be A Public Good?

~7 min read

When Mondato Insight last discussed instant payments in Brazil in 2020, Brazil’s central bank had unceremoniously ended WhatsApp’s own payments scheme there, citing anti-competitive dynamics — as the Banco Central do Brasil was about to unleash its own instant payment scheme, Pix. What looked to some then as government interference favoring its own scheme over private sector options now looks like necessary groundwork for a countrywide, interoperable instant payment rail — and subsequent transformation of the country’s digital payments ecosystem. Pix has been an unabashed success, with massive adoption fundamentally changing how Brazilians transact. Though there are precedents for government-backed instant payment schemes, Pix is arguably the first to be wholly central bank driven, regulated, and operated, successfully overcoming many of the hurdles that befell other countries. As the foundation for a proliferation of innovation and expanded use cases from the private sector, Pix offers a compelling road map for other countries to approach instant payment rails as a public good, implemented best from centralized, nonprofit entities like central banks.

The Public Picks Pix

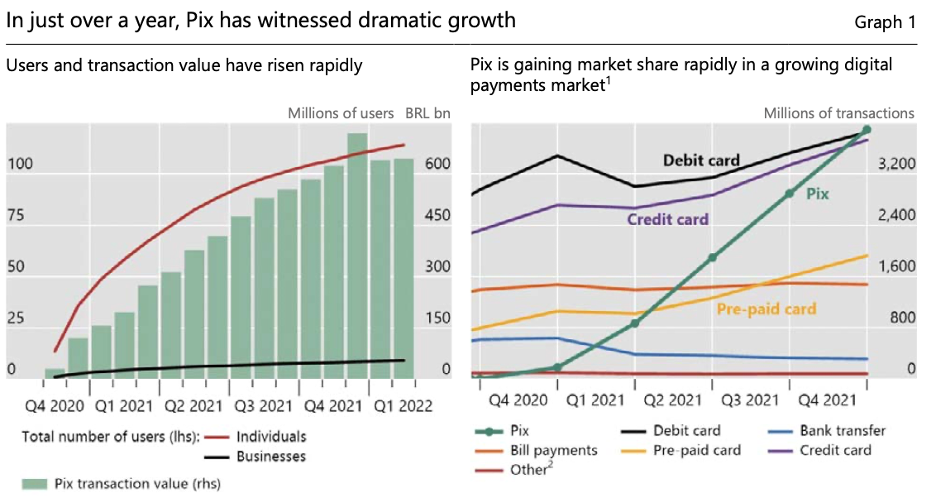

While earlier instances of successful instant payment systems warrant comparison, the rapid adoption and transformation of Banco Central do Brasil’s Pix has been with little precedent. 15 months after Pix launched in 2020, the Bank for International Settlements found that 114 million individuals, or 67% of the Brazilian adult population, had either made or received a Pix transaction. 9.1 million companies, or 60% of firms with a relationship to the national financial system, had signed up. The transformation is seen across society — street vendors or performers accept payment via Pix, with the informal economy benefitting tremendously. As one Brazilian describes it to Mondato Insight, Pix now “feels like air” in Brazil: “it’s so common people already take it for granted.”

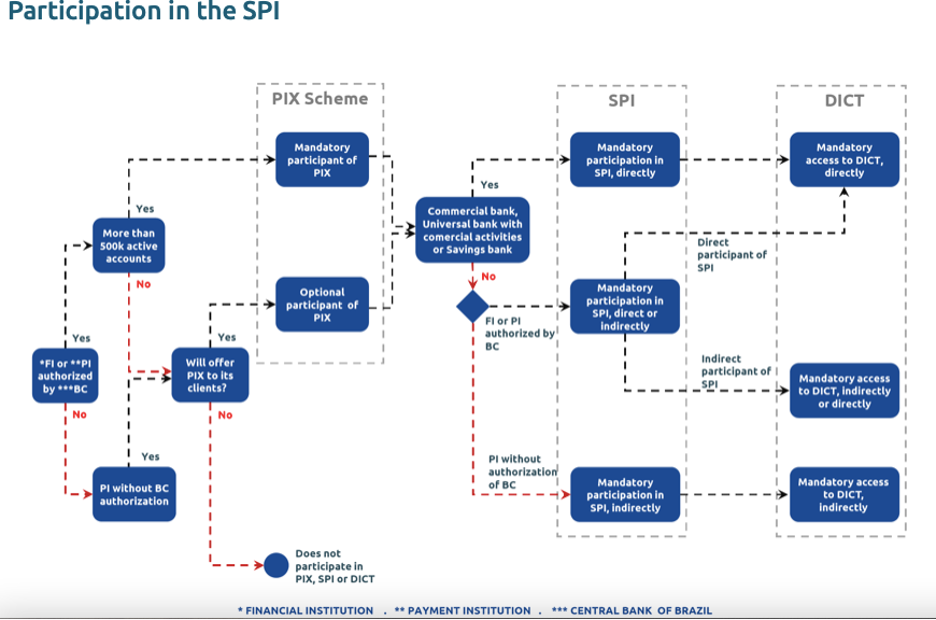

Hindsight is 20/20, but both the conditions and framework were optimal for Pix to take off. In 2019, 77% of retail transactions were cash-based, in spite of frequent cases of theft. The digital payment system remained woefully fragmented, with no interbank direct-debit scheme existing. While Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) played a heavy hand in ensuring Pix’s prominence ahead of other potential competitors— the WhatsApp case being the most prominent example — Pix’ rapid ascent was fueled by its mandate on big banks to integrate Pix. All financial institutions, including traditional banks, digital banks, fintechs and credit unions, were engaged to participate.

Source: Banco Central do Brasil

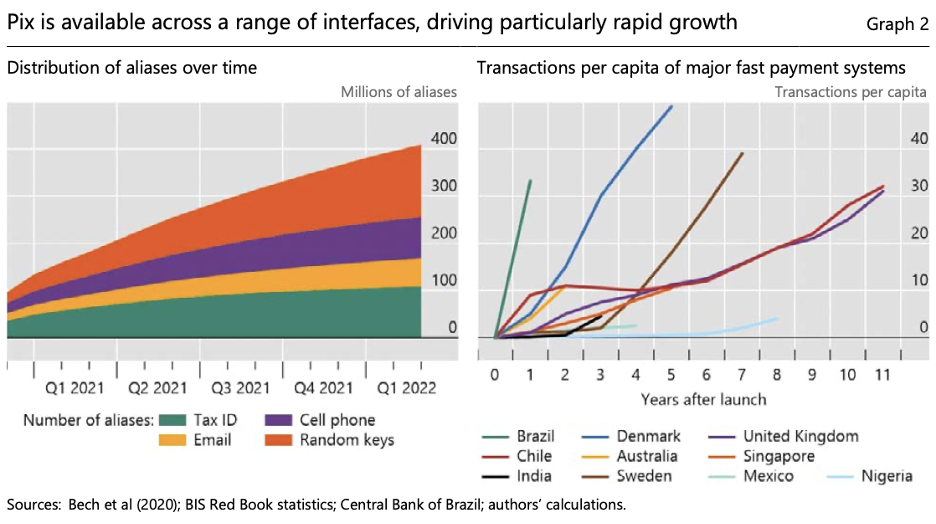

Brazilians found Pix to be extremely easy to sign up and use; all that was required was a phone and payment account with one of the nearly 800 Pix participants spanning the financial system to sign up, with a QR code, phone number, email, or several other personal identifiers being sufficient to initiate transactions. Customers aren’t charged anything, while payment service providers (PSPs) are charged only BRL .01 every ten transactions to cover the costs of running the payment rails.

Along with its convenience and 24/7 availability, Pix proved to be so cheap, BCB had to adjust PIX’s early service after people began to use Pix to send messages to each other as a cheaper alternative to conventional digital messaging services. Merchants also gravitated to Pix and its average cost of .22% compared to fees of 2.2% for credit cards in Brazil. Powerful network effects quickly took hold, as smaller financial institutions not mandated to participate integrated with Pix anyways to remain relevant in the quickly shifting landscape.

It wasn’t simply that Pix replaced more costly and less efficient digital payment methods — Pix significantly enlarged the number of digital transactions taking place. According to the Bank for International Settlements, while Pix partly substituted for other digital payment instruments such as bank transfers — previously noted for their high fees — the total level of digital transactions has risen significantly. Pix transfers were made by 50 million individuals — 30% of the adult population — who had not made any account-to-account transfers of any kind in the year prior to Pix’s launch.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

The widespread (and still increasing) adoption of Pix is further buoyed by its utility in a variety of services, with layers continuously being added to the tech stack. Among its features, Pix allows the transfer of funds between government, individuals and companies alike, with the payment of invoices streamlined to allow for the automatic calculation of fines, interest and discounts. Such simplified payment rails have proven pivotal to small business owners like Fernanda Richard, who runs a small architectural firm in Rio de Jañeiro.

“Before Pix, we had to register each customer in our bank: with branch and account number, full name, company or individual number, and there was a fee for extra transactions. And with Pix, you don't have to do any of that. It became faster and more practical, as the registration is done through an identification number, e-mail or QR-code, in addition to being free or a lower fee compared to [previously].”

Fernanda Richard, Small Business Owner

Greatly increasing the digital payments pie has subsequently converted the banks, initially wary of covering integration costs and losing out on bank transfers, into Pix supporters. In the first quarter of 2022, the four largest banks in Brazil saw 25.4 billion reais in revenue. Though down 5.7% in revenue from the previous year, these banks actually recorded a net income of 24.3 billion reais: a record profit. As it attracts more customers, Pix enables financial institutions to offer new products and services, such as from Santander, which launched an installment payment method with interest rates of more than 2% per month. According to Banco Central do Brasil chief Roberto Campos Neto, losses in transfer fee revenue has been compensated by these new services, increases in transaction volumes and reduced cash costs for banks.

Going Public With Pix

Pix hasn’t been entirely perfect, and there are valid concerns regarding a centralized payment rail like Pix. Though Pix is far safer than carrying around cash, cases of “lighting kidnappings, which saw kidnappers coerce victims to make Pix transfers and prompted Pix to cap the value of P2P transactions at night. Some question the strength of the system’s KYC protocols, which relies on the KYC methods of the system’s nearly 800 PSPs. Hackers and data breaches have also been reported, though it’s done little to dampen the Brazilian public’s enthusiasm for Pix.

The Central Bank’s earlier decision, citing anti-competitive worries, to prohibit the payment services of WhatsApp — a giant in Brazil’s market — was a direct acknowledgement of how quickly network effects can create monopolistic-like payment markets, which the Bank for International Settlements recently said could lead to higher fees extracted, not less. By serving as both the infrastructure provider and rule setter, Pix essentially violates the free market tenet preaching a separation of regulatory from operational functions to avoid the regulator favoring their in-house operator; through BCB’s actions prior to Pix’s ascension, the regulator clearly did.

Yet rather than enriching the operator, Pix took the profit motive out of it, facilitating a system of financial transaction superior in both efficiency and cost for merchants and consumer. The system is well-designed to provide universally convenient, financially accessible payment rails for all parties of the economic system — a foundation upon which rapid innovation can occur.

“[Pix] has helped in a staggering way to reduce the rent to that payments piece, allowing innovation and rents to move to other parts of the process. And eventually, given that we've now figured out ways to do this in essentially zero cost, or pretty low cost ways, that should be reflected in the transaction itself.”

Lauren Cohen, Professor, Harvard Business School

India's United Payment Interface (UPI), arguably the greatest previous example leading to interoperable and zero-cost instant payments — have largely leaned towards the public domain.

However, Brazil’s Pix system is the first of its kind to be both operated and regulated by the central bank directly, coaxing mandatory participation among major financial institutions. In adoption rates, the results have been without rival.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Does that make such a scheme easily adapted to other countries? Not necessarily. According to Harvard’s Cohen — who has advised numerous countries, banks, and regulatory bodies on such matters, including in Brazil — there are three vital ingredients for such a central bank-driven instant payment scheme to succeed:

- A strong central bank relative to private banks that can successfully dictate policy and compel all financial institutions to do the hard, costly work to implement integrations

- Public trust in the central bank

- The necessary infrastructure to support the instant payments system

Considering such criteria, it is easy to see where adoption can fall short in a place like Mexico, where the central bank didn’t have the teeth to enforce no-fee transactions among banks, or hypothetically fail in a Lebanon, where the central bank is in dire financial straits and lacking trust from its citizenry. With a high mobile/ smartphone penetration rate and a central bank capable of compelling all major financial institutions into the fold, Brazil was well-positioned to do what almost no other country has achieved before: a truly central bank-driven instant payment scheme with next to zero costs for participants, and a system that expanded the digital payments field significantly enough so all players, including banks, could benefit and innovate from a standardized payment rail as well.

As Mondato has previously described, many earlier public instant payment schemes across Asia were often jointly run by central banks and commercial banks. This resulted in the exclusion of non-commercial banks, which kept adoption rates lower and encouraged these schemes — and, specifically, their private bank backers — to push transaction fees higher than what is now seen in Brazil: zero.

The case of Brazil offers a strong example that rather than corruptly blending the interests of regulator and operator, a true central bank-driven instant payment scheme eliminates a profit-driven motive of the operator altogether. A scheme like Pix can serve as the bedrock of next-gen digital transactions, fostering expanded financial inclusion through its zero cost to consumers and merchants while enabling financial institutions to innovate on top of these cheap, convenient, interoperable rails.

These emerging characteristics suggest a novel, 21st century digital public good taking shape. When executed well, central bank-operated and regulated instant payment systems have the potential to follow the same infrastructural developments of government-funded roads and mailing systems that came before them.

Harvard’s Lauren Cohen predicts Brazil’s successful efforts will surely prompt other, once-wary central banks to take the full-throated plunge as Brazil’s successfully done. And with that, more bricks of toll-free digital transactional highways are potentially laid.

Image courtesy of Raphael Nogueira

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

The End Of Mobile Money Agent Networks As We Know Them

Can the ABC Model Power Digital Finance?