What's Up With WhatsApp? A Case Study In Payments

~11 min read

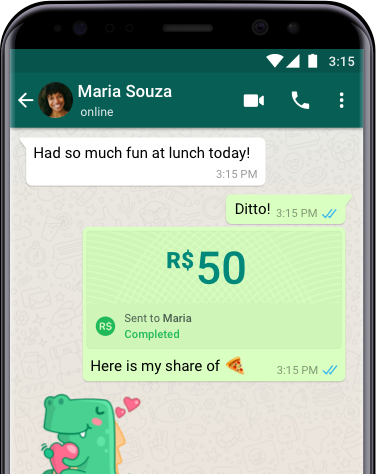

On June 15th, WhatsApp Brazil proudly launched a new digital payments feature--allowing the 120 million monthly active users in the country to use the app to send and receive money instantly. The feature is an integration of Facebook Pay into WhatsApp and is supported by local partner banks and payments provider Cielo. WhatsApp is already a popular, feature-rich social messaging app in Brazil with the potential to take a big slice of a relatively uncrowded payments market. But on June 23th, just a week after its launch, Brazil's central bank, Banco Central do Brasil, and the country's antitrust agency, CADE (Administrative Council for Economic Defense), each suspended WhatsApp Pay, bringing the new feature to halt; Banco Central ordered Mastercard and Visa to stop payments on the app, while CADE opened an investigation into the potentially anti-competitive agreement between WhatsApp and Cielo. So why the sudden conflict? It is in fact a case study in the dynamics of the escalating tension between powerful global tech companies and local public institutions in emerging markets, with economic advantage and consumer data hanging in the balance.

WhatsAppened?

The surprise moves from both Banco Central and CADE prompts many questions and may signal a shift in feeling towards Big Tech inching towards “Super App” status in emerging markets. The central bank’s decision comes after Facebook and other American Big Tech companies have faced roadblocks from local governments while attempting to expand their reach and user bases abroad. Increasingly, local governments are finding Big Tech anti-competitive, perhaps even to their own power, and are more actively favoring locally developed alternatives.

WhatsApp first became popular as an alternative to sending costly SMS messages. Allowing users to send texts and make calls for free with an internet connection helped grow WhatsApp’s user base in the country such that today, nine out of ten Brazilians with internet connection use it. And WhatsApp is no longer just for personal communications--it is now also an important point of contact between customers and companies, from national giants like banks to small locally owned and operated stores. Users can do anything from message their hairdresser to make an appointment, share documents before a meeting, rent a car, pay a bill (depending on their bank), or receive emergency aid and other resources during the pandemic.

WhatsApp has already assumed a quasi "SuperApp" role in Brazil, its second largest market, where the arrival of WhatsApp Pay might have seemed like a natural fit in the progression of the app’s centrality to daily life and business-as-usual in Brazil--and perhaps too good of a fit.

Source: WhatsApp Brazil

The suite of services offered by WhatsApp shadows the rise of Super Apps in Asia like WeChat and Alibaba, which each provide a diverse array of products and services that dominate entire industries like messaging, e-commerce, and payments (to name a few). Super Apps function as their own ecosystems where users come for a frictionless experience of a variety of seemingly unrelated activities. The implications of the Super App are many: they can provide simplified user experiences, but they also threaten to shut out competition and have a distinct lack of transparency when it comes to the user data that is collected and how it is used. In the Chinese cases, the state actively participated in the development, protection, and data usage of the Super Apps for political ends. WeChat, for example, uses surveillance algorithms on users both in China and abroad that further enables the surveillance state in China and potentially poses security risks to other countries.

This has been illustrated in recent weeks by India’s recent ban of 59 apps, including WeChat, that it says are illegally transmitting user data to places outside of India.

“The compilation of these data, its mining and profiling by elements [is] hostile to national security and defence of India,” the Indian national government wrote in a press release on June 29th. The incident shows how political disputes have spilled over into international tech. The primary motivation for the ban may have been reactionary to the armed conflict at the Indian-Chinese border, but the issue of data and privacy remains a relevant undercurrent that demands further examination and action.

Concerns about privacy and the lack of state intervention in the development of Big Tech are just two of the theories as to why the Super App phenomenon hasn’t taken off in the United States. Google serves as a prime example of what might be the American version of the Super App because while it offers several highly influential functionalities from the original Google Search to YouTube and Google Ads, among others, these are all housed in separate brands and separate apps.

Another theory suggests that user preferences in emerging and developed economies diverged because they had different technological uptake experiences: users in the United States moved from a desktop to a smart phone and so prefer single-function apps while many users in emerging markets like China started with a smart phone and so have been more open to Super Apps.

But all this is not to say that American Big Tech firms haven’t attempted to consolidate more services onto one platform. American firms have added functionalities for their American users, but often have more success with the Super App model in emerging markets outside of China.

Take Uber, for example, which began as a ridesharing app and now offers microtransportation, food delivery, and a digital wallet. While it has recently abandoned its digital financial services ambitions in the United States, it continued to launch Uber Cash in several African countries by partnering with the Nigerian payments platform Flutterwave.

Not So Rapido

WhatsApp’s parent company, Facebook, has been growing its reach and product suite for years, including the acquisitions of Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014 and the developments of features like Messenger, Facebook Pay, and the digital currency Libra. While most American Facebook users don't use WhatsApp, it is an integral part of Facebook's international strategy.

WhatsApp seems to be moving towards the Super App model because users access WhatsApp's many features within one app. This makes sense given that WhatsApp's primary markets are in developing economies where users are more likely to leapfrog the desktop uptake experience. In the Brazilian context, smartphones are the primary source of internet connection for 60% of internet users. For comparison, smartphones were the primary source of internet for only 37% of Americans in 2019, up from 24% in 2013.

WhatsApp's success in Brazil as a multi-feature app indicates that there is a significant market opportunity for its payments function, especially given that there still isn’t any other major Venmo-like equivalent where people can send and receive money instantly regardless of where each party does their banking. Concern about the market share WhatsApp might enjoy in Brazil was even one of the risks that CADE, the antitrust agency, cited in its June 23rd injunction. Specifically, the risk was the "combination of WhatsApp’s user base and Cielo’s market power."

CADE has since lifted this injunction, but has not yet cleared WhatsApp Pay for operation in Brazil as the agency is still considering whether WhatsApp and Cielo must file with them as a merger. If there were so many issues with the WhatsApp, it might seem surprising for the agency and Banco Central to have made their suspensions only after WhatsApp Pay launched. But WhatsApp and Cielo appear to have attempted to partially bypass the review process.

"A joint submission from Cielo and Facebook to CADE report that they had informally reached out to CADE the day before the initiative was publicly announced. News articles report they did the same with the Central Bank," according to Ana Paula Martinez, a partner and anti-trust law specialist at the Brazilian law firm Levy & Salomão Advogados. This aspect of the timeline shows Banco Central and CADE never received formal processing and didn't have time to review what they did receive.

It Pays To PIX

Complicating the case, however, are Banco Central's plans to launch its own payments offering, known as PIX, in November this year. PIX is an instant payment system that will be operated and managed by Banco Central. It is not intended to be its own app, but will instead be an infrastructure integrated into the platforms of partner businesses and government agencies that enables instant digital payments.

Guilherme Sousa Rocha, a spokesperson for Banco Central do Brasil, wrote to Mondato:

"For the private sector, [PIX] is about stimulating innovation and investment in technology. We are creating a new ecosystem, with a universe of possibilities. It is a new infrastructure and a new environment conducive to innovation and the development of new business models."

Guilherme Sousa Rocha, Spokesperson, Banco Central Do Brasil

Sousa Rocha also emphasized the potential PIX offers for greater financial inclusion in Brazil, where 45 million people don't have access to a bank account and millions more are underserved in terms of financial services. "PIX facilitates financial inclusion not only for citizens, but for small businesses, which often have limited access to credit lines, for example. PIX can be the gateway for institutions to attract new customers and offer other financial services specific to the reality of small businesses and entrepreneurs, such as insurance, pensions, investments, lines of credit and financing."

At the initial press conference, João Manoel Pinho de Mello emphasized the “multiplicity of use cases” for PIX. Using PIX, Brazilians will be able to make instant payments at any time of day for all kinds of services from paying monthly bills to park entrance fees and even taxes. This is a big deal in Brazil, where paying for your monthly “contas” and “boletos” can sometimes require hours of standing in line to pay during inconvenient business hours. Although there are two digital transfer options currently supported by the central bank, TED and DOC, both incur comparatively high costs to customers and must be conducted during business hours. Even then, the transactions could take hours or even days to complete.

Already, Banco Central has published a list of 1,000 companies with which it has agreements and has mandated that any financial entity with more than 500,000 users use PIX. With this kind of power in payments, Banco Central will not only get a slice of every digital payment (even if it is “competitive” relative market alternatives), but also ownership of important consumer data.

Through PIX and the central bank, the Brazilian government will have greater leverage and regulatory power over the future of digital finance in Brazil. By forcing the adoption of PIX among Brazil's most powerful market players and incentivizing adoption among smaller players and individuals with the utility of open instant payments, the central bank will rise with the private market rather than play regulatory catch up as tech outpaces the law.

So when WhatsApp Pay launched in June, it threatened the viability of the PIX ecosystem. Its enormous market share potential could on one hand, detract users in the peer-to-peer and small business-to-consumer segments in instant payments. and on the other, keep a large share of Brazilian people and businesses off the PIX system.

The latter point is line with comments Ana Paula Martinez wrote to Mondato regarding the case:

"The Central Bank has publicly raised concerns on transactions taking place outside a payment scheme registered before and regulated by them and that seemed to be the main reason for them to suspend WhatsApp Pay... It is difficult to say what the outcome of the case will be and its impact over the financial sector. It is important that the platform adopts non-discriminatory policies to avoid market closure allegations."

Ana Paula Martinez, Partner, Levy & Salomão Advogados

The similarities between the products have also raised some eyebrows from local observers like Estadão columnist Celso Ming, who argued that “by far, the main reason for this untimely reaction is WhatsApp's attempt to pour water into PIX gasoline, the Banco Central project that is being designed to perform the same function starting in December.” Ming conceded, however, that the central bank's stated concerns about security and data privacy were likely valid. Facebook and WhatsApp, among other American Big Techs operating overseas, have not exactly earned a positive reputation for consumer protection.

As Celso Ming hinted at in his column, consumers may be faced with a dilemma of entrusting their data to their governments or to foreign and massively powerful technology companies as central banks around the world confront the rising influence of Big Tech in the financial sector. While there are certainly concerns regarding how large, international companies will wield user data and power in country, turning control over to the state comes with its own limitations and risks.

For example, representatives of PIX frequently emphasize customer choice, underscoring that at the end of the day, the individual could still choose to use a method of payment other than PIX. And yet, the decision regarding WhatsApp Pay seems to show that customers will have the choice only between cash, traditional bank transfers, and PIX, as all forthcoming digital payments options will almost certainly come with a PIX integration. Moreover, during the February press conference, representative Carlos Eduardo de Andrade Brandt Silva clarified that data collected through PIX would not be cross referenced or shared with the Brazilian tax agencies. However, at no point was there a more explicit reference to how consumer data might be used by the Brazilian government.

The tension between public institutions and Big Tech is by no means exclusive to Brazil. WhatsApp Pay itself has faced challenges in both Mexico and India, the two other markets where the feature is being tested.

In India, WhatsApp Pay has been running as a pilot since June 2018 and has struggled to gain authorization from the government to expand its operations. India already has a similar concept to PIX, known as the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), that was launched in 2016 by the National Payments Corporation of India, itself an initiative run by the Reserve Bank of India and the Indian Banks Association. WhatsApp Pay India was required to integrate UPI and is only allowed to facilitate peer-to-peer payments.

According to Business Insider, the holdup on WhatsApp Pay in India has been compliance with data localization issues. In February, WhatsApp received permission to expand its initial pilot of one million users to ten million. Further expansion will depend again on compliance issues. Naturally, laws that require user data to be stored locally tend to favor local players in the payments space. The longer WhatsApp Pay is stuck in pilot mode in the Indian market, the more time local alternatives like Paytm have to establish partnerships and gain market share. The Indian government has exercised its power and retained economic control by allowing WhatsApp Pay to operate on its terms and timeline.

Banco Central do Brasil's PIX initiative and current block on WhatsApp Pay could be read as an attempt to achieve similar ends. By incentivizing participation in the PIX system, Banco Central keeps certain data in Brazil and ensures that innovation in digital finance happens in partnership with them, the regulators. It has used its legal advantage to delay the launch of WhatsApp and protect its planned digital financial infrastructure. Whether this will eventually mean the protection of competition, security, and data privacy it says it will remains to be seen.

Late Registration

Ultimately, it seems that WhatsApp Pay will either have to operate within the PIX system, or compete with it. The suspension of WhatsApp Pay ten days after its launch was the first flex of institutional power now being brokered by the Brazilian central bank when it comes to digital finance in Brazil. A WhatsApp spokesperson has since said, “We support the Central Bank’s PIX project on digital payments and together with our partners are committed to work with the Central Bank to integrate our systems when PIX becomes available.” The statement implies that in Brazil, the future of payments (and any business with aspirations for a large customer base, for that matter) will necessarily be integrated with PIX.

In order to return WhatsApp Pay to operation, Martinez said, Facebook will have to satisfy both CADE and Banco Central. First, CADE will have to decide whether a formal competition filing is in order. Then, "if a filing is ultimately submitted, CADE may clear the transaction, block it or impose remedies." Remedies might include stipulations of the kind that the Indian government required, such as localizing data or conforming to the PIX system. Next, "From a Central Bank perspective, the suspension has not yet been revoked and Facebook/WhatsApp will likely have to register before the Central Bank and/or join the PIX payment scheme in order to obtain permission to resume Facebook/WhatsApp Pay in Brazil."

The clashes between governments and technology companies highlighted here are just some of the most recent examples of how regulatory agencies are stepping up to match the impressive power of Big Tech and intercede in the development of Super Apps. But rather than combat these mammoth companies head on with regulations alone, governments are engaging them on the legal front, too. It remains to be seen whether these state-protected enterprises develop into something resembling the Super App model or the Western Big Tech model, or a unique category of its own.

Image courtesy of Lucas Marcomini

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Democratizing Risk: Are Stocks An Instrument For Inclusion?

Easy Come, Easy Go: Customer Churn Amid COVID