Under The Hood of Apple Pay

~5 min read

This Monday past saw the deployment in the US of Apple’s much-hyped mobile payment product, Apple Pay, which, if you believe all that hype, is going to change the payments industry for good (and for the better). It is clear that a considerable degree of confusion still exists around Apple Pay and how it actually works (consider this example from a McAfee analyst talking to a television station in Boston). Nonetheless, Apple Pay being discussed on a breakfast TV show demonstrates that, at last, mobile payments are going mainstream.

The fact that a security expert can take to the airwaves and opine that Apple Pay offers the same degree of security as Target is indicative of the extent to which it is difficult, even for payment security specialists, to convey to a broader public the new departure that Apple Pay represents, at least in terms of security.

How Apple Pay is different

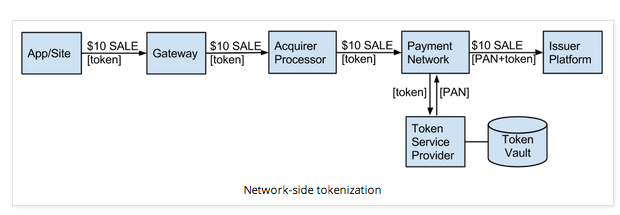

For many years, NFC technology was bedeviled by concerns about both its integrity and the fact that the secure element fell under the effective ownership of the relevant MNO. Apple has changed that narrative through its embrace of both NFC and tokenization, and that is where the Apple Pay model truly holds the potential to be a “game changer”. Apple Pay is significantly different from Google Wallet in terms of how transactions are processed. With Google Wallet, card details are held by Google, and during a payment transaction Google essentially covers the cost of the transaction and then seeks reimbursement from the issuing bank. Apple Pay implements what POS manufacturer Clover has called “network-level tokenization”. And as well as enhancing the security of cardholders’ details, by using tokenization Apple has also relieved itself of much of the regulatory burden faced by “money transmitters”.

As explained in Apple Pay’s security and privacy overview, a much more complex series of communications take place in order to generate the frictionless user experience that is “tap and pay” with the iPhone, and what sets it apart, in security terms, is the fact that your card details are not stored by Apple anywhere. While Tim Cook’s statement during the launch of the iPhone 6 that card payments are “broken” may have been something of an exaggeration, the security breaches at Target and Home Depot (specifically mentioned by Cook in his talk) demonstrated that large cracks are beginning to show. Apple Pay does far more than fill in those cracks, it has instead built a new wall, double-lined with lead.

Tokenization

Perhaps the most significant feature of what Tim Cook and Apple have achieved with Apple Pay is the construction of an entirely new payments ecosystem, involving major players in every stage of the value chain, including the major card issuers, and leading banks that process more than 83% of U.S. credit card transactions. But what has surprised, and even confused some, is the fact that only customers of certain banks will be able to use Apple Pay, initially at least. The reason for this is the tokenization process Apple uses, which sets it apart from its would-be competitors.

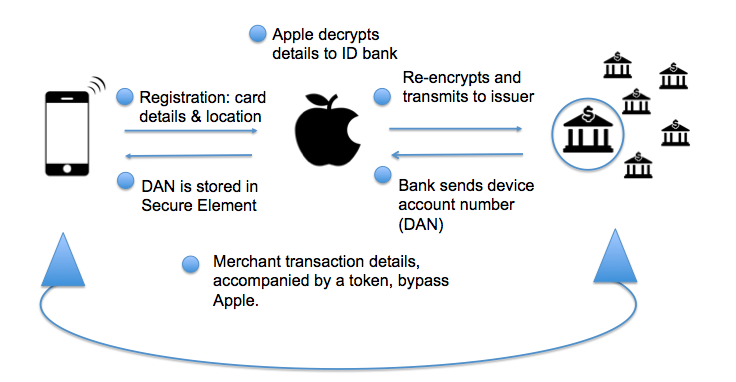

Whenever you enter your card details into Apple Pay, either by taking a photograph of the card, or by manually entering your card details, that data is not stored on your phone, but is encrypted and sent to Apple’s servers. Apple then decrypts the information in order to establish which payment network and bank you are with, and then re-encrypts it and sends it on to your bank, along with information about your iPhone/iPad device, and your current location. If nothing appears to be untoward, your bank should approve the addition of your card to Apple Pay, and then create a Device Account Number (DAN), specific to your phone, which will be encrypted, and sent it back to Apple, along with the key for authenticating the tokens that will be generated each time Apple Pay is used.

Once Apple has received your encrypted DAN from the bank, it transmits it to your phone and stores it on the Secure Element within the iPhone 6. Within the Secure Element DAN sits behind the metaphorical double lead-lined walls, in isolation from iOS. It is neither in the Cloud, nor on Apple’s servers. It resides solely within the Secure Element of the phone, and with your bank. And, of course, one of the other huge advantages that Apple has over competitors is the tens of millions of credit cards that it already has on file with iTunes. Customers setting up Apple Pay for the first time are given the option of using the card on file, and then all they have to do is enter the CVV.

The illustration above, courtesy of Clover, shows what happens when the consumer makes a purchase with Apple Pay, using “network-side tokenization”. After having activated Apple Pay by entering a PIN code, or using a thumb-print in TouchID, a single-use token is generated and transmitted along with your encrypted DAN via NFC and the POS terminal to the merchant’s bank, along with the request for payment. Apple is not involved in this process, and does not receive any information that identifies you and your purchases. Your bank (the issuer) uses the token to verify that the request is legitimately from your DAN, and then approves payment to the merchant (acquiring) bank. At no point are card or account numbers ever transmitted, and the DAN is useless without the authenticating token. Tokens are themselves useless as they can only be used once, leaving, essentially, nothing worth hacking anywhere in the entire process.

iTunes – the chink in the armor?

None of this changes the fact that Apple’s iTunes still stores credit card details on file, and the integrity of those servers remains unaltered by Apple Pay: your card details remain no more and no less secure than they did last week, and this is where the potential vulnerabilities of Apple’s new system may lie. The hacking of iTunes accounts is certainly not unheard of, and because of the integration of the many Apple systems the effects of having your AppleID compromised can extend well beyond having card details revealed.

You can be sure that hackers are right at this moment attempting to exploit vulnerabilities in the Apple Pay system, most likely at the point in the process where new cards are added. However, if Apple’s protocols work as they are intended to, it appears that those hackers are going to have their work cut out for them.

©Mondato 2014. Mondato is a boutique management consultancy specializing in strategic, commercial and operational support for the Mobile Financial Services (MFS) industry. With an unparalleled team of dedicated MFS professionals and a global network of industry contacts, Mondato has the depth of experience to provide high-impact, hands-on support for clients across the MFS ecosystem, including service providers, banks, telcos, technology firms, merchants and investors. Our weekly newsletters are the go-to source of news and analysis in the MFS industry.

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

(Icons: Bank by Narcisse from The Noun Project; iPhone by Oleg Frolov from The Noun Project; Apple by Arthur Shlain from The Noun Project CC-BY 3.0.)

Telcos and the Connected Consumer

eBay Minus PayPal Equals PayPal Squared?