Death And Taxes

~6 min read

Nothing in life is certain, so the saying goes, except death and taxes. It should come as no surprise, then, that mobile money and Digital Finance are making inroads into both of these unavoidable facets of life. Mondato Insight has already touched upon how digital finance is being used to help pay for funerals in Kenya, and more recently how payment of local taxes has formed a major part of the business case for what has become known as the Modelo Perú. In the latter post, we observed that a study by Karandaaz of Pakistan had suggested four factors would determine whether it would be possible to leverage person-to-government (P2G) payments in order to further financial inclusion:

- Strong government and private sector buy-in

- Reliable infrastructure

- An enabling policy environment

- Indications of consumer readiness

But what of the narrower and more immediate target, from the government's perspective, of increasing tax revenues? The theoretical attraction of taxing mobile money in relatively sizeable markets is obvious: high mobile money transaction volumes mean significant revenues can be collected at relatively low rates of taxation, and many citizens who largely operate in the informal economy can be brought within the tax net. For tax-payers, ease and speed of use, along with reliable record-keeping, point towards obvious value added by payment of taxes via the mobile channel. But the technological scrapheap is piled high with ideas that evinced a clear use case on paper. What evidence exists that digital finance helps swell government coffers?

A Digital Cash Cow

In some jurisdictions, the national Treasury has sought to reap immediate dividends from mobile money by imposing a duty or a tax on certain types of digital finance transactions. Notably, in what are probably the two most robust mobile money markets, Kenya and Tanzania, taxes on mobile money now constitute a significant source of tax revenues.

In Kenya, Safaricom is the country's single biggest taxpayer, but the extent to which it dominates the mobile money market means it does not hesitate to pass on new taxes to consumers, such as the 10% duty on transfers over Ksh 101. In neighboring Tanzania, after having lowered taxes on money transfers in 2014, the government has increased excise taxes on cash-out fees. The cumulative effect is that the the country's MNOs contributed >11% of the government tax take in 2014, some US$510m.

By way of contrast, in Uganda, shortfalls in government revenues in 2013 were being blamed on the growth of mobile money services, and the consequent squeeze that this was having on the country's banks. Nevertheless, within a short period of time the Ugandan Revenue Authority (URA) had signed an agreement with MTN Uganda to open up P2G payments to the mobile money channel. (This was actually Uganda's second attempt, following a failed agreement with Warid Telecom in 2012).

Notably, however, the URA took the digitization of its tax payments one step further, and in 2017 launched a national system for paying taxes using Visa or Mastercard - an East African first, claims the URA, in an attempt to increase its regional competitiveness. Despite this, however, consultations have taken place between the governments of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania on tax harmonization in this area, and as of now all three currently impose a 10% excise duty on mobile money fees and commissions, as well as Value Added Tax.

Or Growth Killer

Unsurprisingly, the MNO trade body, the GSMA, has been vociferous over the years in its critique of taxes on both mobile money and the telecom industry more broadly, warning that they were hindering growth and fundamentally regressive in nature.

This was made apparent recently when the Government of Ghana was reported to be considering a mobile money tax as "not a bad idea." More alarmist authors raised the question of whether taxes risked "killing" mobile money altogether. Notably, however, their broader concern fixated on the total tax burden that is being born by MNOs in some sub-Saharan African countries. Indeed, the thesis contained within the GSMA's warning - that national Treasuries should avoid becoming overly dependent on one sector of the economy for revenues - is a generally sensible one.

But when it comes to mobile money in particular, a recent report from the World Bank concluded that many of the GSMA's specific warnings about the negative effects of the tax regime on the growth of mobile money were misplaced, at least insofar as their case studies of Pakistan and Tanzania were concerned.

The study findings confirm that the taxes levied are relatively small compared to other transaction costs and that their impact on P2P transaction volumes is likely to be minor. As yet, due to the comparative advantage of mobile money P2P transfer services, this applies even when taxes are imposed as turnover taxes (i.e. as a percentage of the transferred principal) rather than as the more usual taxes on fees (excise tax and value added tax (VAT)).

Mobile Money Taxation: Policy Issues and Considerations for Pakistan and Tanzania, World Bank (2016)

Nevertheless, the authors did note that in markets where mobile money deployments had yet to reach scale, the effects of taxes on transactions could be particularly egregious. However, in terms of the relatively sizeable and mature markets under consideration, the study provided three key takeaways for stakeholders:

- Taxation is not likely to influence demand for P2P money transfers.

- Transactional frictions can hamper the way in which mobile money expands beyond P2P.

- Closer coordination among policy-makers is important in moving to enhance the role of mobile money in everyday consumer transactions.

This third point is of particular interest, and one that the report's authors took pains to emphasize: governments need to examine mobile money taxation policies not just in terms of revenue generation, but also as one of the most effective tools in their box for nudging consumers and merchants, and catalyzing the deepening of digital financial services markets. Moreover, closer collaboration and consultation is necessary in order to integrate taxation of mobile money and digital financial services into a broader framework designed to expand the market and enhance the sustainability of such tax revenue streams.

Tax Payment Lubricant

For consumers, mobile money offers solutions to real pain points, particularly in areas of bill and tax payment. A case study from the Better Than Cash Alliance highlighted Tanzania's successful introduction of mobile money as a payment option for a number of government-imposed taxes and fees, starting with the motor vehicle license.

Last year, I started to pay taxes for my motor vehicle using mobile money. Before, I used to go to the tax office, and it would take me one or two days to make the payments. Often the system would be down and I had to go back. I can now make the payments

immediately.”

Madhani Ngao, Tanzania

Within three weeks of launch, over 40% of motor vehicle taxes were being paid via the mobile channel, prompting the government to expand service availability to other tax, license and fee payments. Similar effects were seen in the semi-state and utilities sector, where the introduction of mobile money payments saw a 28% rise in monthly revenues for the Dar es Salaam Water and Sanitation Corporation. In Uganda, between 2012 and 2014, electricity revenue collection rates increased from 94% to over 99%, mainly due to the availability of mobile money.

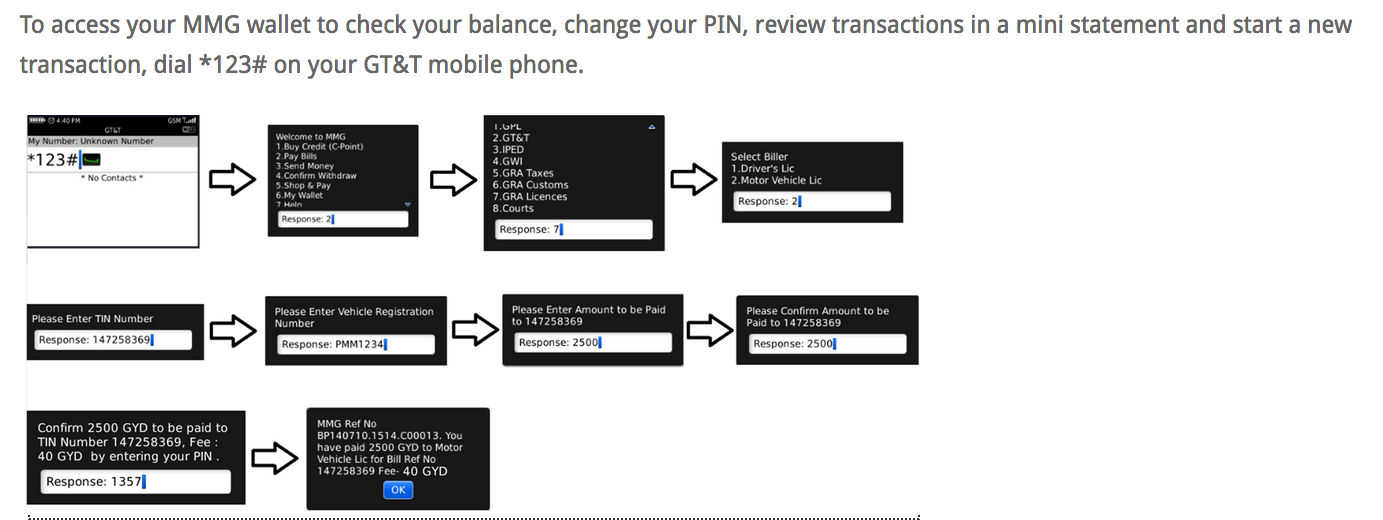

Illustration from the Guyana Revenue Authority on how to pay using mobile money (click to enlarge).

In June 2015, the Tanzanian Revenue Authority's digital payments portal, the Revenue Gateway System, became fully functional, allowing users to initiate a wide-range of P2G payments electronically, including via mobile money. Tax-payers save time and have reliable records of taxes paid, while leakage and fraud are significantly reduced by the electronic payments gateway. Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda are all moving in the same direction, perhaps setting up East African Community members to be at the forefront of a revolutionary digitization of tax payments in developing economies.

Eyes on the Prize

The Bank of Uganda (BOU) is forthright in its positive assessment of the contribution of mobile money to growing tax revenues, and freely admits that within the country inefficiencies can make it difficult for citizens to be tax-compliant in the absence of the mobile payments channel. BOU predicted in 2016 that its newly-launched mobile money tax payment facility would boost tax revenues by some US$25m per month.

Although concerns relating to the privatization of a public good (money) and the de-anonymization of private exchanges (purchases) have been raised, mobile money is a rare beast in that it benefits both consumers and government tax coffers alike, both directly through improved tax collection, but also indirectly through the deepening of the private sector (and even helping to reduce inflation by lowering the velocity of money in the economy).

However, as noted above, taxation policies could be used even more effectively if they are stabilized and form part of a broader digitization strategy, rather than simply viewed through the short-term lens of tax revenue generation. Such a strategic vision will require more comprehensive consultation and collaboration between governments and all public and private stakeholders in the mobile money ecosystem, which is a big ask. But the prize - the massive widening of the tax net and increased tax revenues - is surely one that every developing economy's government ought to keep its eye on and fight for.

Image courtesy of [Images Money](https://flic.kr/p/9VxbfZ).

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Is Paytm The New DFC Poster Child?

Can Digital Finance 'Irrigate' The Water Industry?