The End Of Mobile Money Agent Networks As We Know Them

~9 min read

Walk around Nairobi, and you’ll notice the streets are dotted with green. M-Pesa outlets and agents populate every corner of the city, along with Airtel money agents and the occasional mobile banking agents. While the revolution only started 15 years ago, mobile money is no longer disruptive tech. Agent networks have been the backbone of mobile money growth, enabling its reach beyond cities, across income groups and geographical locations. They facilitated onboarding and mass education to the point where even the Kenyan elderly can operate mobile money systems. And yet, though they’re the face of mobile money for many people, mobile money agents seem to be in jeopardy. With a reduction in income levels and a shift from Cash-In-Cash-Out (CICO) models that traditionally comprised their main source of agent income, their future is uncertain. Where does this shift leave the agent networks? What becomes of them in a world that is slowly moving away from physical cash?

The Plight of the Agents

Agent networks have borne the brunt of price wars among mobile financial service providers. In West Africa, for instance, Senegal’s mobile money ecosystem underwent a shift with the introduction and aggressive marketing of Wave, a mobile money start-up that rattled the market with its 1% fee on mobile money transactions. Senegal’s dominant market player, Orange Money, saw a reduction in users and was pushed to lower their rates from between 5% and 10% to 0.8% of the transactions to remain relevant. While welcomed by users, the fee reduction only reduces agents’ commissions.

In more mature mobile money markets with dominant players, like M-Pesa in Kenya, the agent commissions act as a driving force for the enterprise’s agenda. The clearest example of this is how M-Pesa commission rates for cash deposits are much higher than cash withdrawals. This encourages agents to seek out and support end users to keep more money in their mobile wallets and conduct more transactions (e.g. P2P transfers, paying for goods and services, more withdrawals), all creating revenue points for the enterprise. CICO transactions form the main income source for mobile money agents in the ecosystem.

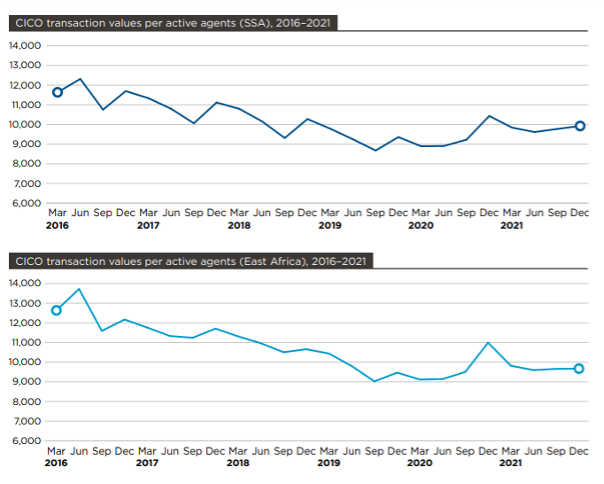

However, these CICO transactions have been reducing over the years, as agents find mobile wallet use cases multiplying and the mobile money ecosystem becomes more self-contained. In Kenya, People using public transport (buses) can pay for their rides through P2P, utilizing the zero-fee transaction cost for smaller transactions under $1. Grocery stores increasingly accept payments through the ‘Buy Goods’ M-Pesa product. All these small changes reduce the need to visit an agent as frequently as one would just a couple of years back.

Source: GSMA

Such a reduction in foot traffic affects mobile money agents’ bottom line, causing them to pursue other revenue sources to complement their income. None of the 12 agents in Kenya that Mondato Insight spoke with rely solely on their mobile money agency as their main business, with side gigs ranging from electronics, phone accessories, groceries, cosmetics, pharmacies, or an amalgamation of mobile banking agencies on top of the mobile money services. These businesses bring foot traffic to their stalls by increasing the number of customers’ needs they serve.

“Most [of the mobile money clients] want to buy something from me. You’ll find them asking for a kilo of beans, withdrawing the payment and a little extra to take home with them. Or they’ll come to buy the beans, see the Mobile Money Agent sign board, and [then] decide to withdraw some cash.”

Joyce Waithera, M-Pesa Agent and Cereal Shop Owner, Kiambu, Kenya

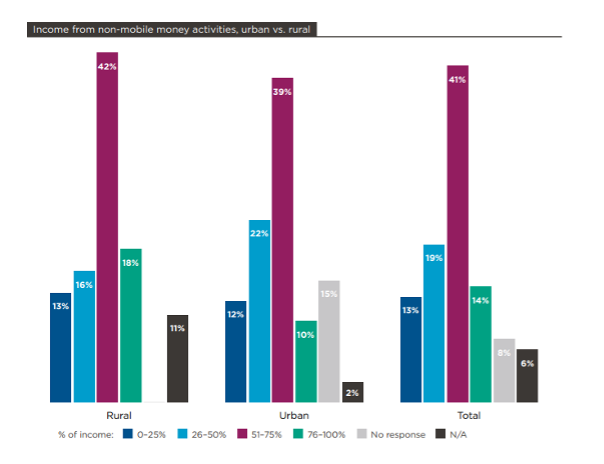

Agents are increasingly relying on these other businesses to compensate for a loss in mobile money revenue. In Kenya, 55% of mobile money agents derive a majority of their income from non-mobile money activities, compared to 32% of agents that receive a majority of their income from mobile money, according to a GSMA report.

Source: GSMA

This trend is expected to worsen if agents’ reliance on CICO continues. While CICO is a critical step to expanding digital financial services to the unbanked population, the market is at a point where it needs to move beyond CICO and towards a more diversified approach to agent networks’ role.

The Gates Are Closed

However, the market remains stubbornly at a standstill as key mobile money players work to maintain their ecosystems by often gatekeeping against interoperability, which increases friction along the value chain. Take, for instance, a housekeeper who is paid via mobile money and must pay her house rent via a local bank. Ideally, she should be able to go to her nearest mobile agent and complete the transaction from mobile money to a bank account — but this would not be possible in Kenya. Instead, she would need to first look for an agent that offers the particular bank’s agency banking services. She would then withdraw the cash from the agent, who would record the withdrawal after confirming it from a mobile phone, and then proceed to make a payment at the POS machine for the bank in question. Even assuming the agent has that particular bank’s POS, this is time-consuming for both parties and makes it hard for agents to transact, as it requires them to have different floats and balance them all out.

It was only in July of this year that mobile money service providers in Kenya were integrated into an interoperable system, which utilizes M-Pesa’s Pay Bill and Business Till features to enable payments for those using other providers (Airtel and Telkom). Yet interoperability is still an issue for agents; finding an agent with more than one mobile phone and several POS systems for mobile banking is not uncommon. Add to this the different record-keeping systems — including requirements to log mobile money transactions by pen and paper, the different float requirements, along with the acquisition and balancing of the different floats, and the added time required to operate inter-provider transfers. It simply becomes a nightmare, according to mobile money agents — and one that agents cannot break out of due to the monopolistic nature of the mobile money space.

Other key markets in Sub-Saharan Africa have raced ahead of Kenya when it comes to facilitating interoperability. In neighboring Uganda, for example, the Uganda Bankers Association began the path to interoperability in 2020, enabling transactions across participating banks on a single system at the agent level. That step alone saw the income of agents, now able to operate between different banks without requiring different floats, to increase. Agents were able to operate more easily within an integrated POS system.

But, left to their own devices, mobile money service providers continue to discourage interoperability. A look at Kenya's mobile money space illuminates the obstacles in sending money between two providers. The first hurdle is in the transaction cost. For out-of-network transactions, M-Pesa charges more than double the cost of an M-Pesa-to-M-Pesa transaction. When it comes to withdrawing that money, the recipient would not be able to withdraw it from their respective agent; they would need to visit an M-Pesa agent, share a code that ascertains they received money, and have the agent conduct the transaction on their behalf. The recipient must do so within seven days of receiving the money, after which the code expires and the money reverts to the sender.

Such high-friction processes discourage people from using inter-provider transfer services. In fact, most agents interviewed in Kenya share that the most likely people to use these services are those trying to bypass unpaid loans to a service provider.

“If they’re sent money to their M-Pesa, their unpaid loan will be deducted, so they receive money via Airtel or T-Kash and come to us to withdraw.”

Ann Wainaina, M-Pesa Agent, Kiambu, Kenya

This gatekeeping further limits the options available for users and encourages CICO models where one simply must withdraw cash sent to them. While it keeps users within a mobile money provider’s ecosystem, it slows down the move toward a cashless society and forces the users to rely on the limited high-cost transaction options.

“The gatekeeping that we see [among mobile money service providers] is short-term thinking, but they need to start thinking about ecosystem building.”

Ali Hussein Kassim, Chairman, Association of Fintechs in Kenya

That gatekeeping has also kept innovation at bay. While M-Pesa was a disruptive innovation at its onset, it has since stalled in innovation, resigned to producing reiterations of its features like different loan facilities, including Fuliza, an Overdraft facility, and M-Shwari, a savings and loans service, to go along with different bill payment systems (Buy Goods vs. Pay Bill) and different apps that provide these services and integrate other payment services revolving around mobile money. This stall in innovation has gone beyond M-Pesa to infect the rest of the local fintech space, which is filled with tech stacks built on top of M-Pesa.

Forcing New Paths

In spite of this ongoing intransigence from industry leaders, a shift in business models for agents is not only necessary, but imminent.

“[Agents] are going to be your agnostic financial services branch. That is the evolution...The business of different agents having different POS’s, five or six of them, will need to be integrated quickly”

Ali Hussein Kassim, Chairman, Association of Fintechs in Kenya

Kassim adds that we will likely see more revenue streams emerge for agent networks beyond payments. Insurance, for instance, provides a vastly untapped opportunity that could be captured through agent networks. Despite being already in existence, agency banking also provides an alternative source of income, one that banks in the local ecosystem have tapped into.

Facing these gatekeeping pressures, mobile money agent networks are undergoing a shift towards them acting as enablers to more sophisticated financial products and services. One of the agents interviewed notes her busiest time is at the beginning of the month when rent is due for many people living in the high-rise apartments around her. She deals with building managers, who refer new tenants to her to facilitate rent payments to local banks.

Yet it isn’t simply new payment corridors that agents are migrating towards, but for them to offer new products altogether. In the B2B and B2C ecommerce spaces, players like Marketforce, a digital commerce marketplace that connects informal merchants with suppliers, could use the agent networks as distribution channels. Marketforce already allows merchants to resell digital financial services such as airtime and bill payments. Marketforce agents also get paid a commission for onboarding retailers onto the platform and for completed orders they collect from the retailers, adding potential revenue streams for agent networks. With a network of about 100,000 merchants in Kenya and Nigeria, the startup already has a supply of potential agents that could sell digital financial services through its platform.

Copia, a retail ecommerce platform, enables purchases of products by middle and low-income people with or without Internet access through its agent network. Through Copia, agents can sign up to help people in their area purchase and access goods, earning a commission from it. With over 30,000 agents across Kenya and Uganda — and even more signing up — its appeal to the agent networks is clear, as locals continue to see an increase in Copia colors — yellow and red — across streets all over Kenya and Uganda, including rural areas. The market will likely see more revenue generation opportunities among agents in the future as new use cases emerge.

But with more revenue streams for agent networks comes the operational challenges of managing the multiple income streams from separate entities, each with their own terms of service. Aggregator platforms like Waynbo by Papersoft are emerging to fill the market gap. Waynbo is a platform that enables agents to access multiple financial services to sell to users, ranging from insurance to utilities payment, retail and banking. It provides a way for partner companies to recruit, onboard and manage agent networks. Such solutions could be key to ensuring better, more integrated systems for agent networks while reducing costs.

Papersoft’s Waynbo has yet to enter the Kenyan market, as it struggles to break through the market’s rampant gatekeeping. Yet the growth of diverse agent network use cases in Kenya may, along with regulatory efforts, may force mobile money operators to facilitate greater interoperability among services.

With these changes, the role of the mobile money agent goes beyond representing a few mobile money service providers. As innovative solutions providers like Copia and Marketforce slowly turn agent networks into their distribution networks, the ability of mobile money agents to educate the masses and provide last mile connection for companies will increase their relevance over time as they take on more revenue-generating income streams beyond payments and transaction facilitation. Through such changes, mobile money agents aren’t left behind in Africa’s progression beyond simple payments and more sophisticated financial services — they are pivotal players in facilitating the ecosystem’s evolution and development.

Likewise, the push towards interoperability and zero-cost transactions will force mobile money service providers to go beyond CICO models of revenue generation. Consequently, we may finally start to see more innovation on their end — or witness a reduction in the green storefronts blanketing Nairobi and other cities in Kenya, as agent networks strive to survive by diversifying beyond mobile money.

Image courtesy of M-Pesa

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Gambling And Fintech: Two Sides Of The Same Coin?

Brazil’s Pix: Should Instant Payment Rails Be A Public Good?