We Need All Three: How ID, Finance, And Mobile Can Help The Poor

~11 min read

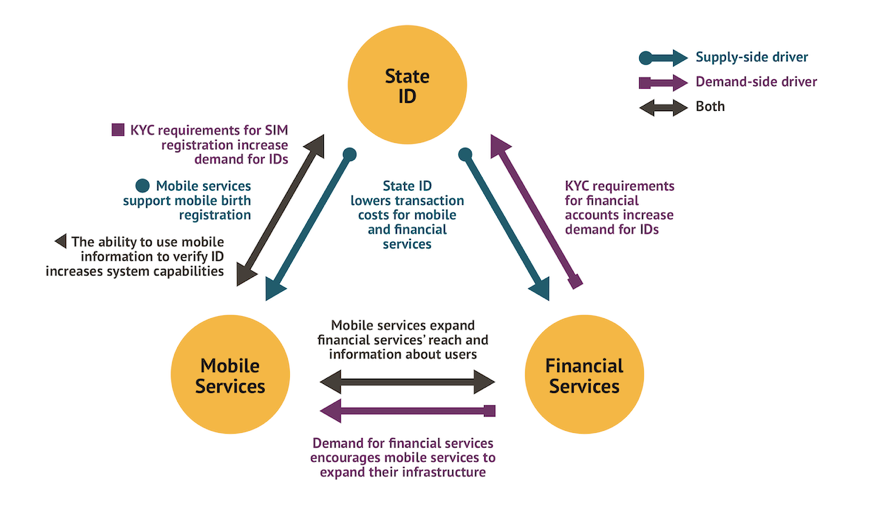

In development circles, there’s the popular notion that in order to improve economic and social inequities among the poor and marginalized in developing countries, a “trinity” of characteristics must be attained: mobile connectivity, access to the financial system, and possession of a digital ID. These three components in theory have a synergistic relationship with each other, leading to better conditions for the underserved. But a closer look at each of these three and their interdependencies reveals a more complex picture, where other factors like adoption, local considerations, and market forces can make or break even the best-intentioned initiatives.

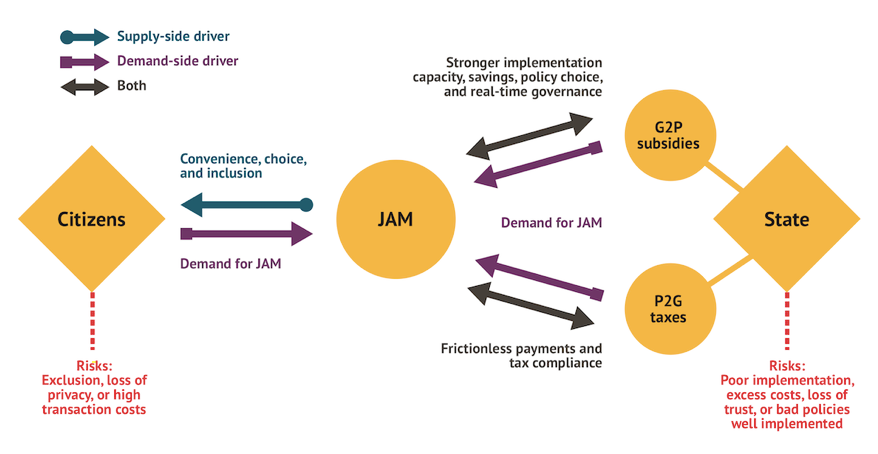

The concept is most directly exhibited in the case of India and its government’s JAM trinity, short for Jan Dhan accounts, the Aadhaar system providing biometric IDs to all of India’s citizens, and Mobile connectivity. The JAM trinity endeavor has provided financial accounts to over 350 million Indians previously excluded from the financial system. These accounts, linked to Indians’ mobile phones verified by their Aadhaar digital ID, have become the conduit for the government’s vast subsidy system. Although India’s case is the most direct example of this digital trinity in action — leading accompanying literature to label digital trinities elsewhere the “JAM model” — variations of the concept are being implemented in countries around the world. But whether looking at cases ranging from South Asia to South America, simply employing this “JAM model” is insufficient to enacting real change if it ignores local conditions and a state’s pre-existing digital capacity and knowhow — or if the quality of its separate components is lacking. Potential issues like digital literacy and market incentives on the supply and demand side must be properly remedied in order for the concept to reach its full potential. The digital trinity, or JAM model, is not the end all be all of digitally-oriented development initiatives — it is simply the foundation upon which governments must adapt to pre-existing strengths and weaknesses in order to effect ambitious behavioral changes.

More Than The Sum Of Their Parts

It’s difficult to describe the benefits of the JAM trinity’s three components as standalone entities. The first component, mobile connectivity, has served as the bedrock for much of the fintech revolution creating digital financial ecosystems in developing countries. Vast mobile ownership in developing countries has produced the right conditions for innovative solutions like mobile money to be adopted by the previously financially excluded. Sub-Saharan Africa of course is the leading example, as people switched to mobile money services like Kenya’s famed M-Pesa due to a lack of formal banking in rural areas and rampant cash theft. By providing the means for poor and rural populations to access financial services like savings, credit, and even more sophisticated tools like insurance for the first time, the results have been at times stunning. Studies have suggested that Kenya’s M-Pesa revolution managed to lift 2% of Kenyan households out of poverty, increasing the financial resilience and savings capabilities of the country’s poor.

Source: Center for Global Development

The advent of digital identity has proven to be a vital resource in making such progress happen. Lack of proper documentation necessary to satisfy Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations has often made it impossible for the marginalized to participate in the financial system, and analog ID systems are inefficient and vulnerable to corruption and fraud. Digital identity, a broad concept encompassing biometric data but also digitized biographic or personal data, helps marginalized groups overcome these identity barriers to the financial system. India’s Aadhaar program, which created biometric IDs for over a billion Indians, managed to reduce the costs of KYC efforts per user in India from $15 to $.50, improving the conditions for financial service providers to target hard-to-reach populations. A McKinsey report estimated that digital ID could increase access to digital financial services for more than one billion financially excluded individuals across the world.

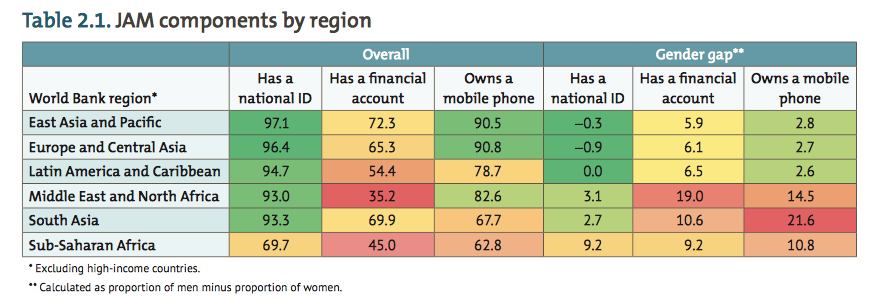

An exhaustive report by the Center for Global Development (CGD) published in late March looks further into how these three factors actually interact with one another to produce government reforms and initiatives to improve people’s lives. CGD found that owning a mobile phone emerges as the most important contributor to bridging (or widening without such attributes) the gender gap in financial inclusion followed by having a national ID, with exaggerated effects among low-income countries. Globally, when socioeconomic conditions are favorable, CGD estimated the probability that an individual will have a financial account is as high as 84%, and when condition are not favorable, financial inclusion drops to only about 7%. But having an ID and a mobile device boosts the probability of financial inclusion to 34% for that same demographic. While cash transfers have no positive impact on financial inclusion, receiving a digital transfer boosts the probability of financial inclusion by 31%.

The digitization of government-to-person (G2P) transfers — which all but requires a state-mandated digital ID, a mobile phone for remote transfers, and accounts to receive and utilize such transfers — has been the greatest means by which underserved populations have been included. In the CGD report’s 99-country sample, 44% of people in low-income countries who had received a government transfer reported that the first account that they opened was to receive this transfer. The effect was stronger in lower middle-income countries where transfer payments were more frequently made though financial accounts rather than cash.

Source: Center for Global Development

This G2P-led model of the JAM trinity manifests most clearly in India’s digital transformation of its vast subsidy programs. India’s fuel subsidies system was long rife with corruption and inefficiency, and in 2014, only about half of India’s households had access to clean LPG cooking gas. The subsidy, disproportionately going towards higher-income and urban groups, was billions of dollars more expensive than necessary, and vast amounts were diverted to the black market. The PAHAL program reformed the system to deliver the subsidy directly into civilians’ Jan Dhan accounts as a voucher. Customers could track their deliveries, rate their distributors, and change them if dissatisfied. The program removed some 25 million false and inactive recipients, and dealers could no longer divert the subsidies. The carryover effects were significant. Finally obtaining the full subsidy owed, wait times decreased and millions of households switched away from the use of harmful biomass fuels, which accounted for nearly 500,000 deaths per year in India.

That the Indian government could now effectively target populations and fully deliver benefits greatly expanded the government’s capacity to enact intersectional social change. India’s Ujjwala program provides qualifying rural households with a 50% subsidy to purchase a gas connection and stove — but only women in households are eligible, and the program requires them to sign up for a bank account. So far, approximately 75 million women have benefitted. A randomized control trial of different Indian social benefit programs found that when women received payments directly into their own accounts and were trained on how to use them, they worked more and earned more, and their husbands were more comfortable with their wives working outside the home.

By centralizing and digitizing subsidy distribution, a JAM model also creates the ability — though subject to capacity and design — for real-time response mechanisms. In India, government officials in 640 Indian districts receive daily progress reports on PAHAL, allowing for tweaks to the system and effective response mechanisms to issues and complaints. With such supporting infrastructure, a digitized system can foment the trust and repeat usage necessary to effect behavioral change towards digital means.

Down To Earth

The JAM model has enabled digitized G2P payments — and thus greater levels of financial inclusion — in other countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Kenya and Togo. But two critical questions remain: what people actually do with these tools suddenly at the disposal, and how effectively the systems are designed and implemented.

On the first question, digitized G2P initiatives have done wonders in expanding financial accounts to the underserved, but digital finance professionals are still often flummoxed over how to create the proper incentives and market conditions for financial behavior to change in broader terms. The CGD report described how in Bangladesh, the government moved to transfer stipends for nearly 13 million children directly to mobile banking accounts for their nearly 10 million mothers. The program had substantial effects on the financial inclusion of these mothers, only 31% of whom had any other mobile money account. But 90% of the recipients only used the accounts to cash out these stipends. Without an interoperable and robust digital ecosystem catering to their needs, the impact of this successful-on-paper initiative was limited in real terms.

“With digital identity, mobile phones and access to mobile money, people are able to send and receive money with a few clicks on their phones and they’re able to receive money from governments. But after that, it kind of plateaued. If you look at digital financial inclusion, digital payments account for most of the digital transactions. Other tools such as savings or insurance or even online lending haven’t really taken off. So I think that JAM has made great progress, but it’s not time to rest on its laurels.”

Audrey Misquith, Digital Financial Services Professional, Asia

Anit Mukherjee, one of the authors of the CGD report who also helped design the Aadhaar system for the Indian government, points out that following India’s demonetization initiative several years ago, many reverted back to old habits once the cash crunch eased. Simply forcing people to use digitized systems didn’t assuage lingering trust concerns and preference for cash among heard-to-reach segments like rural and older civilians. When looking at the JAM system as a whole, the model’s impact on financial inclusion when factoring mobile connectivity and digital identity still falls short of its potential. The CGD report gave dozens of countries a so-called “JAM score” out of 300 points, with countries scored from 0 to 100 based on the three respective categories. What was most striking was how they consistently found countries’ scores in digital identity and mobile connectivity to be well above their financial inclusion score.

Source: Center for Global Development

The JAM-like model implemented in Peru serves as one notable example of results falling short of conceptual promise. Peru linked its digital ID to a new service known as BiM, launched in February 2016, which provides services such as cash in/cash out at agents, the ability to check balances, conduct P2P payments and top-up airtime credit. Though high mobile ownership rates and widespread digital identity possession would suggest the conditions for increased financial inclusion, adoption of the mobile money service has been slow. Unlike the JAM system in India targeting the inefficient subsidies system, the BiM system has lacked the same incentives for adoption. A consortium-based system comprised of dozens of mobile money providers, Peru’s system allows for interoperability, but it failed to correctly align the development objectives with the financial interests of mobile money providers, discouraging expansion to marginalized groups, and it failed to adequately protect against cases of cyber theft, which damaged the program’s ability to build trust.

This gets to core issues any JAM model must address in order to be successful: reforming and improving underlying infrastructure to ensure high quality in the three components, and for the design of the system to be responsive to the needs and characteristics of the given population. In India, the top-down approach to the JAM model meant that significant resources were devoted to guaranteeing the program’s success. But implementation at the state level elicited varying results depending on the state government’s capacity and approach. The CGD report compares the implementation of the digitized public distribution system (PDS) in three different states: Jharkhand, Rajasthan, and Andhra Pradesh. Compared to Andhra Pradesh, which possesses a more digitally savvy population and government, Jharkhand is poorer, with less digital capacity and knowhow in its government. The digitized PDS reforms in Jharkhand focused primarily on saving public resources; unlike in Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh, there was no effort to widen the low dealer margins to compensate for the effect of tightening controls on dealers’ ability to divert rations to the market. By failing to account for this, the market failed to transition properly as corruption continued. The state also faced issues in biometric authentication, and there weren’t proper response mechanisms put in place to address such issues, leading to instances of greater exclusion from the Aadhaar-based system, not less. Without a clear vision for benefits to civilians or appropriate design and risk-based response mechanisms, the digitized system failed to deliver the results found in Andhra Pradesh, whose government took a beneficiary-centered approach to reforms.

The Jharhkand case is one where linking digital ID to financial or social services actually excluded those who still don’t possess an ID. In this sense, when infused with a discriminatory agenda, digital identity reforms can be disastrous for marginalized groups. In Kenya — renowned for its mobile money-led inclusion efforts and noted by CGD for its high JAM score of 258 — controversy ensued when the government sought to implement its own digital identity initiative last year. In order to obtain a digital ID, the scheme requires a proof of identity, with a discriminatory vetting system for marginalized groups in the country. The government’s own data revealed 10% of applicants were turned away for lack of documents — creating a chicken and egg conundrum for the already excluded. Mukherjee stressed the importance of designing such digital identity initiatives as a functional ID, as was the case in India, and not a national ID.

Pre-Existing Conditions

Even under the best-designed JAM model programs, however, marginalized groups need to actually be ready and able to adopt these tools. Low digital and financial literacy for women in places like Pakistan and Bangladesh are barriers for the systemic progress JAM-led programs seek. Such barriers can’t be remedied with JAM alone; supporting infrastructure and training programs are necessary. At the micro level, there may be issues like in South Asia where a woman’s digital identity — and the benefits connected to it — are often linked to the family’s sole mobile phone, which is controlled by the patriarch. These local characteristics have to be addressed to reap the intended results.

The best JAM model is one responsive to the natural strengths and weaknesses of a country’s three components. India’s JAM model, building on and reforming its legacy subsidy systems, is driven by its Aadhaar system and ubiquitous mobile use. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where mobile money rules the roost, the private sector-led efforts of companies like M-Pesa fundamentally impacts how its JAM comes to shape, with its identity aspects still catching up.

“Any digital system is built off an analog base system. I live in a 100-year-old house. If I put another story up there, I would be scared it would fall. It’s the same idea. If you simply move [populations] to a digital system, nothing changes. You replicate barriers and maybe make it worse by increasing surveillance. But if you are designing digital systems to take into account the problems you see in the base system, then you are moving towards a better system.”

Anit Mukherjee, Policy Fellow, Center for Global Development

As the disparity in CGD’s JAM scores between mobile ownership/ digital identity and financial inclusion makes clear, these changes will not come overnight, even with a focused vision, proper design corresponding to local conditions, and sufficient resources and political will. But as one of the co-architects for one of the most successful examples in India, Mukherjee views this disparity as a mere snapshot of the early stages of the burgeoning digital financial revolution. Dramatic behavioral change takes time and requires a careful realigning of market incentives with consumer need. Since COVID-19 hit, countries like Togo and Bangladesh have unexpectedly stepped up to employ a JAM-like model to deliver social benefits remotely, as people who may not have seen much use for these tools previously now find it a critical asset in these unprecedented circumstances. It’s opportunity finally aligning with capacity.

The path to reaching JAM’s desired ends won’t look the same in two different places, and it certainly won’t require the same time and resources. Any JAM model without the proper political will, resources, response mechanisms, complementary development initiatives and synchronization of supply and demand features of the given market will fall short of its promise. But in spite of its hurdles and risks, the JAM model will undergird any country’s efforts to bring positive intersectional change for its poor and marginalized groups through digital means.

Image courtesy of Annie Spratt

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Central Africa's Path Forward: Regional Digital Cooperation

Telehealth Is The Next Digital Opportunity