Let Us Not Forget: The Internet Is A Human Right

~6 min read

The United Nations has officially considered the internet to be a human right since 2016. According to The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we must recognize “the global and open nature of the Internet as a driving force in accelerating progress towards development in its various forms.” From a certain perspective, the internet and access thereto have become democratized, with an estimated 53.6% of the world’s population online as of 2019 - about twice as many as ten years prior. Meanwhile, the internet as a channel for the delivery of financial services - like payments, banking, credit, advisory, and insurance - has also grown, and by some measures at a faster rate still. But as the internet and its potential to create inclusion have grown, institutions haven’t treated access as a right, and even in developed countries, citizens are seeing their online rights curtailed. If the internet is indeed a human right, when will governments begin to treat it as such? And what does the current restrictive behavior of many world governments imply for the world’s newly-online?

Can't Live Without It

There are many reasons to consider the internet a fundamental human right. Firstly, it is a uniquely democratic medium, according to Dr. Merten Reglitz, Lecturer in Global Ethics at the University of Birmingham. The internet gives individuals the ability to both send and receive information, and to participate in organized efforts to influence institutions. Second, the internet has permeated society to the point that the rights to free expression and assembly cannot be fully exercised by citizens who aren’t online. Insofar as political participation is productive for underserved populations, a lack of internet access can keep individuals from adequately expressing their point of view or organizing for a cause. And finally, the internet can act as a safeguard for other human rights; wherever individuals can use the internet to hold institutions accountable (whether by providing direct evidence of malfeasance or organizing for collective action), other fundamental rights like life, liberty and bodily integrity are thereby upheld. For Dr. Reglitz, the internet is a human right precisely because we’ve made it such a central pillar of modern life:

"The upshot of these considerations is that we have weighty reasons to accept the idea that free Internet access should be considered a human right because it is necessary for ensuring minimal decent lives in the digital age. The current and potential benefits of such universal Internet access are important enough to create a moral obligation for states and the international community to create laws to ensure that everyone can ‘go online’."

Dr. Merten Reglitz, Lecturer in Global Ethics, University of Birmingham

With so many aspects of life (including, increasingly, financial services) now mediated via an internet connection, to lack such a connection excludes individuals from services that might improve both their immediate circumstances and future potential for prosperity. The digital financial services industry is home to multiple examples - from payments to savings to credit and more - of internet-enabled services which improve outcomes for underserved populations, and it is rare for any ambitious endeavor in the sector to neglect to mention the world’s 1.7 billion unbanked. However, the COVID-19 pandemic also forced healthcare, education, and government services online, making the internet the only channel for some of society’s most essential functions. Without network access, individuals are at risk of being left untreated, uneducated, and unassisted as well as unbanked - making the internet (and all associated preconditions to full, free access to the internet) a must-have for any inclusive society.

Free Is Fair

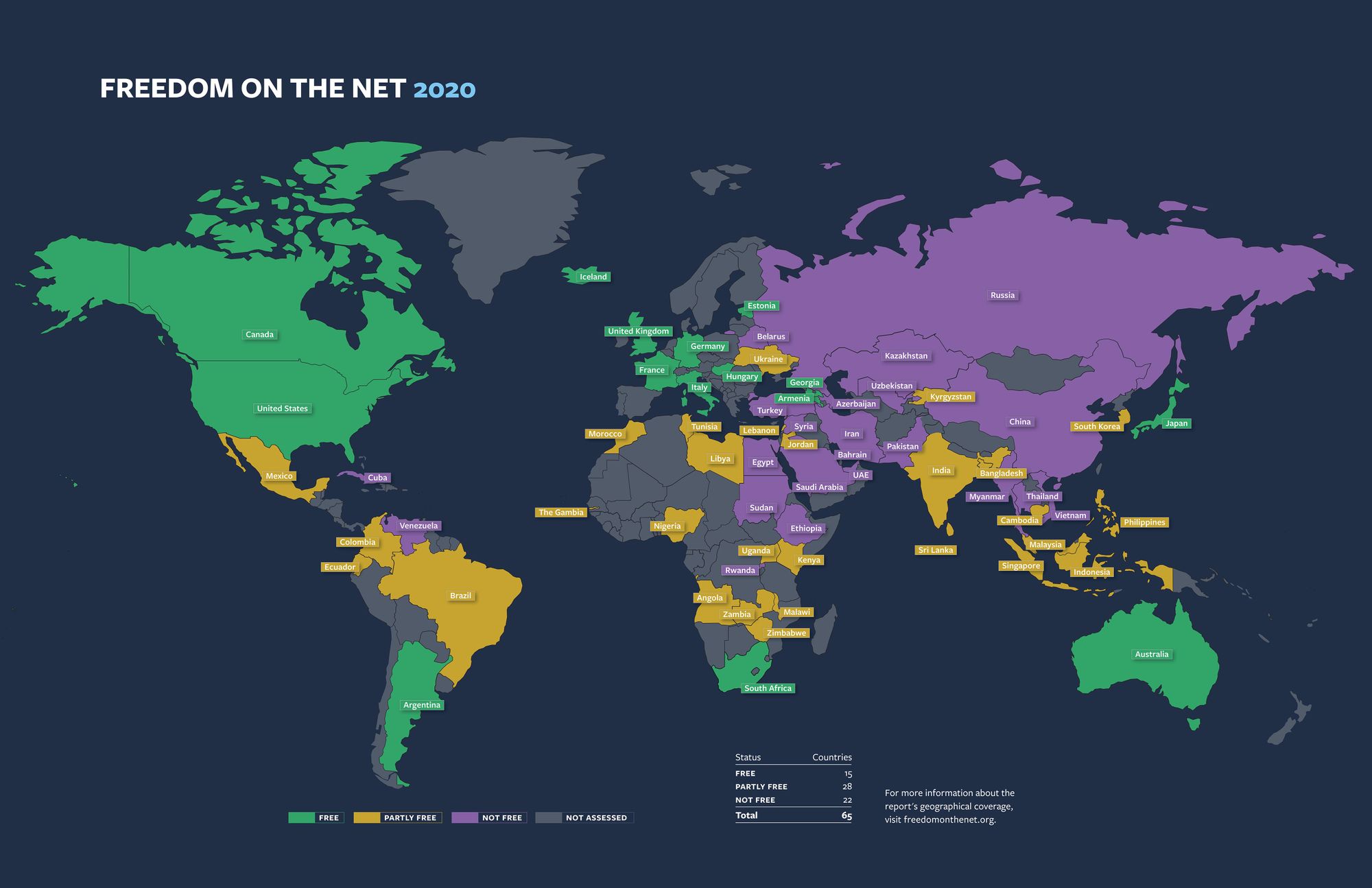

As the pandemic has persisted and societies across the world have come to rely on the internet to a greater degree, the internet has concurrently become less free. Freedom House, a non-profit that has been studying freedom online for 10+ years, noted in their 2020 report that the COVID-19 pandemic “is accelerating a dramatic decline in global internet freedom”. The report tracks obstacles to access, limits on content, and violations of user rights to measure and compare internet freedom in 60+ countries.

When a country’s government interferes with internet freedoms, Freedom House tracks the incident and accounts for it in the country’s score. So when 22 governments (including those of large nations like China, India, Russia, Ethiopia, and Indonesia) deliberately disrupted ICT networks within their respective borders this year, those countries were observed to be less free, as deliberate disruptions are not considered to be a feature of free and fair internet management at the country level. Likewise, Freedom House observed various cases of overreach by governments in response to (or under the pretext of) the pandemic, and noted these cases as detrimental to freedom for the countries in question. In Egypt, for example, the Supreme Council for Media Regulation barred several opposition news outlets online after accusing them of spreading false information. And in Bangladesh, the government took down a news site where leaked information had been shared which illuminated the country’s rising case numbers. Each such incident constitutes a loss of freedom for the citizens in a given country, and taken in aggregate, they paint a picture of a global internet that is less free, less fair, and under ever-stricter institutional control.

More specifically, Freedom House found that in 2020, the web is either “Not Free” or “Partly Free” for 67% of the world’s internet users, with only 20% of users living in “Free” internet countries (and 13% falling outside the study’s remit). These figures represent a 3-4% global shift relative to the same group’s findings from 2016, when 64% of the world’s internet users were “Not/Partly Free” and 24% were “Free”.

Source: Freedom House

If the 2016-2020 period has indeed brought a swing toward less free internet access for the world’s citizens, then it has coincided with a period of steady growth in the number of global users. ITU estimates suggest that from 2016 through 2019, 3% of the world’s population (or roughly 225 million individuals) became internet users each year. If this growth rate can be sustained, then individuals in the world’s least-developed countries would likely see considerable gains in access, as the regions of Africa, Asia Pacific, and Arab States (at 28.2%, 48.4%, and 51.6% internet penetration, respectively) lag behind the global average. However, governments in many of these regions are not in favor of a free and open internet, and the persistent gender gap observed in internet penetration in many regions is a burdensome impediment in its own right.

On The Right Side

While internet freedoms have eroded over the past handful of years, that does not necessarily indicate that this trend will continue. As institutions have taken increasingly concerning steps, activists have in turn rallied around causes like net neutrality, online privacy and encryption, and censorship. Institutions are not immune to such pressure. In Belarus, when the government imposed a nationwide shutdown of mobile and internet services amid the country’s controversial presidential election, protests in the capital of Minsk intensified, straining relations between the ruling Lukashenko administration and Moscow.

Meanwhile, in the private sector, tech giants Facebook and Twitter have faced fierce criticism from across the political spectrum in response to their handling of so-called “fake news” as the presidential election approaches. In response, U.S. lawmakers are taking a close look at Section 230 of the communications act, which grants online platforms immunity from liability for content published by users. If section 230 were to be repealed or reinterpreted (as President Trump has called for), tech companies might lose the legal grounds to censor content on their platforms.

However, as Dr. Reglitz argues, there are reasonable and necessary restrictions on online activity. Absolute, unregulated online freedom is neither realistic nor desirable. He notes, however, that a distinction must be drawn between internet use and access:

"Few rights are absolute and the right to access and use the Internet is no exception… Cyber-bullying, the spreading of false (‘fake’) news, the use of social bots to manipulate voters, and the mass surveillance on the online activities of unsuspicious citizens - even by democratic states, all call for regulation. The precise legal nature of these restrictions are yet to be determined, yet the harms of current Internet use do not undermine the arguments for access."

Dr. Merten Reglitz, Lecturer in Global Ethics, University of Birmingham

Restrictions on internet use, in other words, should have no bearing on our collective need for universal, free internet access. Just as there are restrictions (e.g., anti-money laundering measures) on financial activities which should not interfere with individuals’ right to access financial services, so should restrictions on what citizens do and say online not interfere with the right to be online in the first place.

A free, widely-accessible internet is increasingly essential to living an included, prosperous life, and as more and more essential services go online, we must ensure that the channel via which these services are delivered does not itself become overly restricted - or worse yet, an instrument of control. For every community that may benefit from digital services - whether they be financial, healthcare, education, or of another type - a single human right first undergirds the provisioning of these services. To fully deliver on the promise of inclusion, the internet must be on the side of the people who need it, with as few restrictions and as much accessibility as can responsibly be managed.

Image courtesy of Engin Akyurt

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Price To Win: How Pricing Can Set A Fintech Apart

Central Africa's Path Forward: Regional Digital Cooperation