Good Deals, Better Data: Cash-Back's Big Comeback

~7 min read

This July, Japanese multinational Rakuten quietly closed its United States based e-commerce platform. Formerly known as Buy.com, the platform was a 2010 acquisition by Rakuten, who were aiming to compete with Amazon for a share of the American e-commerce market. Over the long run, the business failed to keep up with Amazon’s astonishing growth. But Buy.com was just one of several acquisitions by Rakuten over the last decade, as the company has grown an alternative e-commerce empire supported by data analytics and digital marketing (as opposed to Amazon’s iron grasp on optimized selling and fulfillment services). Rakuten’s diverse businesses work in tandem, offering digital consumer services that generate data, which Rakuten then packages and sells back to other brands and marketing agencies. While some of its businesses like Rakuten Rewards (the survivor of the e-commerce platform closure) may seem innovative to new users and vendors alike, it tracks as a digital upgrade to the historical marketing tactic of mail-in-rebates--including some of the same benefits and drawbacks for consumers (though at greater scale). Given the newfound popularity of similar services like Honey (itself acquired by PayPal in 2019), digital cashback services may be the newest piece of the digital commerce puzzle -- with strong revenue and growth models to back it up.

A Not-Quite Comeback

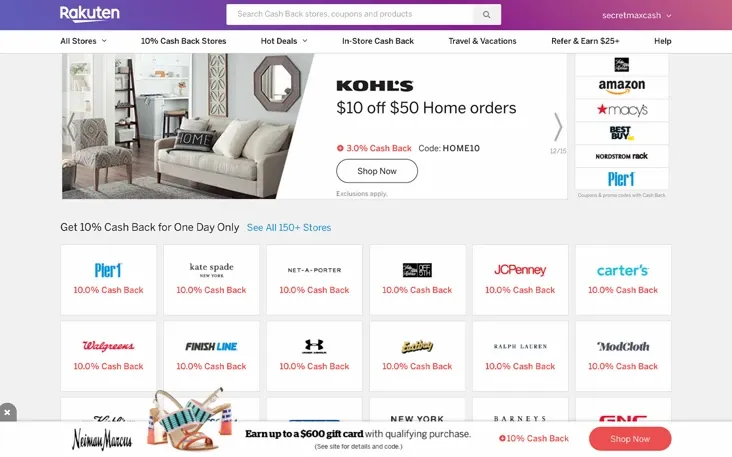

Rakuten Rewards is a rebranded version of eBates, a digital rewards company that was acquired by Rakuten in 2014. Rakuten Rewards draws customers and virtual stores together by offering cashback and coupon deals. When users click on a deal on Rakuten’s website or mobile app, they are brought to the vendor’s website via a Rakuten portal that presents them with available deals as they shop. This service is also available as a downloadable browser extension. For every sale made through a portal, Rakuten earns a commission from the vendor.

There are several brands offering a similar service as Rakuten Rewards to online customers. Many of these brands are housed at fintech companies, like Capital One’s Wikibuy and PayPal’s Honey. The companies offer consumers deals while also earning sales commissions and gaining access to a new set of consumer data that can be used in-house or packaged and sold to other businesses. It’s no surprise that fintechs have entered into this space, as the business models resemble those of payfacs--earning a cut of every transaction that they facilitate. And the business model is lucrative. Last year, Rakuten Rewards earned a commission of transactions totaling $14 billion worth of sales.

Source: Rakuten Rewards

At the same time, the business model is reminiscent of the mail-in-rebates clearing houses of decades past. These advertising agencies managed rebate offerings and processing for brands across the spectrum of consumer goods, from health care products to household appliances. Rebates enabled brands to list the lower, rebate-included prices on products. Customers frequently chose the seemingly lower-priced product over in-store alternatives, but most of these customers never mailed in their receipts to receive the rebate that drove their price-based decisions.

Although rebates have been a popular marketing tool over time, they have gone in and out of style as the tides of public opinion have fluctuated. Companies have also found rebate pricing strategies can lead to brand cheapening, in addition to being a hassle to manage. On the other hand, consumer advocacy groups have railed against rebates as misleading because of the intentionally tedious process to redeem them. And by the 2000s, concern grew over data privacy as consumers were increasingly asked to supply personal information in order to redeem their rebate.

As early as the 1980s, industries and consumers alike faced their first bout of rebate fatigue. Surveys cited by the New York Times in 1988 showed that while customers said rebate offers influenced their product selection, they also said the process for obtaining the rebate was discouraging. Industry reports from the time showed that fewer than 10% of eligible rebates were actually redeemed by customers. Nevertheless, marketers have never quite thrown rebates away for good because, well, they work. Consumers throughout the decades have shown preference for products offering rebates and, as a group, also consistently fail to reclaim the advertised savings.

Manufacturers traditionally contracted rebate clearinghouses to manage the processing and payouts of rebates. By the mid 2010s, tech companies like Rakuten Rewards and others began to disrupt and digitize the business of rebates, replacing the old paper-based businesses.

Digital Makes The Difference

In the case of these new digital-first companies, the rebate model has flipped. In the past, customers went to a physical store and compared prices among the available products, and might have been swayed by the rebate price. Now, customers begin their search online with the third party discount service. The third party presents the customer with deals and portals to shop them. The company receives a commission from the vendor when customers ultimately make a purchase that they split with the customer in the form of “cashback.”

While the sales process has flipped, the same consumer concerns persist. As in decades past with mail-in-rebates, the digital alternatives make users wait to receive their cash. Some places like Honey payout once users meet a threshold amount in cash back, while others like Rakuten payout on a quarterly basis (in addition to having minimums). These limitations and virtual hoops are reminiscent of the multistep mail-in-rebate process.. For example, Honey Gold is a browser extension that presents users with cash back opportunities as they shop online. Consider a Honey Gold user who has been shopping and earning on average 2% cash back on her purchases. She would have to spend $500 dollars before she is eligible to redeem her points for a $10 gift card from a set selection of brands. In the case of Rakuten, the user only has to earn $5 worth of cash back to redeem, but she’ll only receive it at the end of the quarter. If the user hasn’t met the threshold by the end of the quarter, the earnings are rolled over to the next quarter. On either of these payment schedules, users are likely waiting even longer than the eight to ten weeks their mail-in-rebate predecessors waited to receive their promised shopping discounts. From the consumer's perspective, the game hasn't changed much between the days of mail-in-rebates and these online deal-shopping services.

To understand how much money might be on the table for the consumer, consider individual spending data from Amazon. According to Statista, Amazon Prime members spent an average of $1,400 each year between 2014 and 2019 compared with an average of $600 by non-members. If a user were earning 2% cash back on all her Amazon purchases via a third party, she could be earning around $28 on the higher end. Using Honey, she would only receive two $10 gift cards for the year, leaving out $8 (which would roll over to the next year). Using Rakuten, she would be eligible to receive between $25 and $28 depending on when she shopped with respect to the quarters.

High thresholds and delayed payouts mean many shoppers won’t see the benefits of using these browser extensions immediately, even though the extensions present checkout totals with the coupon codes and cash back deals already applied. While users may eventually receive their cash back, it's not as straightforward a scheme as many consumers might think when confronted with a shopping cart total including cash back discounts. The perceived price influencing consumer behavior is not the actual price they will pay. Consumer advocacy groups as fas back as the 1980s had the same observation regarding the ethics of price listings with rebates applied, when businesses knew that most of their customers would not ultimately pay the discounted price.

The Not-Quite Comeback

While consumers are still getting the same bargain they did before, operations have changed radically for the companies offering e-commerce deals. First, the deals business is potentially far more lucrative than mail-in-rebates ever were because transactions are happening at scale. Second, and perhaps most importanly, they are now essentially data businesses. For example, Rakuten Rewards generates data that helps fuel other Rakuten companies conducting analytics at the frontiers of digital marketing and brand management.

“We sit at the intersection of brand and performance advertising. By pairing deep and robust views of consumer shopping behavior and intent with our ecommerce and cash back capabilities, we can drive efficiency and effectiveness of spend for brands in nearly any vertical. Through our media businesses like Viki and Viber, merchants can get the reach and engagement of a large media entity. But we can also do something most media brands can’t – Influence purchases and drive conversion.”

Rakuten Rewards President Kristen Gall

The innovation for the field lies in the two-sided business model. One is consumer facing and offers an e-commerce service like cash back or email sorting. The data gathered from this side of the business is the raw material for the business-facing side, which generates unique insights on consumer behavior for other brands and advertising agencies. For companies like Rakuten, there are even more than two sides. Some other company acquisitions like unroll.me and Slice are also consumer services that feed into its larger data business. Unroll.me, for example, is a service that unsubscribes users from junk mail while highlighting order shipping updates. In order to gain access to the service, consumers give complete access to their email accounts to Rakuten. Rakuten then monitors its users’ emails and compiles data relevant for manufacturers and retailers. Slice is a similar service that searches email accounts for purchase and shipping updates and tracks them for the customer, but also compiles data.

While data privacy isn't a new issue when it comes to the rebate business, the scale of data being tracked is. Consumers may also be less aware of what and how much data they are signing over to these e-commerce companies in the search for a good deal for an everyday purchase. Rather than simply filling in a name and address on a rebate form, consumers are effortlessly sharing their broswing data and shopping habits. When consumer data is worth so much, perhaps consumers ought to be asking for more than 2% cash back from the companies that are profiting.

Nevertheless, e-commerce companies with consumer-facing sides are highly valuable for the brands they serve on the business-facing side. Their membership deals drive sales and customer conversion, while their data insights enable other businesses to more efficiently tailor their marketing. The cost may come down the road if Rakuten and similar companies end up in the middle of a debate about how consumer data is monetized and who gets what share of the profits. In the meantime, retailers may feel compelled to partner with a cashback provider to drive new customers to their site and more sales. When potential customers compare products on the internet, they are more likely to go with the product and vendor that offers the best deal, even the actual benefits of the deal are small and delayed. Consumers are getting value when they shop with these sites, but all signs point to businesses getting an even better deal than that.

Image courtesy of George Pagan

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

What The 2020 U.S. Election Could Mean For Digital Finance

Investing In Latin America: The New Global Fixation