Do 'Cash Machines' Have A Future Without Cash?

~6 min read

If we ever, indeed, do arrive at a global cashless future, historians may some day trace its birth to Enfield, a suburb in north London, in the summer of 1967. It was here that Barclays Bank, working with the De La Rue company, inaugurated the world's very first "cash machine", as the plaque above the spot now commemorates, ultimately making life easier for hundreds of millions of people.

The world’s first cash machine was installed here on 27 June 1967. Lives made much easier.

Plaque outside the Barclays bank branch in Enfield, North London

Although technically not the world's first ATM (earlier in the decade in New York a six-month trial of a machine that accepted cash deposits was tested), the world's first automatic cash dispenser created a paradigm shift in customers' expectations of being able to access their money outside the fairly restrictive opening hours of a bank.

It was not all digital high-tech at the beginning, though. This initial iteration worked without the mag-stripe technology that would go on to become the backbone of the world's debit and ATM networks: customers had to obtain £10 "vouchers" in the branch that they could then redeem at the machine within 6-months for the equivalent amount of cash. But within a short period of time, the relative ease with which customers could "cash out" of their bank accounts created incentives for payments, particularly salaries, to be "cashed-in" directly into accounts, creating the virtuous circle of available funds and ubiquitous access that has so far still evaded most mobile money deployments, and indeed most of the 'X-Pay' NFC-based mobile payment initiatives.

And once bank customers were carrying bank cards that accessed current accounts, it was but a small step to widespread debit card acceptance, 'X-Pay' mobile phones and watches, and perhaps in the future a wide variety of form factors with embedded NFC capabilities. But this being so, where does it leave the humble ATM?

ATM versus Cash Machine

Part of the answer lies in the tale of two cities that marked the birth of the ATM/cash machine, and the differing transatlantic nomenclature that surrounds them. The City Bank of New York's 1961 "Bankograph" (a name that surely needed more workshopping) accepted deposits and was mostly known as a favorite of gamblers, pimps and prostitutes who preferred to avoid face-to-face interactions with bank tellers (a factor that cannot have added to the allure of being seen using the machine), but did not dispense money, factors that combined to make the trial a failure.

Although Barclays "money machine" (which beat a Swedish savings bank and Metior's launch of the "Bankomat" by barely a week) quickly became known by its primary function of dispensing cash, within a couple of years both cash machines and bankomats were online and performing a wide variety of functions (balance inquiries, taking deposits etc.) in addition to dispensing cash. By the time the U.S. got its first, true, ATM in Rockville Centre on New York's Long Island in the fall of 1969 (though claims are made for bankomat installed in California a few months earlier), the machine really did live up to its billing as an "automated teller".

In this regard, then, "cash machines" (in the places where they are known by this and similar names) suffer from the same branding problem as "mobile phones", in that the underlying technology quickly overtook the familiar name, causing a mismatch between function and nomenclature. So while "ATMs" have a head start in public perception, even they are still primarily associated with a cash-dispensing function that is increasingly redundant, at least in more advanced economies.

Artificially Intelligent Telling Machines

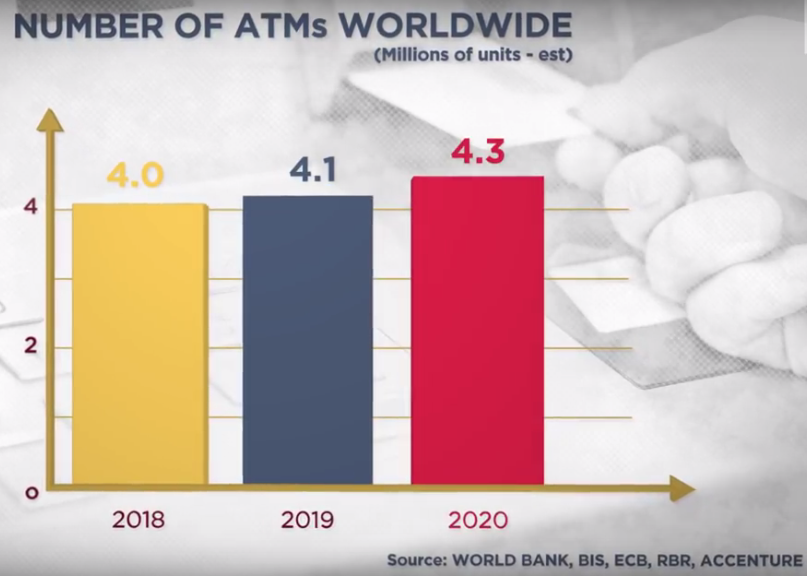

Globally, however, ATMs have never been so popular, with nearly 4 million of them in existence around the world, and another 300,000 expected to be in place by the end of the decade. And in many of the growth spots of Asia, Africa and Latin America, cash dispensing remains an important driver of growth.

Graphic courtesy of the FT

However, in many of these markets the previously un- or under-banked and/or growing middle classes are young, tech savvy mobile and/or digital natives, who often have little or no history with "traditional" banks or banking. This means they are both willing and able to carry out a wider range of transactions via a computer banking terminal (which also dispense cash, as an aside). Many of these new 21st-century bank customers have leapfrogged over CR-80 mag-stripe cards, straight into an exclusively digital relationship with the ATM.

So, while cardless ATM withdrawals are still a novelty in many parts of Europe and North America, they are old hat for large numbers of Latin Americans, for example, who get a one-time PIN texted to their mobile phone. NFC functionality on cheap smartphones looks set to displace even this technology within a short period of time, meaning customers will soon carry out most of their interaction with the machine via a mobile app interface, leaving just the "tap out" on the ATM's NFC antenna to complete the transaction and dispense the cash.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, refugees from Syria and elsewhere, many of whom have lost all docmentation, use biometrics far in advance of anything available elsewhere in order to access direct cash payments from ATMs. They can also use it to make payments directly from their World Food Programme account. Scanning users' irises as a means of both authentication increases security for both donors and recipients, and reduces long-term costs and leakage. It also allows for other administrative functions, such as information gathering and needs assessments, to be carried out by the machine questionnaires during the same transaction.

Filling A Gap

And despite all the gadgetry and gimmickry associated with ATMs in Dubai that dispense gold bars, bitcoin in San Francisco, or even a Silicon Valley company that wants to use drones to bring cash to you wherever you are, the waves of bank closures that have hit many advanced economies mean that standalone ATMs remain vital to the provision of a range of banking services, including access to cash, particularly in rural areas. So much so, for example, that within the past few weeks a debate was held in the British parliament on the future of free-to-access ATMs. In the wake of the LINK network's decision to reduce its interchange fees by 20%, concerns surfaced that this would lead to a wave of free-to-use bank ATM closures on cost grounds, increasingly leaving only "pay-to-play" ATMs on private premises catering to the £192bn of ATM cash withdrawals in the UK each year. Meanwhile, government and regulators are committed to the maintenance of a widespread free-to-use ATM network.

Nevertheless, it is inescapable that in many advanced economies the amount of cash in circulation is declining, reducing the need for cash dispensing ATMs, which need to be stocked, secured, cleaned and maintained, all at a cost. Basic economics say that these units will become increasingly nonviable as usage declines, even if they do offer a wide range of services (paying bills, taxes, obtaining government permits) in addition to simply dispensing money. And while the future of the ATM clearly lies in a combination of A.I. and remote access to staff via telelink that puts the 'T' back into ATM, these are the sorts of functions that are still much more likely to be carried out on in-branch ATMs, rather than on windy or sunny street corners, which will do little to ease concerns about the ax falling on less well-to-do ones.

While remaining important to socioeconomically marginalized communities, access to cash will continue to be market-driven, and ATMs will be important access points for this, and many other banking and civic services. But either way, much like the mobile phone, it seems quite likely that people will continue to refer to A.I.-powered robotic banking terminals (or whatever banking's digital future is) as "ATMs" or even "cash machines", long after they have ceased to dispense bits of paper money. Even as their functions grow closer in a way that the inventors of neither could scarcely have imagined, mobile phones and ATMs seem set to outlive us all.

Image courtesy of Garry Knight

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Bike Sharing & The Ecosystem Effect: China Versus The US

Mondato Summit Africa 2018: Demystifying Data