Mobile Money and the Ebola Crisis

~5 min read

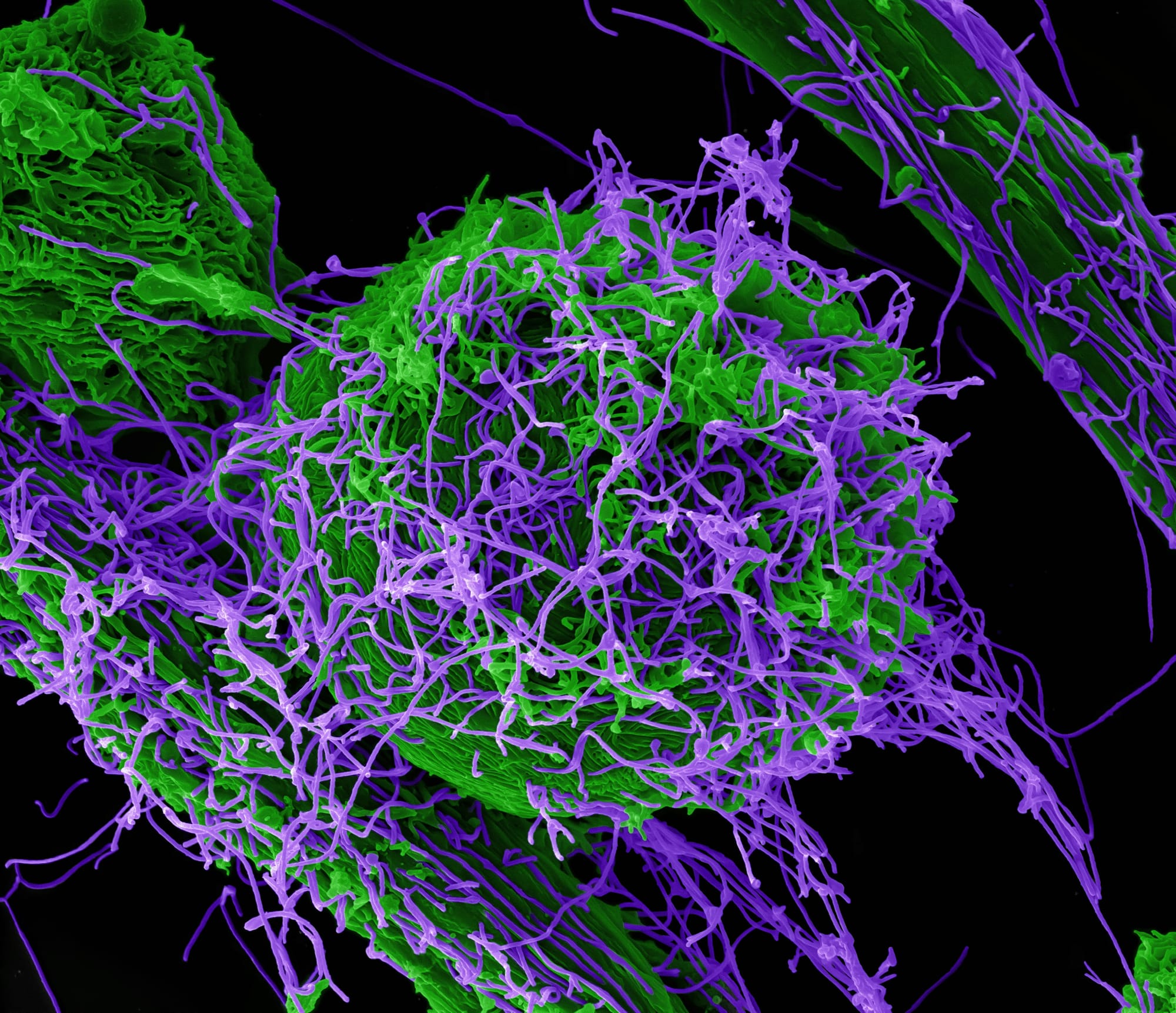

Although the Ebola virus that spread late last year through parts of West Africa claimed the lives of almost 9,000 people, the death toll remained but a fraction of some worst-case scenario predictions. 42 days will have to pass without a single new case before the World Health Organization will declare the epidemic over (and that day is probably still several months away). Nonetheless, public health management has turned towards ending rather than merely containing the outbreak, and many minds are turning to the aftermath of the crisis.

In the midst of the financial crisis that shook the world in 2008 and helped propel the Democratic presidential nominee into the White House, the U.S. president-elect’s confidant (later his chief of staff and now mayor of Chicago) Rahm Emanuel commented, “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is an opportunity to do things that you think you could not do before.” In this vein, the Ebola crisis has also shone some light on the potential, and limitations, of mobile phones in countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, both in times of crisis and normality.

None of the three countries at the center of the Ebola crisis of 2014 was at the forefront of the “mobile revolution” that some believe characterizes what is taking place in “Silicon Savannah”. While many African countries report mobile penetration surpassing or reaching saturation point, barely three out of five Guineans or Liberians have a mobile. In Sierra Leone, that number drops below half, and all three countries lie in the lowest decile of the 187 countries ranked on the United Nations’ Human Development Index.

Nonetheless, the opportunities presented by the “leapfrog” potential of mobile technologies were, and remain, huge: the larger the initial handicap, the greater the gap that can be leapfrogged. But in the early days of the crisis, many of the small but significant economic gains that had been made in recent years were jeopardized. In Liberia, for example, where 85% of daily market traders are women, the crisis saw inter-regional and cross-border trade grind to a near standstill in some areas, and forced traders to depend on savings for subsistence.

For many entrepreneurs, who had taken out loans from village savings and loans associations, or microfinance institutions, delinquent loans that were a direct consequence of the crisis posed a threat to both them, and potentially microfinance institutions. Part of the United Nations’ response saw the UN Women program deliver grants in the form of direct cash transfers to indebted entrepreneurs, via Lone Star Cell MTN’s mobile money deployment.

As Mr. Emanuel pointed out in 2008, however, it sometimes takes a crisis to cause a major rethink of what is possible or indeed necessary. As the head of the USAID-funded Liberia Investing for Business Expansion (IBEX) program observed last fall, “The Ebola crisis has really forced local businesses to change their economic activities and adopt new marketing strategies.” Part of that strategic thought shift was a re-examination of the role of mobile money platforms as a delivery channel for IBEX monies.

For many of those on the front line, however, (and indeed, those paying them) the value and importance of mobile money did not need to be explored or tested. In Sierra Leone, more than 16,000 Ebola response workers received ‘danger money’ payments via mobile money. Summing up the benefits of mobile payments, United Nations Development Program Country Director for Sierra Leone, Sudipto Mukerjee, said in interview, “Paying Ebola workers is paramount… We need to ensure that the right people are getting paid the right amount at the right time.”

There is, of course, nothing revolutionary about the use of mobile money in emergency disaster or public health situations. Mercy Corps, for example, in 2013 used mobile wallets to transfer money to 26,000 Filipino families in the aftermath of Super Typhoon Haiyan. Moreover, the NGO was already partnering with Lonestar Cell to use mobile money for grants and conditional cash transfers. Significantly, Mercy Corps’ Senior Advisor for Economic and Market Development told *Mondato Insight, *Mercy Corps had observed an increase in savings as a result.

While mobiles clearly have significant advantages and hold huge potential for the delivery and receipt of up-to-date information in very fluid environments, they may also require a degree of familiarity and training that truly emergency situations do not allow for. If all players are not fully familiar with the technology before a crisis breaks, and dependable electricity and GSM reception are unavailable, technology can actually act as an impediment rather than an aid.

When asked about this particular issue, the Center for Disease Control’s Joel Montgomery highlighted concerns that technology could get in the way of basic epidemiology. “We recognize that’s where we need to be moving, but we don’t want it to be a distraction either and the fear, from a public health perspective, is that these flashy softwares and the bells and whistles have the potential to distract.” Later in an interview with Al Jazeera, Dr. Montgomery was asked if other technologies had proved more useful than mobile technology. Laughing, he replied “Yeah, pen and paper.”

Unlike the markets in East Africa, many West African countries have been slow to seize the opportunity presented by mobile money. Ghana is the regional star pupil, but up to now the ecosystem was confounded by a quixotic regulatory environment. Nigeria, as Mondato’s recent report shows, has a huge addressable market and a large number of mobile money deployments, but low levels of adoption and usage. Sierra Leone and Liberia have, however, learned from observing the experience of these countries, and just last May Liberia promulgated a new set of mobile money regulations designed to loosed banks’ grip on mobile financial services and encourage a market-led growth in the ecosystem, just in time to allow mobile money to play a greater role in the response to the Ebola outbreak.

The practical lessons of this public health emergency for mobile finserv appear then to be less dramatic than Rahm Emanuel’s philosophical observation might have initially indicated. It may still, nonetheless, prove to be a catalyst to further spur developments that were already under way. As such, the Ebola crisis of 2014 may not have caused a reimagining of what is possible in West Africa, but it may help create a new appreciation for it: if all Ebola workers need in order to get paid the right amount on time is access to a mobile, then why can’t everybody?

<span style=color:#660033";>©Mondato 2015 Mondato is a boutique management consultancy specializing in strategic, commercial and operational support for the Mobile Finance and Commerce (MFC) industry. With an unparalleled team of dedicated MFC professionals and a global network of industry contacts, Mondato has the depth of experience to provide high-impact, hands-on support for clients across the MFC ecosystem, including service providers, banks, telcos, technology firms, merchants and investors. Our weekly newsletters are the go-to source of news and analysis in the MFC industry.

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Mobile Mary?

La Construcción de un Ecosistema Digital en Colombia