Eco Currency: Cash In Common For West Africa?

~8 min read

Against a post-Brexit backdrop, what can we learn from the internecine integration (and disintegration) challenges of other regions? Welcome to West Africa’s own will-they-or-won’t-they drama,unfolding with a familiar cast of characters and issues attached, but also featuring a new, postcolonial twist. In December 2019, the Ivorian president dropped a bombshell announcement intended to sever vestiges of French colonial control on former colonies’ financial systems while simultaneously increasing pressure on former British colonies to sign on to regional integration model with parallels to the Eurozone’s. National currencies and post-colonial sovereignty being the touchy subjects that they are, the conversation has naturally sparked a media firestorm. And the consequences of these currency contortions -- if Britain and the EU’s messy divorce was any indication -- are unlikely to be resolved quickly or cleanly.

Adieu la Françafrique?

For more than 50 years of independence, most former French colonies in West Africa have used a currency backed by the French government called the CFA - originally an acronym for “French Colonies in Africa.” Though the acronym has survived, what it spells out was eventually changed to something less, well, colonial.

But even after the name change (to Communauté Financière Africaine), France retained several aspects of control over the brand-new independent states’ financial systems. Perhaps chief among them was the requirement that 50% of treasury reserves of its former colonies be held in French banks. A French-held seat (with veto power) was also set aside on the board of African central banks’ governing bodies, ensuring a substantial degree of French influence over post-colonial monetary policy.

This arrangement safeguarded many of France’s colonial interests. That said, the bargain made by early independence-era African leaders paid off in at least some ways: while countries who opted to mint their own currencies have struggled to manage their monetary struggles, the CFA -- anchored in the stability of the European financial system -- has remained stable, yielding lower inflation, lower average unemployment, and a more predictable investment environment.

However, the current arrangement is due to end. In a joint announcement by Ivorian president Ouattara and French president Emmanuel Macron in December 2019, the treasury reserve and board requirements of the CFA will be phased out. Details of the CFA-countries’ new monetary structure are still being determined, but the majority of foreign reserves will continue to be held in Euros for now, and France will act as a guarantor of convertibility, ensuring a stable exchange rate with the Euro.

Enter The Eco

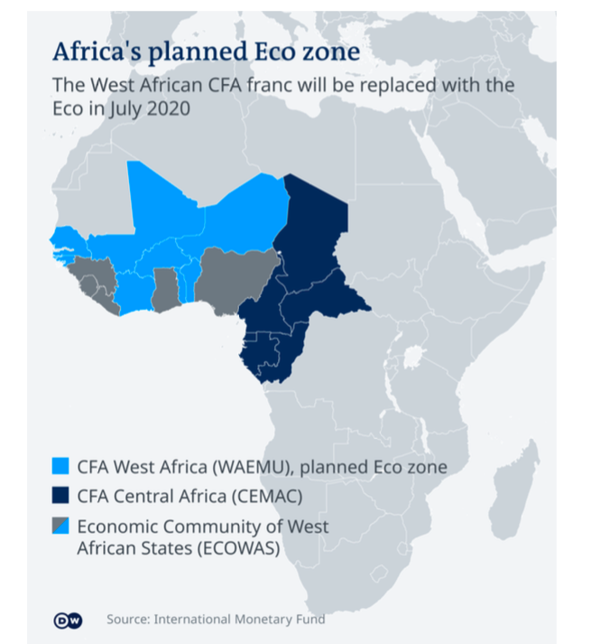

As these developments unfolded, Francophone Africans’ wish for greater monetary autonomy threw yet another wrench into the region’s monetary situation. Francophone and Anglophone West African nations, long keen on integration, have clashed over the name change intended to accompany the CFA’s touted de-Frenchification to the “Eco.”

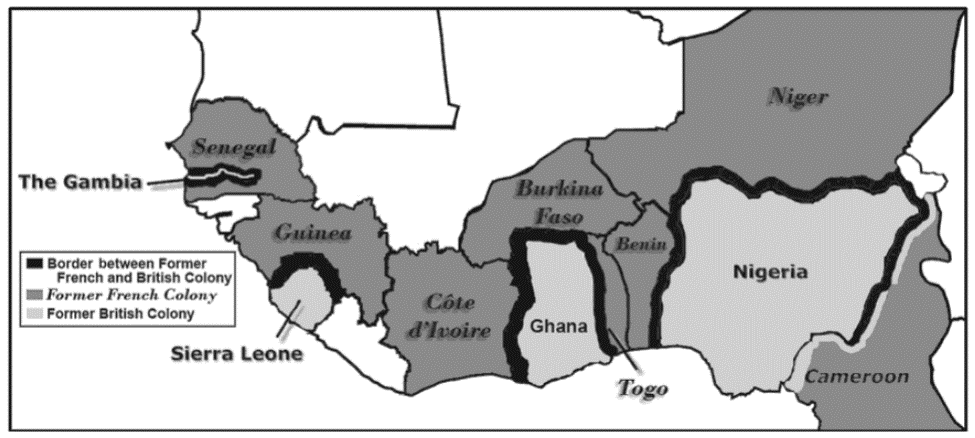

The controversy stemmed from the name itself. The name, “Eco,” was already taken by an existing movement promoting a common West African currency. For over two decades, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) - composed of 15 countries mostly demarcated by French and British colonial boundaries - had been working on a regional integrated currency, and had already agreed to call it the Eco (though, admittedly, not much aside from the name had been settled).

Source: Scars of Partition

By announcing the renaming of the CFA to the Eco, the CFA-block countries essentially bypassed endless discussions with Anglophone counterparts (led by Nigeria and Ghana) on what a common currency arrangement might actually look like, in what can be understood as a preemptive shot over the bow for West Africa’s vision of monetary integration. The official Nigerian response? “Not so fast.” Despite its exposure to global volatility and runaway inflation, Nigeria’s economy represents around 70% of the entire region’s GDP. Aligning with the CFA-inspired Eco would not only hitch smaller, struggling economies to Nigeria’s engine, but would also strip the country of some of its monetary tools and controls, such as the ability to print more money (devaluing her currency) during times of need.

[The WAEMU decision to rename the CFA franc as the eco]: “inconsistent with the decision of the Authority of the Heads of State and Government of ECOWAS for the adoption of the eco as the name of an independent ECOWAS single currency.”

Zainab Ahmed, Nigerian Finance Minister

The Shake-Out

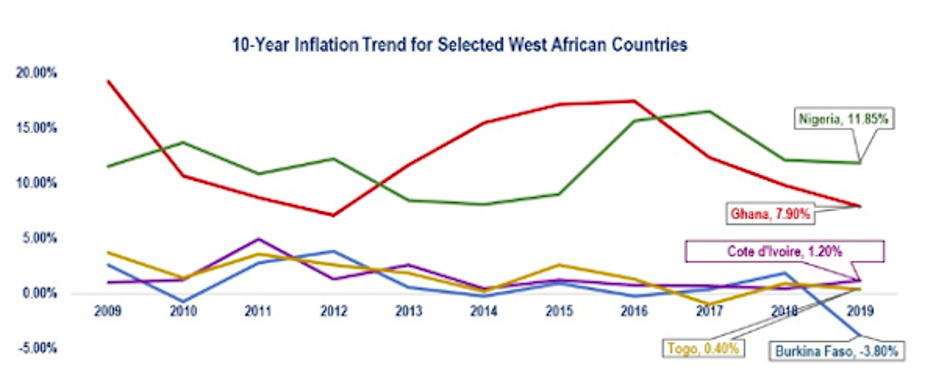

The proposed structure for West African countries adopting the Eco makes it clear that we likely won’t see new bank notes in circulation any time soon. This is principally because ECOWAS has agreed to a set of “convergence criteria” which countries wishing to get on board must meet - criteria that no country currently fully satisfies. These include: a budget deficit below 3% of GDP; public debt of no more than 70% of GDP; inflation of 5% or less; a stable exchange rate; and gross foreign-currency reserves large enough to provide at least three months of import cover. Togo appears to be the closest at present, while four other countries – Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, and Senegal – meet the requirements on inflation and budget deficits.

While this reality should set expectations for how seriously to take the target July 2020 adoption date, the political factors influencing the drive may reveal much about the state of affairs in West Africa. Importantly, the Eco’s unorthodox debut is a nod to the adage that all politics is local. Speculation as to the motivations for the timing of Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara’s announcement point to his upcoming reelection campaign, and the popularity points he scores by appearing to strong-arm the French into retreating from a deeply unpopular position of control.

Also relevant is Ghana’s role. Despite the cultural alignment between Ghanaian and Nigerian positions in ECOWAS as the two anglophone powerhouses, Ghanaian leadership has announced itself eager to join the Eco movement, despite the Francophones’ preemptive strike. We can at least partly attribute this divergence to a historical attachment to the vision of regional integration promulgated by first Ghanaian president and political revolutionary Kwame Nkrumah - or perhaps it is the Ghanaian cedi’s frustrating volatility that is pushing the country’s leadership to compromise with the Francophones flanking them on all sides.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators & Trading Economics

In a sense, West Africa’s regional integration questions mirror some of those taking place in Europe. If we indulge in the parallel: Côte d’Ivoire reflects the French integrationist sentiment, while Nigeria’s reticence recalls the United Kingdom’s cold feet around pitching in its lot with Brussels’. But that’s as far as the analogy holds. The superimposition of colonial boundaries across African geographies created an entirely new set of cultural, linguistic, and political borders for the present integration movement to contend with. To give a sense of the (mostly) arbitrary fashion by which these demarcations were drawn, it is perhaps useful to note that boundaries separating former British and French colonies continue to divide approximately fifty ethnic groups in Africa, including the Yoruba (Benin/Nigeria), Ewe (Ghana/Togo) and Hausa (Niger/Nigeria).

Any APIs for Culture?

From a business perspective, regional integration makes a lot of sense, particularly for multi-country operations and all things trade. But some firms -- particularly those already enjoying the stability of the CFA-zone -- worry about the medium-term transition period, particularly when it comes to foreign exchange controls. And from a man-on-the-street perspective, it’s clear that most citizens are very confused (French) as to what is driving the CFA-to-Eco switch beyond the long-awaited cessation of direct French monetary control.

What is increasingly clear, however, is that technology may outpace policy in promoting regional integration. In East Africa, the historical leader in mobile money payments, Safaricom and Vodacom have begun to reframe postcolonial boundaries by allowing mobile money users from Kenya and Tanzania to transact across networks and national borders more easily.

Scrappier West African startups like Bit Sika are taking a different tack to the same outcome, riding the cresting wave of African Fintech venture capital. They and others are making strides by picking the low-hanging fruit when it comes to regional integration by facilitating business through mobile payments between Ghana and Nigeria. Bit Sika’s success illustrates how blockchain, digital ledger, or other trust-protocol oriented payment technologies can bring needed transparency to the challenges of cross-border integration.

Emmanuel Asamoah, a Ghanaian tech analyst and enthusiast, notes that better-known and better-capitalized Nigerian companies like FlutterWave and PayStack have struggled to deliver such integration in reverse, perhaps reflecting the structural challenges that limit Nigeria’s Eco enthusiasm at the Central Bank level.

Given the growing interest in digital currencies by central banks around the world, perhaps West Africa’s governing monetary bodies will give Central Bank Distributed Curencies (CBCDs) a serious look - particularly in light of the buzz surrounding China’s e-yuan currency, the world’s first digital sovereign currency, which has been rolling out in limited and secretive fashion. But despite the cautious roll-out of this project (which includes cooperation with several commercial Chinese banks, Ant Financial and Tencent), it is likely to be a better bellwether of government appetite for crypto-based solutions to monetary policy than initiatives like Facebook’s Libra, which appears to be experiencing an exodus of partners.

Eco-lonial lines in the sand

Organizations who do cross-border business of any kind would likely benefit from being able to use a single common currency across the region. There’s overwhelming consensus that a regional currency like the Eco would boost intra-regional trade, increase efficiency, and reduce transaction costs. But the price of such an ambition is a serious - and creative - reimagining of the relationships between the region’s various players.

Whether ECOWAS leaders will seize the opportunity to leapfrog their colonial trappings into a cryto-led era of digital currency remains to be seen. Even in its ‘analog’ form, Eco’s success will depend on the negotiations which will unfold around its peg to the Euro (e.g., the flexibility of its convertibility, who gets to make adjustments, and how they get made). In this sense, the Eco will have to do what the Euro couldn’t: to effectively absorb and supersede the CFA, Naira, Cedi, and all the other West African currencies, it’ll have to make an even stronger case to Nigeria than the Euro did to the UK. We shouldn’t hold our breath.

Until then, it appears it will be Africa’s entrepreneurs and innovators who will lead the charge in regional integration, by connecting opportunities around, through, and sometimes thanks to the cultural and linguistic borders that were drawn mid-century.

In separating the posturing of political discourse from the pragmatics of business as usual on the ground, it is perhaps appropriate to focus on the specific geographies and populations who are already “regionally integrated” - border peoples. For dwellers straddling national boundaries, postcolonial borders have for decades been viewed more than simply an indignity to efface - but rather a line to be traversed or leveraged where possible.

Preeminent African border scholar Anthony Asiwaju writes that African governments would do well to recast their borders as bridges rather than barriers, giving priority in the decolonization of the map of Africa by changing the character of colonial boundaries rather than their physical appearance. Perhaps the same could be said for their currencies - much more important than the name of the currency is what it can accomplish for the people. Let the politicians remember that the divisions they inherited are enduring but malleable - or as Asiwaju points out, that a border can divide, but can also unite.

Image courtesy of Eva Blue

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Do Women Hold The Key To Financial Inclusion In Mozambique?

Open Banking: API Use Cases To The Rescue