Are The Economics Of Cash Crumbling?

~7 min read

Since the dawn of civilization, physical currency has been the backbone of everyday commerce. But in 2019, prophesies abound of a potential collapse in the world’s cash-based system. The reality, however, isn’t so simple. All the trends point in one direction: the use of cash is crumbling, which is undermining its economics. Among countries who have nearly vanquished cash, a scramble has commenced to in fact save it from a premature demise. Why?

A Rapid Deterioration

Across the globe, governments of emerging markets are pushing through legislation and regulation to facilitate cashless payment solutions, ranging from Singapore to Nigeria. Reasons to digitize payments are manifold: the high cost of handling and processing cash, increasing tax receipts, curbing corruption and organized crime, and bringing oversight to the broad informal economy.

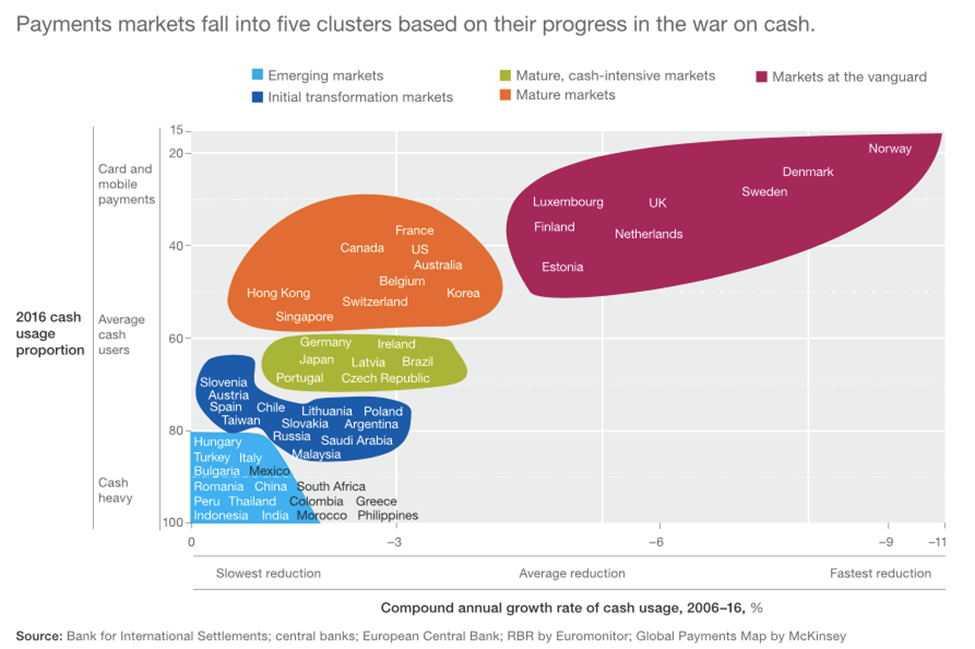

As the below infograph from McKinsey displays, the “vanguard markets” of Northern Europe are abandoning cash far quicker than other countries. Some usual suspects, however, are bucking expectations. Many mature markets like Japan and Germany are slower to ditch cash due to cultural preferences; as Mondato Insight previously described, it isn’t merely market forces, but a digital payments-friendly culture that enables Nordic countries to adopt digital payment methods so readily.

And, it is not just the Northern stars — countries still heavily dependent on cash are drifting towards digital payments as well. Is it that digital payments have a clear economic edge on cash? Not always. Even in more advanced, highly digitized economies, factors like processing fees may render cash more favorable for individual contractors and small businesses. The UK’s Access to Cash Review reported passionate (and conflicting) testimonials from businesses, with some claiming cash as the cheaper alternative, while others steadfastly defended digital transactions as the thriftier choice.

In 2016, the British Retail Consortium published that direct cash costs were “markedly cheaper” than card payments. In the UK, the .5-.9 percent cost for merchants processing cash is currently about the same as digital payments. But the economic tea leaves prove grim for paper money. BRC’s proclamation in 2016 came without accounting for the myriad of “hidden costs” of processing cash, which can make running a business with cash untenable.

Consider a recent report by IHL Group, which found that cash handling costs for retailers in the U.S. ranged from 5 to 15 percent for a 9.1 percent average across all retailers. In 2017, the costs of cash handling activities by retailers in the U.S. and Canada were estimated at an astounding USD$96 billion – the GDP of Ukraine. Among warehouse clubs and super center retailers, IHL Group found cash handling to cost on average 1,122.4 hours of labor per month per store.

“Most often, retailers task the most expensive employees in the store to count and transport cash, which means these employees are not available for other, more profitable customer-facing transactions." Greg Buzek, president of IHL Group

As consumers switch to digital payments and businesses start shunning cash, the vast physical cash infrastructure built for a time of high cash demand and supply is beginning to fail — and digital-friendly regulation is further tipping the scales. Since the BRC declared cash costs to be cheaper, UK regulators capped digital payment costs in the UK to .2 percent for debit and .3 percent for credit, while concurrently mandating that transaction fees are relative to value instead of fixed, which encourages digital payment methods for smaller, everyday purchases.

The fixed nature of cash’s infrastructure costs renders it increasingly unstable as people rely less on cash. In the UK, ATM cash usage is falling about 6 percent each year, with the UK and its £5 billion cash infrastructure losing 4,500 ATMs in 2018 alone. Access to Cash’s UK study found that the biggest drivers of merchants and retailers refusing to accept cash were the rising costs of handling, and banking, cash.

“As bank branches and ATMs close, cash is becoming less available, meaning its usage is dropping at an alarming rate, justifying further closures.”Federation of Small Businesses

We Might Need A Doctor

As Mondato Insight has previously discussed, the “creative destruction” of technological advancement in capitalist societies risks leaving people behind. But, the concerns go beyond ethics. Transitioning to a totally cashless ecosystem may empower private digital transaction operators to hike fees at will. The entire financial system would be vulnerable to cataclysmic hacks. In times of financial crisis, people may have no alternate safe haven from banks and private firms. With some citizens of even the most advanced markets at risk of financial exclusion, the economic effects of abandoning cash completely can be disastrous without proper preparations.

As commissioned by LINK, the UK’s Access to Cash report called for action not before cash goes extinct, but before it simply can’t be used. According to its exhaustive report, cash went from comprising six out of every ten transactions to only three in ten in a decade. Although straight-line projections forecast an end to cash in the UK by 2026, Access to Cash’s review determines that some 10 percent of payments in the UK will be in cash in 15 years due to a small population remaining dependent on cash.

Shortly after the review was published, however, industry sources warned the cash payments system in the UK may collapse in two to five years, as companies involved in the circulation and distribution of coins say trends “towards digital payments will soon render their businesses unprofitable.” Access to Cash found that 17 percent, or over 8 million adults, of Brits would struggle to cope in a cashless society.

In Search Of A Cure

To keep cash afloat in such digitally advanced markets, several possible solutions are being tossed around. Countries like China, Denmark and Norway have passed legislation to require cash acceptance by merchants — though enforcement has been spotty. Philadelphia recently became the first major U.S. city to follow suit.

One proposed model, which the Access to Cash review suggests, is to shift the conceptualization of cash from a public asset to a public utility. This could potentially involve restructuring wholesale cash supply chains into utility models, having banks pool resources to form a shared cash-handling network that increases the efficiency of the ATM network while maintaining access for consumers. Such models have made their way to cash-averse Scandinavia, where Sweden and Finland have replaced bank-branded ATMs with a nationwide utility provider jointly owned by banks.

A more watered-down version in countries like Denmark, Norway and Italy utilized shared cash-counting centers in regional hubs. McKinsey estimated that consolidating resources can save banks up to 35 percent in ATM costs. By reducing the commercial stake for an individual bank in deciding where to operate ATMs, vulnerable consumers can be better protected.

On a more abstract level, UK’s Access to Cash expressed the belief that “cash access and acceptance will need to be seen as a utility: an essential function of maintaining an inclusive society, even if it doesn’t make much commercial profit.” By creating regulations to guarantee cash access as akin to water or electricity, the stable and secure components of cash can be preserved for the time being.

In Sweden, where only 13 percent of Swedes reported using cash for a recent purchase - and the majority of local banks have stopped letting people take out or deposit cash - an even more radical option is being considered for a cash-scarce future. Sweden’s Central Bank, the Riksbank, is exploring the idea of a digital currency, the “e-krona.” The “e-krona” would be a digital counterpart to cash issued by the Riksbank.

An e-krona would both be a government-guaranteed means of payment without credit risk and be available in digital form as a complement to cash. And as an addition to already-existing payment forms, the Riksbank believes the e-krona would increase competitiveness and serve as an alternative, non-commercial means of payment in the market and during fiscal crises.

The e-krona has the potential to counteract some of the threats posed by a largely cashless society. Like RIX, Sweden’s digitized system for large value payments, the rails of the e-krona would constitute an entire payment system with a technical infrastructure that provides the general public access to the e-krona. Functioning independently from commercial banks’ infrastructure, the e-krona could make the payment system more resilient against threats to card payments. The Riksbank has yet to determine how exactly it will leverage existing digital infrastructure and external actors in terms of end-user design. The e-krona’s separate non-commercial payment system, too, would theoretically compel private payment players to keep fees at bay.

The Riksbank’s study looked at two forms: a register-based e-krona, in which account balances are stored in a central database, and a value-based e-krona, which would be stored locally in an app or on a card. A register-based e-currency would work best for larger payments, the Riksbank concluded, while the value-based register could be implemented more quickly and be used for smaller payments.

A Forced Resuscitation

However, for all the solutions being proposed — treating cash as a public utility, implementing regulations and subsidies to keep cash economically viable, creating a government-backed digital currency — the fact remains that most markets do not have to make such decisions just yet. Curiously, as cash usage has declined, cash in circulation (CIC) has actually increased.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco went so far as to boldly conclude that “reports of the death of cash” are “greatly exaggerated.” Though the percentage of transactions made in cash have fallen across the board, the Californian Fed’s study pointed out that among 42 economies across the globe accounting for 75 percent of world GDP, the growth of CIC matched or exceeded the growth of GDP in all countries except Norway and Sweden. Reasons suggested include the low interest rates in many countries the past decade, inflation — though the growth of CIC has outstripped inflation — a growing informal economy, and mistrust of the financial system.

Yet even while the volume of cash in the British economy increased, the value of payments in cash declined more than 10 percent. There is little doubt that cash’s dominance is coming to an end. But until the problems of a fully digitized payment system — concentrated power among digital payment providers, vulnerabilities to hacks and financial crisis, a lack of financial inclusion — are solved, cash can’t go away categorically. Even where cash use has plummeted, warning signs encourage nervous governments to work towards ensuring the viability of cash’s infrastructure until systemic issues are addressed. How long that will take is an open question and likely depends on the place. Until that happens, cash in vanguard markets needs to be put on life support — stat.

Image courtesy of European Central Bank.

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Fintech Funding Strategies: Series B To Unicorn

Will Big Tech Dwarf Fintech?