How DPI Determines the Shape of Sovereign AI

~9 min read

As the sovereign AI race heats up, countries are now seeking to implement and integrate AI within their preexisting digital public infrastructure (DPI). At first blush, it may appear to be artificial intelligence that’s primed to transform digital public infrastructure — making identity systems predictive, payments rails self-monitoring and public services adaptive to citizen needs. But no country is building out its sovereign AI capabilities on an infrastructural blank slate. The infrastructure decisions governments made over the past decade — how identity systems were designed, who governs payments rails, whether data exchange is centralized or federated — are now determining where artificial intelligence can realistically be embedded, and who will control it once it arrives.

When AI Hits the Rails

Integrating AI with DPI does not overhaul the stack. It layers onto it — if sometimes awkwardly. Digital public infrastructure was designed to perform predictable tasks: authenticate identities, clear transactions, verify eligibility and execute rule-based administrative workflows. These systems are expected to be auditable, legally defensible and operationally deterministic. Artificial intelligence, by contrast, introduces a very different logic: probabilistic outputs, adaptive learning systems and model behavior that is often difficult to fully interpret.

That mismatch forces a harder question: how much probabilistic decision-making can critical infrastructure tolerate?

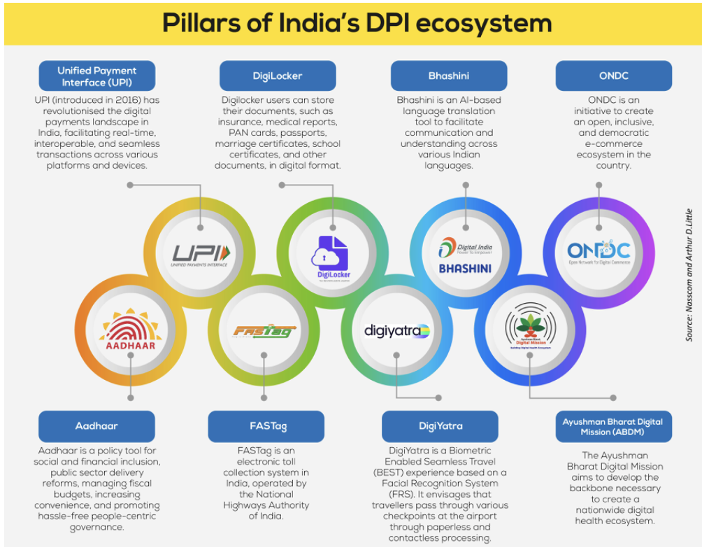

Anit Mukherjee is a senior fellow at ORF America who helped create the architecture for India’s Aadhaar and UPI systems, the leading example in the world of truly integrated, centralized digital public infrastructure. Looking back at when they were first piloting the Aadhaar system registering the biometric ID of 1.3 billion people in India in 2009, “being able to authenticate online was completely illogical,” Mukherjee recalled, considering it was mostly 2G networks back then. But the infrastructure was built with the idea that cell phone technology would improve over the years, enabling the infrastructure to incorporate expanding use cases and data silos over time. All of this gave rise eventually to India’s United Payments Interface, a centralized platform enabling billions of transactions per month.

With those additions over time, the nature of the India stack has evolved far beyond what Aadhaar originally premised. “The India stack — the ID, payments, data exchange — that itself has kind of evolved into identity management,” said Mukherjee.

Source: Iasgyan

Source: Iasgyan

That is because DPI, when constructed right, should be additive by nature. In Mukherjee’s eyes, what made the India Stack so successful in going far beyond biometric IDs to encompass so many other use cases was its infrastructural openness, bridging data siloes and creating a seamless inclusion for India’s 1.3 billion citizens. As these features are added, “you don’t close off the system,” said Mukherjee. “You grow with the new technology, but you try to also upgrade your safeguards, depending on what is the technology that is on offer; when quantum [computing] comes in, everything will be about cryptography.”

The Digital Impact Alliance (DIAL) has been working with partners in Nigeria to bridge this gap between AI innovators and policymakers. “The implementation of AI layered on top of DPI, they're not siloed conversations,” said Adeola Bojuwoye, the Nigeria Project Lead at DIAL. “They're so well-intertwined. AI depends on a really good foundational layer, DPI, to be valuable.”

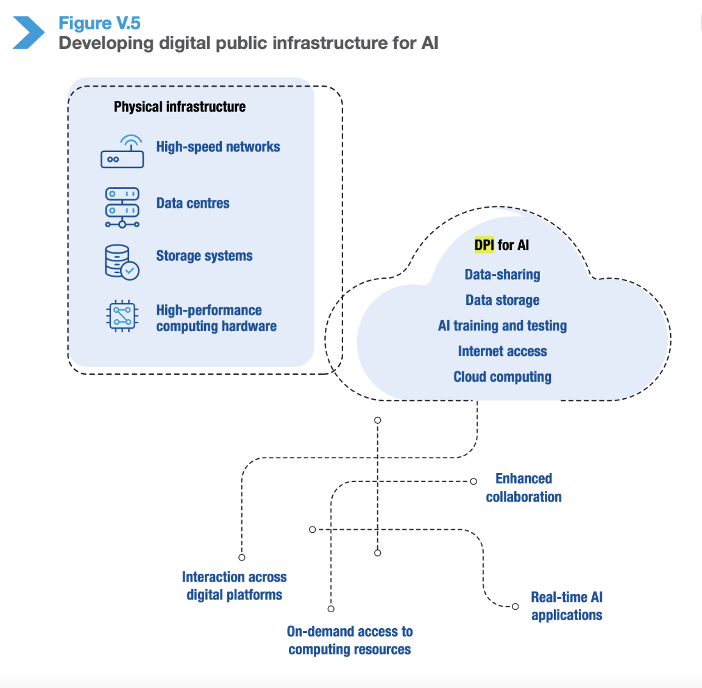

Source: UNCTAD

Source: UNCTAD

Implementing AI requires clean, consented data, particularly when originating from DPI frameworks with strong data protections. And when applying AI to possible use cases like fraud detection, “what kind of structures already exist, what kind of content mechanisms are already in place, that AI is then able to add value to deepen those conversations,” said Bojuwoye.

When it comes to data exchange — “the vertical that's really going to benefit a lot from considerations around AI infusing DPI,” as Bojuwoye put it — the question becomes how public agencies can transfer data “in a way that minimizes exposure of personalized data, minimizes unnecessary requests for data” and ensures that such data can be easily synergized across government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs).

“That's what we're starting to realize: it's not DPI for AI or AI for DPI. It's more or less that nexus between the two.”

Adeola Bojuwoye - Nigeria Team Lead, DIAL

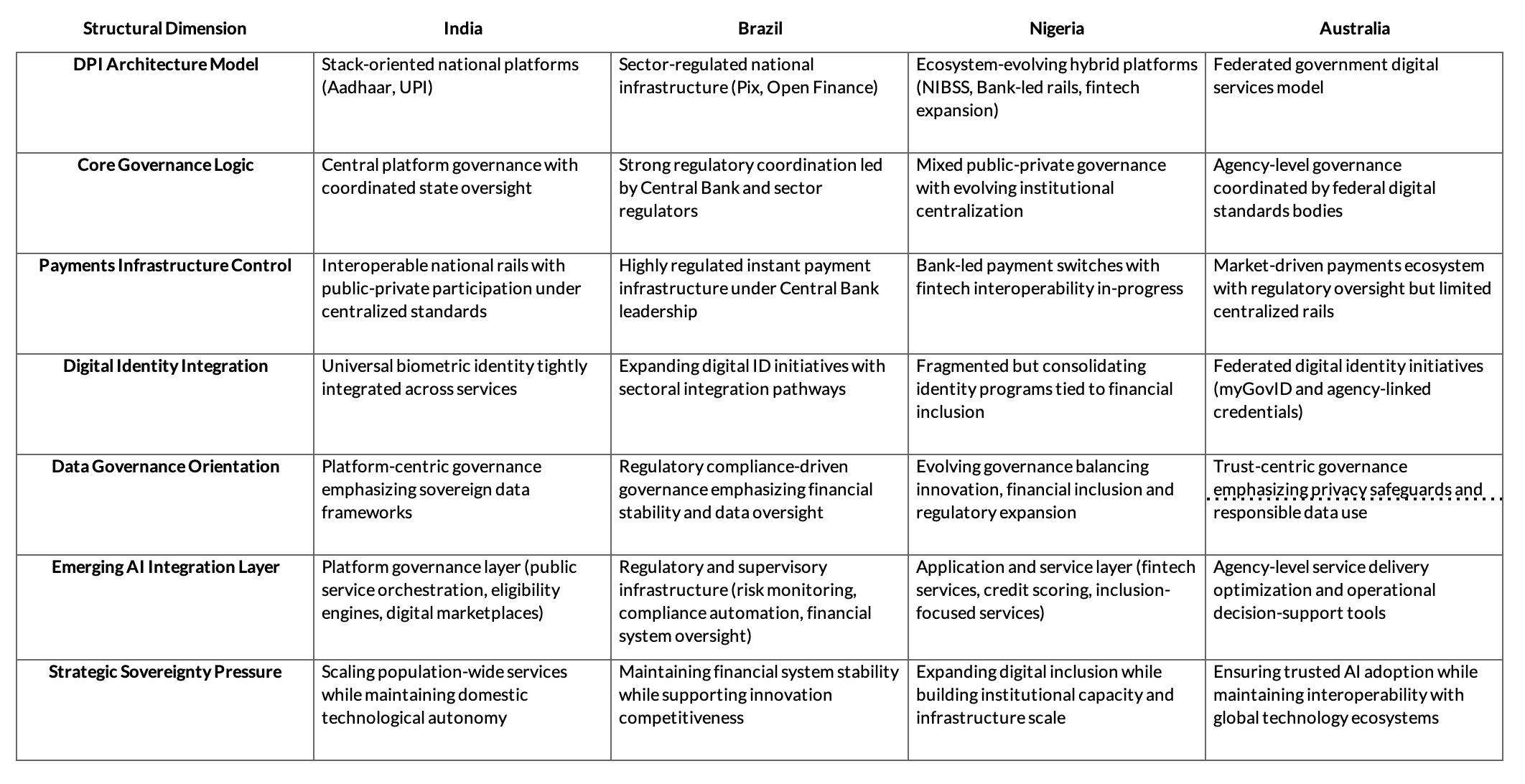

But the nature of the relationship changes according to the foundational DPI characteristics. Countries like India whose DPI was built as centralized interoperable stacks can insert AI directly into infrastructure governance layers because the institutions that manage identity and payments rails can also define model oversight rules. Where DPI is organized around powerful sector regulators, like in Brazil, AI tends to be integrated into supervisory infrastructure — such as fraud monitoring, systemic risk detection and regulatory compliance systems. In ecosystems where infrastructure is still evolving through public-private innovation, like in Nigeria, AI may appear first in applications rather than infrastructure, driven by fintech platforms and service providers rather than infrastructure operators. Federated government systems, like in Australia, are likely to adopt AI through coordinated agency-level deployments, with governance frameworks emerging gradually through cross-government standards that are still being developed.

The Architecture Decides

These institutional differences shape where AI can realistically be embedded — and who governs it once deployed. In India, interoperable national rails such as UPI generate vast volumes of standardized transaction data flowing through a common infrastructure layer. This architecture makes it possible to embed fraud detection, anomaly monitoring, and analytics capabilities directly into the payments stack itself — infrastructure-level intelligence rather than institution-level tooling. The same stack-oriented approach underpins identity-linked service delivery through Aadhaar and data exchange frameworks such as the Account Aggregator system, creating a governance environment where AI deployment can be orchestrated at the platform level.

An example of this is Hello UPI," which allows users to initiate payments using voice commands in multiple languages. This is powered by AI-driven speech recognition and intent verification layered directly onto the payment rail. India’s Bhashini system acts as an AI-driven translation layer, creating linguistic accessibility for public services by crowdsourcing language data (BhashaDaan) to train localized models.

Brazil’s experience highlights a different pathway. While its broader digital ecosystem is decentralized, the Central Bank’s tight regulatory control over the Pix payments system — shaped in part by decades of financial instability — has concentrated operational authority within the regulator itself. That institutional design, says Mukherjee, is now steering AI integration toward supervisory infrastructure, where machine learning tools enhance fraud detection, transaction monitoring and systemic oversight embedded in the regulatory apparatus.

India and Brazil, of course, stand out for their advanced digital public infrastructure compared to peers especially when considering the massive popularity of both UPI and Brazil’s PIX instant payment system. In the case of Nigeria, however, its digital infrastructure remains an evolving ecosystem rather than a unified national stack. In such environments, AI deployment naturally begins at the service layer — onboarding verification, credit scoring, fraud analytics — rather than at infrastructure governance levels. The Nigerian Data Exchange Platform (NGDX), a new digital infrastructure designed to unify data sharing between government agencies and businesses, is still in its last stages before full deployment. “The objective is the same” as the India Stack, said Bojuwoye, but its setup and governance reflect a more ecosystem-driven and private-sector-inclusive model compared to India’s more centralized, state-orchestrated approach.

The NGDX is structured to bridge the data bottleneck that often prevents services from reaching underserved Nigerians, serving as a centralized gateway for government databases to connect through standardized APIs. Unlike the India Stack, which centralizes everything on the government platform, the Nigerian model intentionally creates pathways for private-sector innovators. For example, the fintech XChangeBOX leverages data made available through such DPI rails to create credit scores for unbanked individuals based on alternative trade data. But importantly, the NGDX is structured to ensure that the data remains a “strategic national asset” that isn’t simply extracted by external tech firms.

This includes efforts to build regional data centers and local compute capacity to reduce reliance on global cloud providers — a challenge magnified by the less forgiving cost curves in building out AI infrastructure and localized data center infrastructure, which only grows in cost with scale, than compared to DPI, which becomes more cost-efficient as scale grows.

Comparative Structural Dimensions Shaping AI–DPI Convergence

Though still a work in progress, Australia’s federated government digital architecture produces a different integration logic altogether. Rather than embedding AI into a single national infrastructure layer, adoption is being coordinated across agencies under common governance standards. The Australian Public Service (APS) AI Plan 2025 focuses on creating shared AI tools and secure platforms, such as "GovAI Chat," while prioritizing trust and ethical use.

“Keeping trust with the Australian people is critical to successful adoption of this new technology… clear guidance, strong governance settings and the capabilities needed to support safe, effective and accountable use of AI across agencies.”

Ramsey Beydoun - AI Branch Manager, Australia’s Digital Transformation Agency

Who Controls the Data Controls the AI

Payments infrastructure is becoming one of the most consequential entry points for AI integration because transaction networks generate continuous high-frequency data streams essential for fraud detection, credit analytics and behavioral modeling. Where those data streams are centralized — as in India’s UPI ecosystem — infrastructure-level intelligence becomes feasible. Where they are regulator-controlled — as in Brazil — supervisory AI systems become the primary adoption pathway. Where payments ecosystems remain multi-stakeholder — as in Nigeria — innovation is driven primarily by service providers like XChangeBOX, which uses AI to create "trustworthy" services for underserved populations.

These infrastructure economics are pushing policymakers towards the conclusion that AI sovereignty debates cannot be separated from DPI investment strategies. In Brazil, for instance, the AI Plan 2024–2028 allocates significant funding toward a "sovereign cloud" and the expansion of supercomputers to manage national data independently of external tech giants.

At the same time, someone like Bojuwoye believes that in an African DPI-AI context, the concept of sovereignty needs to be “reimagined.” Bojuwoye offered the example of a Big Tech representative who was offering Nigeria “sovereignty-as-a-service” — “which is funny concept because it means you're arguing for sovereignty, but someone actually manages that service on your behalf, which isn't really sovereignty.”

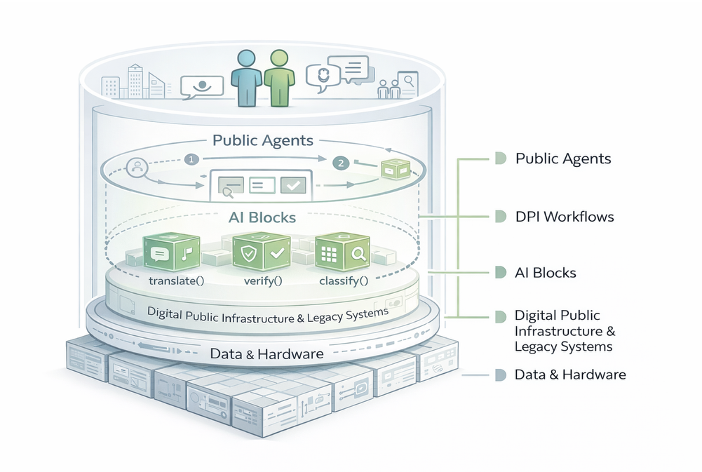

Transforming Digital Infrastructure into Living, Adaptive AI-Enabled Public Services

Source: digitalpublicinfrastructure.ai

Source: digitalpublicinfrastructure.ai

But the extraordinary cost curves of building AI infrastructure, in contrast to DPI, demands a different way of approaching the AI-DPI nexus as a private-public partnership — regardless of the exact DPI model, but especially where government budget and local economics demand private sector involvement.

“When we think about data, computes, models, the concept of how it works needs to be rethought when we think about countries and entities that are not in a position to actually negotiate for these services. Because if you're not able to scale up infrastructure in an efficient way that supports what is on offer elsewhere, it then becomes a choke point along the entire value chain for DPI.”

Adeola Bojuwoye - Nigeria Team Lead, DIAL

Bojuwoye sees one promising avenue to overcome these obstacles in the form of regional data centers, which in Africa may drive down costs and improve access to AI systems. Regional payment systems may further reshape these dynamics. Initiatives such as the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), as Mondato has discussed before, are designed to create interoperable cross-border settlement rails that could eventually support shared fraud-detection infrastructure and transaction analytics across multiple jurisdictions. If realized at scale, such systems could become not only shared financial infrastructure but shared AI infrastructure — particularly for countries that lack the compute capacity to independently build large-scale supervisory systems.

The Feedback Loop

The policy conversation often frames the relationship between artificial intelligence and digital public infrastructure as a directional choice: governments either deploy AI to improve DPI systems, or they invest in DPI to enable domestic AI ecosystems. In practice, the relationship is circular. Identity systems, payments networks and interoperable data exchange frameworks generate structured administrative datasets — precisely the inputs required for sovereign AI training and deployment. AI tools, in turn, improve fraud detection, infrastructure monitoring, service delivery optimization and regulatory oversight.

However, the "AI for DPI" model introduces significant risks of exclusion if not governed contextually. In some contexts, AI-driven decisions can cause errors, such as a social security app in Brazil that was found to be incorrectly rejecting claims. In the case of Bhashini in India, when people with low digital literacy interact with these systems, they sometimes accidentally reveal personally identifiable information, potentially corrupting datasets or compromising privacy, according to DIAL.

Taken as a whole, the divergence in AI adoption pathways is not fundamentally about differences in ambition or policy rhetoric. It is about institutional inheritance — the governance structures, interoperability philosophies and regulatory arrangements embedded in each country’s digital infrastructure. As AI is layered onto preexisting DPI, the key will be doing so in a localized manner that is pragmatic, technocratic and continuously evolving rather than being rigid and politically driven. Sovereign AI will not be decided solely by who trains the largest models or passes the boldest strategies. It will be decided by who built adaptable digital rails long before the AI boom began — and who can now govern the intelligence running on top of them.

Image courtesy of Google DeepMind

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Agentic AI and the Remaking of the Financial Services Stack