The Conundrum Of Chargeback Fraud

~8 min read

Chargebacks are a tool simultaneously essential to digital commerce, yet one deeply vulnerable to abuse. Chargebacks occur when a consumer disputes a card transaction directly with the bank, getting their money back at the cost of the merchant, who also incurs a chargeback fee. With general payment fraud on the relative decline as greater authentication measures are put in place, a quickly increasing slice of chargebacks are the result of “friendly fraud” – in which the card holder themselves initiate the chargeback for improper reasons, intentional or otherwise. As fraud measures focus on hackers and fraudsters, the near-impossible ways to discern whether first-party chargebacks are legitimate claims, the products of misunderstanding or a tactic to essentially keep products for free, highlights a fundamental philosophical gap in fraud security regimes that even big data can only go so far to detect.

Engendering Trust… And Fraud?

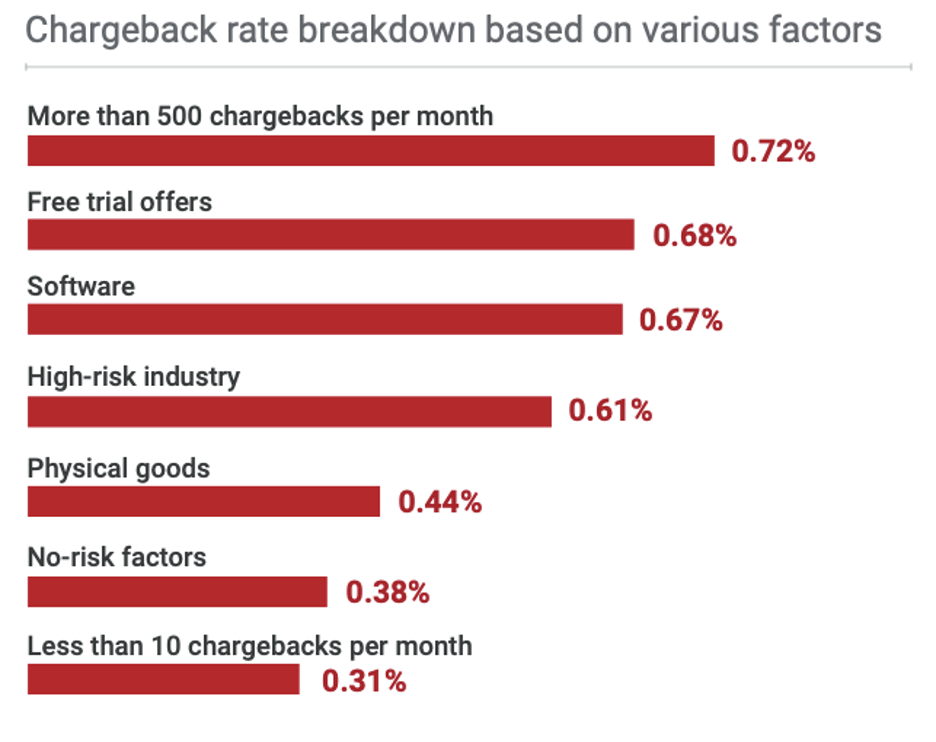

Chargebacks originated with credit cards themselves, serving as a mechanism to engender trust so that even in the case of card theft or fraud, consumers are guaranteed to get their money back. Such rules, created by card issuers and enforced by banks, have built in an inherent bias favoring the consumer over merchants in dispute resolution, with little required for consumers to swiftly get their money back. Yet this regime was created decades ago, long before the Internet and ecommerce transformed the financial payment process. If a business’ chargeback rate exceeds a certain ratio — Visa’s threshold is .65%, while Mastercard’s is 1%, for reference — then a business would be placed on a monitoring program, charged with monthly fines and fees until the ratio falls.

Yet while statistics vary, all indications point to a chargeback system increasingly rife with abuse. One survey suggests as much as 86% of chargebacks are the result of abuse. Yet both the stated reasons for chargebacks — as well as the true nature of such chargebacks — vary. About 30% of chargebacks are purportedly a result of transactions made with a stolen card — serving the intended purpose of chargebacks. 26% are the result of purchases never being delivered. Yet such claims — which banks invariably accept at face value — belie how often opportunistic or criminal elements exploit the convenience of chargebacks.

“We had someone in the US claiming they didn't receive a swimming pool. Google Maps shows the swimming pool in their garden — that is how blatant some people are.”

Ed Whitehead, Managing Director, Signifyd

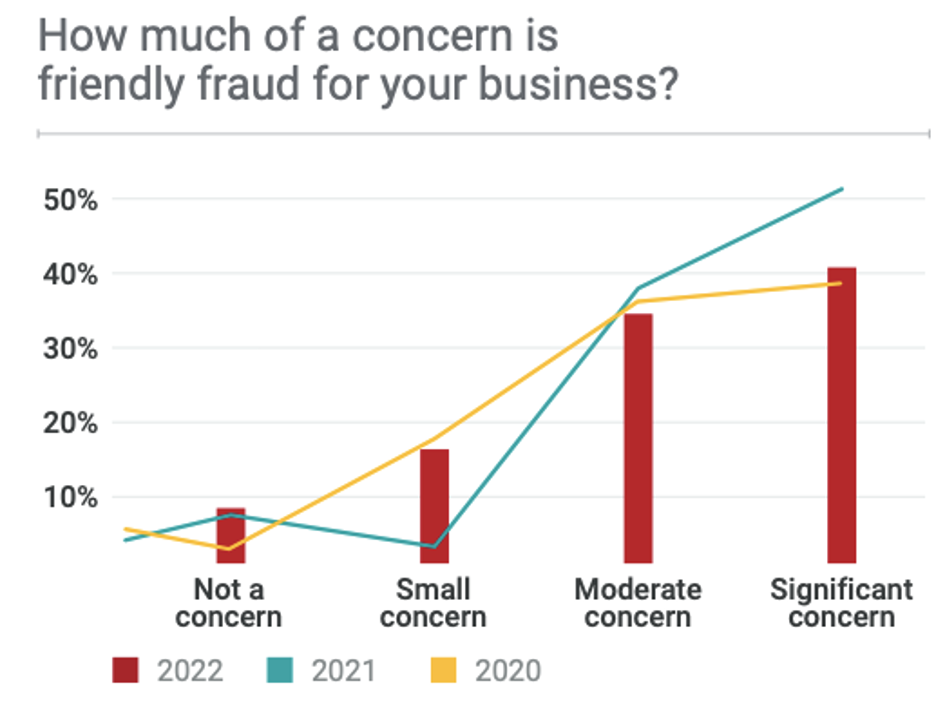

Especially since the pandemic began, as digital acceleration has made chargebacks even easier to do — 81% of customers admitted “convenience” was their primary motivator in filing a chargeback — chargeback rates have skyrocketed. In the most recent Chargebacks911 Chargeback Field Report, approximately two-thirds of merchants reported a rise in friendly fraud over the past three years, with an average increase of 28%. And the issue doesn’t only haunt high-end retailers.

“One thing that’s surprising is how low the bar is for someone to try and defraud, to cause a chargeback. You think it's going to be Rolex watches, high value items online, and it is, to a certain degree. But a $20 food delivery, a $10 cab ride, they're also susceptible, if not more to it.”

Gerry Carr, Chief Marketing Officer, Ravelin

A merchant can dispute a chargeback, but this process, called representment, is difficult and time-consuming. According to Chargebacks911, approximately 72% of merchants challenge chargebacks, but of the 42% of chargebacks that merchants believe are caused by friendly fraud, they contest just over half of that 42%. With a win rate of approximately 45%, this comes out to a chargeback reversal of approximately 10% of all cases — a figure that is even lower when factoring second-cycle disputes that customers can subsequently file.

As Harlan Hutson, director of strategic partnerships at Chargebacks911, explains, chargebacks broadly fall into three categories. There is true criminal fraud, in which a bad actor obtains someone’s card information to use for a transaction, and the true card owner initiates a chargeback with their bank. About 30% of chargebacks are of this nature, says Hutson. The second category is merchant error: the wrong item is sent, a delivery isn’t made, or the name of the billing company differs from what the customer expected, among other examples. Though only 8% of merchants identified such issues as a primary concern in Chargebacks911’s 2022 survey, this underestimates the scope of this problem; Hutson says Chargebacks911 has identified over 400 such ERTs — errors, risks and threats — among client businesses.

The third category of chargebacks sounds the most innocent, yet it’s the most difficult to rectify: friendly fraud. Friendly fraud occurs when the card owner initiates the chargeback process either because they aren’t aware they or a relative initiated the transaction or, more nefariously, are exploiting the convenience of chargebacks to get their money back while keeping the delivered product.

The very nature of friendly fraud presents profound challenges to merchants and fraud prevention companies. Mechanisms to detect digital payment fraud largely rely on indicators — like IP addresses or other forms of data suggesting third-party fraudsters — that appear completely normal in the case of friendly fraud. In the case of one-off, opportunistic friendly fraudsters, it can be near-impossible to catch.

Data, Seen Or Unseen

With card issuers driving such rules and banks enforcing them, chargebacks are a largely unregulated domain. The EU’s PSD2 regulation and 3DS requirements have managed to tamp down much of the third-party payment fraud that ran rampant, but it does little in addressing first-party fraud, which has increased.

“As you squeeze one point of frauds, then it moves to the others. And legislation in Europe has definitely squeezed the checkout fraud piece; it's very easy to detect stolen credit cards, you have to authenticate at checkout. But it's a little bit easier for these fraudsters to abuse returns policies, or to claim that they never received the item.”

Ed Whitehead, Managing Director, Signifyd

Nobody in the fraud prevention industry believes that regulation alone will ameliorate the situation. Rather, enabling legislation like 3DS should be seen as one of three pillars to mitigating chargeback fraud abuse. The second pillar deals with the many technological solutions now being employed. For tech companies like Chargebacks911, Ravelin and Signifyd that are employed by businesses to detect and fight fraud, the name of the game is data — lots of it — to fight chargeback abuse. Such fraud prevention companies incorporate data across its networks of merchants and in some cases even the banks and card issuers to detect patterns of abuse from cards, something the banks alone can’t detect.

“There's lots of ways that friendly fraud expresses itself to the bank. But the bottom line is that the issuing banks don't have any data on the transaction. So they have an inability to add a very detailed understanding what really happened.”

Harlan Hutson, Director of Strategic Partnerships, Chargebacks911

Hutson claims Chargebacks911 to have more consortium transaction data than anyone in the world, even the Big Tech heavyweights. With data from “all the payment brands, all the processors, the CRMs,” Chargebacks911 and other companies like Signfiyd and Ravelin sort with the help of machine learning billions of transactions per month to detect patterns of chargeback fraud.

Source: Chargebacks911

Armed with data and machine learning, companies score all chargebacks from 0 to 100 regarding the likelihood of fraud, with some claims being challenged outright and other users being flagged. Though detecting instances of first-person friendly fraud may be impossible on the front end, big data is utilized to draw clear patterns and reverse fraudulent chargebacks, says Hutson. According to Chargebacks911, its customers win chargeback disputes two or three times as often as companies that dispute chargebacks through internal means only.

Tools at the disposable of merchants also include chargeback alerts from solutions like Visa’s Ethoca Alerts and Verifi’s CDRN. By notifying merchants about pending disputes, it allows merchants to avoid chargebacks by manually providing a refund; such solutions saw a 27% reported reduction in chargebacks, according to Chargebacks911. Major card networks have initiated automated network inquiry programs as well so that issuing banks instantly receive data about the questioned transaction. Such tools require expensive integration, however, which leaves primarily larger companies as the main benefactors.

The newest tool, Visa’s Rapid Dispute Resolution (RDR), allows Visa merchants to set up rules regarding which disputes they’ll automatically accept and refund before it has escalated into a full chargeback. Seeing a 34% reduction in chargebacks, the solution saw 14% of surveyed merchants adopting this method just months after its release.

Beyond data-driven technology, there is also the simple approach of superior customer relations to improve communication and encourage customers to opt for refunds over chargebacks. Basic measures like sending and retaining delivery confirmations, requiring signatures-at-delivery, and keeping photographic evidence of the products delivered and once received, can go a long way in closing loopholes by arming merchants with evidence to dispute fraudulent claims.

A Balancing Act

Yet invariably, chargebacks will happen. How often they do may be culturally influenced — fraud companies note chargebacks happen far more frequently in countries like the UK and the US, where customers feel entitled, than a place like Japan, where such mechanisms are seen as dishonorable — but companies must always strike a balance in deciding which transactions to let through and which to deny.

While companies wish to combat fraud, they don’t wish to unnecessarily increase friction and cost merchants’ conversion rates; this is one complaint merchants have levied against Europe’s 3DS authentication measures. Overly stringent rules threaten the bottom line, while excessively lax rules enable fraudulent chargebacks to run amok. There is also the question of what kinds of products sold are disputed; a company selling high-priced items may apply more friction to the purchasing process and dispute a greater ratio of chargebacks than a company selling low-cost t-shirts that rely on scale.

Source: Chargebacks911

Along with combating criminal fraud, the real question for merchants is whether they will stem the tide of repeat friendly fraudsters. A customer who wins a chargeback dispute is nine times more likely to initiate another one. Especially as channels on Telegram and TikTok teach people how easy it is to initiate chargebacks, companies may not be able to stop most first-time friendly fraudsters, but they must stop fraudsters before the allure of “free stuff” turns a trickle into a tsunami. Whitehead described one client business that came to Signifyd after people on social media spread rumors that customers can claim they never received a delivered item and the business would never check, leading to an explosion of chargeback claims.

While chargebacks occur at a higher rate in the U.S. and U.K., the problem follows wherever cards do; just this month in Africa, Flutterwave’s consumer app had to shut down its virtual dollar card service following a flood of cases of chargeback fraud. As the acceleration of digital commerce attracts more people — including the less tech-savvy — chargebacks are likely to only continue picking up steam — but so will the data-driven tools combatting them. Friendly fraud may exploit the adage “customer knows best,” but in the case of a machine learning program processing billions of transactions over any given month, it just might know a thing or two.

Image courtesy of Jefferson Santos

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Cloud And FinTech: Security Gaps Emerge

Is Alternative Financing Hurting Ride-Hailing Drivers?