Are Some Markets Immune To The X-Pays' Advance?

~6 min read

Apple's recent earnings call grabbed a lot of headlines, and the resulting momentum has nudged the company towards hitting an unprecedented US$1 trillion valuation. Buried a little deeper in the weeds, however, was another significant milestone: in June 2018 Apple Pay processed 1 billion cumulative transactions. While the mobile payment play's growth has been a lot slower than some predicted, it is clear it has put down deep roots and sprouted. Nevertheless, there are still some markets that are proving particularly tough seeds to sow for Apple and its competitor X-Pays.

Onboarding The Banks

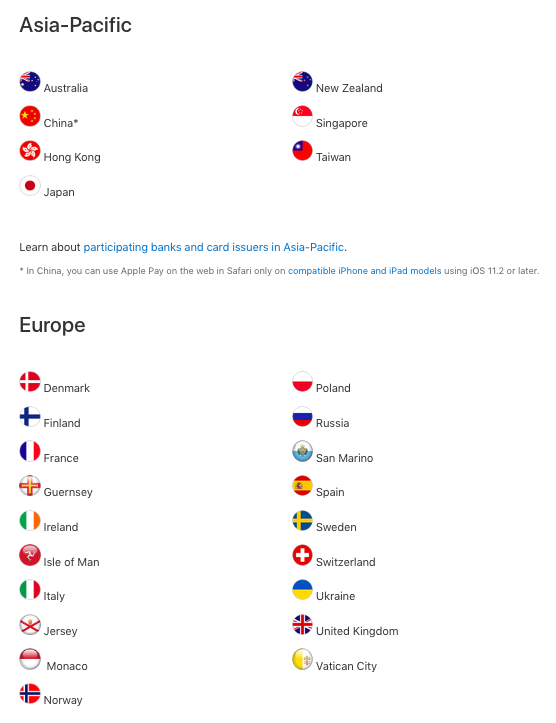

In addition to the U.S., Canada, Brazil, the U.A.E., Apple Pay is currently live across more than two dozen countries in Europe and Asia-Pacific (see the image below). In the context of Apple and other X-Pays, live means having card-issuing banks in that jurisdiction signed up for the service. It is the banks' settlement systems that must be able to recognize the token that represents the mobile device identifier, which the banks are then able to match to a payment card (see here for a previous Mondato Insight explaining how Apple Pay works).

Source: Apple

Obviously, this means that the cooperation of any country's banks, and central bank in all likelihood, is a necessary requirement for Apple and the other X-Pays to function. If, for example, banks decide that Apple Pay is an unwelcome newcomer onto the country's payment scene, then there is very little Apple can do to force its way into consumers' pockets and onto merchants' counter-tops.

This then raises the question why would any banks want to adopt Apple Pay? After all, all Apple Pay does is digitize credit or debit cards issued by a bank and put them on a mobile phone. After that, it is still the banks' payment rails that Apple Pay transactions move on, for which privilege the banks are expected to pay Apple, and not the other way round.

It would appear, then, that this was the very question asked by three of Australia's 'Big Four' banks (National Australia Bank (NAB), Commonwealth Bank (CBA) and Westpac) when Apple Pay came calling Down Under. Given that the country's banks had invested in the contactless payments infrastructure that Apple Pay needed to operate, why should they be forced to open it up to Apple Pay? Particularly, why should they have to let Apple compete with them on their rails when Apple refused to give the banks' access to the iPhone's secure element, thereby denying consumers the choice of which NFC-based digital wallet they wanted to use?

And perhaps most galling for bankers (often used to setting conditions rather than receiving them) Apple stipulates that the fee it extracts from the banks not be passed on to merchants or consumers. From the banks' perspective, these were not, on the face of it, reasonable demands.

Gorillas In The Room

Underpinning this conflict, there also appears to have been a clash of cultures. As a representative of South Africa's Nedbank remarked at the inaugural Mondato Summit Africa in 2014, "MNOs and banks are used to being gorillas in their negotiations." When you put them in a room together, things get interesting (so too, clearly, Apple and Australia's banks). Used to being the biggest kids on the playground, Aussie bankers found themselves sitting across from the biggest kid in the world, who was throwing his weight around. How did the banks' respond? To complain to the teacher, in this case the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

The country's largest bank, ANZ, had already struck a deal with Apple that saw its EFTPOS debit cards launch in Apple Wallets in the the spring of 2016. The remaining three of the big four, along with the smaller Bendigo and Adelaide Bank, sought to get an exemption from the ACCC to band together and negotiate collectively with the Cupertino giant, in order to maximize their leverage. As if to emphasize the banks' discomfort at finding themselves in the weaker bargaining position, among their complaints was Apple's alleged "intransigent, closed and controlling" behavior in attempting to dictate terms to the banks. They also sought permission to enter into a limited and voluntary boycott of Apple while negotiations were ongoing.

Stifling Competition

The banks' arguments received short shrift with the regulator, who concluded in March 2017 that such a maneuver "is likely to reduce or distort competition in a number of markets," including between Apple and Google, as well as in the payment card market. Interestingly, the regulator also had an eye on the wearables market, and was concerned that banks having access to the iPhone's secure unit and NFC transmitter had the potential to allow banks to effectively lock consumers into using phones as payment devices, to the detriment of other players such as Fitbit Pay and Garmin Pay.

This is likely to hamper the innovations that are currently occurring around different devices and technologies or mobile payments.

ACCC Chairman, Rod Sims

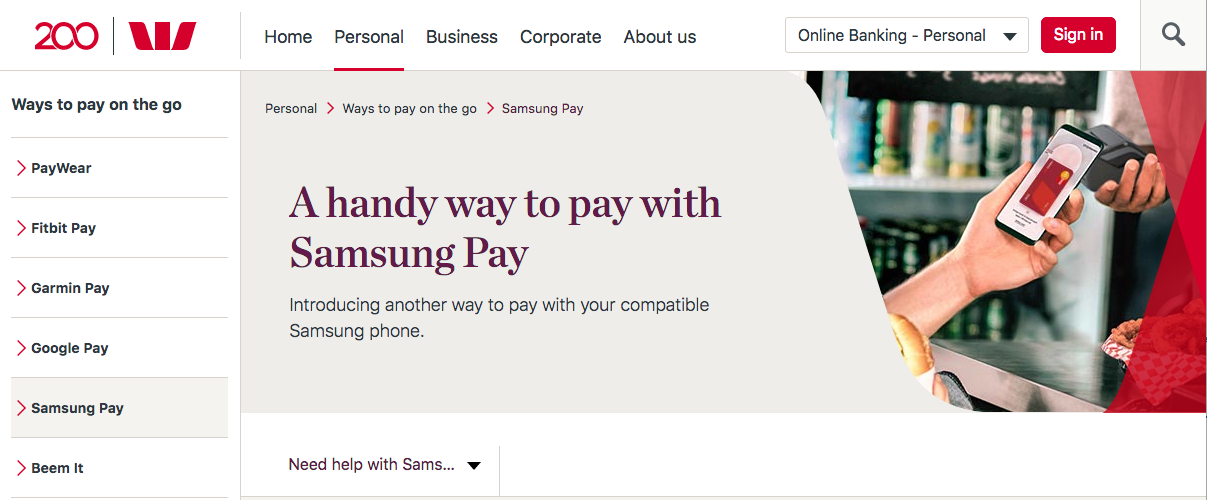

So despite a long list of banks and credit unions in Australia that offer Apple Pay, the four ACCC complainants remain Apple-Pay-free zones. But since late 2016, Westpac, Commonwealth, NAB and Bendingo have all gradually added Samsung Pay to their portfolio of customer digital payment options. It seems, then, that it is pride that is keeping Apple Pay out of the hands of these Australian banks' customers.

Westpac's digital wallet options. Wearable heavy, Apple light.

Silicon Wadi

Israel is another market from which X-Pays have been shut out, due to the peculiarities of the domestic banking and payments markets. Apple Pay's absence is all the more surprising given the presence in the country of the only Apple R&D facility outside of Cupertino, whose 600-strong workforce have been plucked from the country's cadre of tech entrepreneurs, innovators and programmers. Israel's 'Big Four' are even bigger than Australia's, accounting for around 90 percent of the market; the 'Big Two', Hapoalim and Leumi have almost 60 percent of the market just between the two of them, and additionally own two (Isracard and Leumicard) of the three credit card companies that operate in the country.

If that seems to you like overly dominant market positions, then Israel's politicians and regulators tend to agree. Bank Hapoalim and Leumi are being forced to divest themselves of their credit card businesses, which will likely ultimately emerge as competitor banks. In addition, the "Strum reforms" require:

- Obliging the banks to reduce their holdings in the sole domestic card-transactions processor and switch, SHVA, to a maximum of 10 percent; furthermore SHVA will now be permitted to provide services to any person, not only licensed Israeli banks and bank-subsidiaries;

- Obliging Israeli merchant acquirers to host “virtual acquirers” (a concept which is similar to the operations of MVNOs in the mobile communications market), thus lowering the technological barrier to market entry by new merchant acquirers;

- Setting out many measures to help and protect new market entrants, such as an obligation of the banks for a 50 percent reduction in their credit-lines to cardholders in 2021-2024 compared to 2015, prohibition on the banks from approaching their clients in relation to renewal of exiting cards, obliging the banks to offer their clients cards of other issuers, and several other provisions with the goal of establishing a state of competition which will facilitate a broader variety of market players.

So far, so good for payment card competition, you might think.

However, in the context of Tel Aviv's "Silicon Wadi", Israel's banks seem to have sniffed an opportunity to cut the credit card companies and networks out of the payments market altogether. So rather than this tech-savvy country racing to get aboard the X-Pay bandwagon, instead the country's banks have been pushing their own payment apps (and unlike in Australia, without seeking access to the iPhone's NFC hardware). Bit (Bank Hapoalim), Pepper Pay (Bank Leumi), and PayBox (Discount Bank) are, for the moment, P2P or digital banking apps that appear to be designed to build up customer comfort and familiarity. And as Pepper Pay's Q&A states, merchant payments is an aspect of the business they are working on.

And although none of the banks are getting out ahead of themselves right now, it seems likely that it is only a matter of time before one of them, most likely Hapoalim or Leumi, launches a payment service that bears a closer resemblance to Alipay than Apple Pay. With card-issuing "neo-banks" on one side, and the legacy banks potentially going fully digital on the other, an interesting match-up between the world's two predominant mobile payment technologies could be on the cards in Israel.

Banks Will Be Banks

And while one must be cautious about drawing overly strong conclusions about markets as disparate as Israel and Australia, the common thread seems to be overbearing and dominant banks reacting to not getting things their own way, for once. As mobile payments and other wearable payment form factors become part of our daily lives, both of these markets have the potential to present interesting studies into the effects, and limits, of competition between the X-Pays, and between the X-Pays and other players in the mobile payments space.

So while some banks may resist Apple, it seems unlikely that any developed payments market will be able to resist for too long the march of the X-Pays. But banks will always be banks, and it seems likely that where they are dominant, they will, like King Canute, make an attempt to hold back the tide.

Image courtesy of Apple

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Impact Investing: From Microfinance To Fintech

Trade: The Sweet Spot For Commercial Blockchain?