Ethiopia: Time To Do Or Die?

~8 min read

Ethiopia just might be the sleeping fintech giant of East Africa. Aside from being home to a population over 100 million and sharing a border with mobile money powerhouse Kenya, Ethiopia has experienced double-digit GDP percentage growth for years, while low levels of formal financial inclusion create a need for digital payments and transactions. Yet burdensome regulations and inadequate infrastructure have stymied innovation in what has long been one of Africa’s most closed and controlled economies. Despite the hurdles, a budding fintech scene is experiencing consistent growth. With a new regime expressing a desire to liberalize markets and offer greater access to foreign investment, the massive potential of fintech in Ethiopia might finally begin to manifest.

Scenic Mountains And State Monopolies

Since the time of the Derg dictatorship beginning in the 1970s, Ethiopia’s industries have been tightly controlled by state-run monopolies. Despite issues like inflation and a lack of foreign reserves, massive public infrastructure projects since the 2000s have helped GDP grow by double-digit percentage points, year-after-year. However, Ethiopia’s GDP per capita still flounders, ranking 164th in the world according to the IMF.

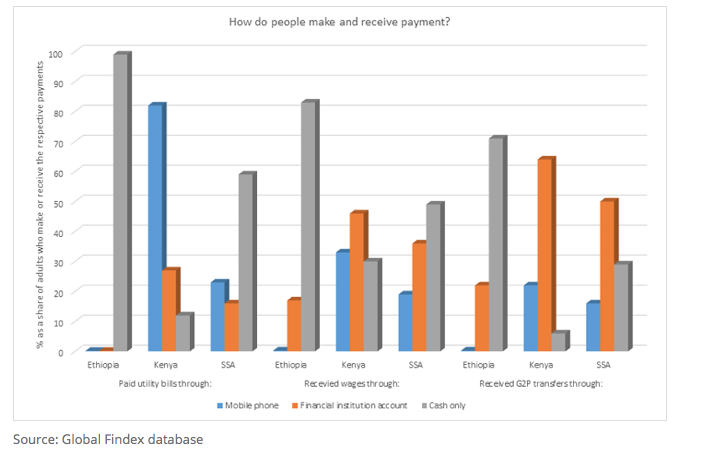

According to the World Bank, financial account ownership increased from 22 to 35 percent between 2014 and 2017, but it’s still low, especially in the rural areas where a majority of the population lives. Though 41 percent of Ethiopians said they borrowed money, only 11 percent borrowed from financial institutions, while 31 percent borrowed from family or friends and another 8 percent from informal savings clubs.

Today, close to 40 million Ethiopians have mobile subscriptions, according to industry insiders — but only about 4 to 5 million have mobile money accounts. Growth has been limited for several reasons. One of the largest issues has been the complete monopoly of the telecommunications industry by Ethio Telcom, the state-owned telecommunications corporation. Despite massive infrastructure projects, Internet penetration in Ethiopia has improved to a meager 15.4 percent of the population. And for those who do have access, the government-run, monopolized services are expensive and quite unreliable, often delivering slow Internet connections. Just last week, Ethiopia suffered a nationwide Internet outage for several days when Ethio Telecom shut down internet access and text messaging. Despite public outcry and international headlines, Ethio Telecom has yet to offer an explanation for the outage.

If Ethiopia's considerable infrastructure and reliability issues weren't enough to dampen growth, governmental regulations have also hindered the efforts of independently-run fintech operations. KYC regulations complicate access, especially for rural consumers. High taxes for ICT companies tighten the margin of error for sustaining a well-equipped digital technology industry, and the country also struggles with a lack of home-grown technical know-how.

Perhaps most significantly, current Ethiopian regulations permit only banks or microfinance institutions (MFIs) to operate mobile money operations. This requires any fintech operator to partner with an approved bank or MFI to perform financial services. With fintechs reliant on Ethio Telecom for mobile service, the lack of service familiarity, reliability and access has made it particularly hard to gain the trust of potential consumers. GSMA’s Mobile Money Regulatory Index, which quantitatively assesses the extent to which regulation has been effective in establishing enabling regulatory environments, ranked Ethiopia 69th out of 81 developing countries.

In this bank-driven model, formal financial institutions have been slow to embrace mobile money services. Because they're shielded from foreign investors by law, banks haven't done much to advance digital services. Mobile money is largely not marketed by banks as a standalone product, but rather as part of a bundle of traditional services, according to Getachew Teklemariam, an Addis Ababa-based investment and development consultant. Coupled with the lack of rural penetration among these big banks, many of the bank-run mobile money services have been dragging in adoption as a result.

“Even now, the electronic banking services are not reliable because Internet infrastructure is not reliable, the demand is not yet there, and our laws are not facilitative for that kind of expansion.” Getachew Teklemariam, Addis Ababa-Based Investment and Development Consultant

In Harsh Mountains, Fintechs Bloom

Despite Ethiopia's inhospitable regulatory framework and patchy infrastructure, fintechs have appeared in recent years and adapted models to the local terrain, strategizing to their individual strengths and weaknesses.

In terms of mobile money, digital technology providers have largely partnered with banks or eligible financial institutions. Last year, the government-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia launched CBE Birr, its mobile money service. Relying on its advantage in resources and formal customers, CBE Birr hopes to compete with the country's established mobile money providers, like Belcash's HelloCash service. Dashen Bank also recently launched the Amole mobile money service, relying on digital technology provided by Moneta Technologies SC. According to Moneta Technologies SC Chief Executive Officer Yemiru Chanyalew, within 11 months of launching, Amole has registered over one million customers and enlisted more than 6000 agents. With a strategy to “win Addis [Ababa] and move to the regional cities,” Amole seeks to offer integrated services in the vein of China’s WeChat, supporting cashless payments, content aggregation, digitized content and online and QR-based commerce.

This urban-focused, app-based push by Amole comes as digital services take root in Addis Ababa and larger cities. Deliver Addis is a digital food delivery service, while RIDE and ZayRide are bringing the Uber model to Ethiopia. But because of low smartphone usage, unreliable service and low mobile money adoption, many of these providers rely on cash and text-based USSD technology for service. Hostile regulations have also been problematic at times for these service providers, one ongoing case being the lawsuit from RIDE, a taxi-hailing mobile service, against the Addis Ababa Transport Authority after they were denied the ability to offer transportation services despite utilizing legally mandated code 3 vehicles.

Due in large part to poor Internet services and restrictive laws, e-commerce has also struggled to coalesce into a mature business-run ecosystem, with Facebook pages and app channels offering a patchwork of commodities instead. Amole hopes that, as adoption increases, it may expand further into these areas.

But whereas scarce infrastructure and poor network penetration have kept many fintech providers from capturing the vast rural populations — 80 to 85 percent of Ethiopia — one mobile money service is utilizing its unique structure there to its advantage. M-Birr launched in 2015, making it the first mobile money deployment in the market.

It is co-owned by six regional MFIs spread around Ethiopia, with Moss ICT providing the digital technology. Utilizing its access to rural networks through its regional MFI co-owners, M-Birr has paced the field in acquiring rural customers. Ethan Laub, Head of Marketing and Product at Moss ICT, estimated that between half and two-thirds of M-Birr’s subscribers live in rural areas. Since only some 15 percent of mobile subscribers have mobile internet, M-Birr relies on USSD technology. Its model has shown progress so far, reaching 1.5 million subscribers and 9000 agents, with a doubling in agents over the last year and 50 percent increase in customers year-over-year.

Though mobile money providers have seen an uptick in merchant adoption in recent months, mom and pop shops have not readily taken to it as a payment option. Consumers are largely using the services to pay back friends and top up their mobile accounts. They can also use mobile money services to pay for DSTV bills, Ethiopian Airlines tickets, ride sharing services and for solar energy from select providers. Most notably, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Finance is using M-Birr to electronically deliver payments to over one million households through its Productive Safety Net Programme, which provides financial assistance to poor Ethiopians — a vast improvement over the previous network of trucks delivering cash to remote areas.

Free Market At The Precipice?

But even given the aforementioned progress, improvements in infrastructure and a more enabling regulatory environment are needed before mobile money and fintech as an industry can truly take off in Ethiopia. A market reform-minded regime took over last year, so optimism on this front has grown. In June of last year, the Ethiopian government announced it will open Ethiopia’s economy up to both Ethiopian and foreign investors, allowing for partial or full privatization of state-owned enterprises, including industrial parks, railway projects, sugar factories, hotels and other manufacturing industries.

It also decided to sell shares of state monopolies like Ethiopian Airlines and Ethio-Telecom. In February of this year, the government issued another proclamation establishing “an independent, transparent and accountable regulatory Authority” aimed at achieving “the government’s policy of restructuring the telecommunications market and introducing competition.” Insiders have also heard rumblings of a new proclamation in the works from the Ministry of Innovation and Technology to promote fintech in Ethiopia.

That is not all. Just this month, the Ethiopian parliament approved a law to open up the telecommunications sector, selling off 30 to 40 percent of shares of Ethio Telecom to the private sector — including foreign bidders. Officials are saying it should be done by the end of the year, and multinational telcos like Safaricom, MTN Group, Vodafone and Orange are reportedly chomping at the bit to buy into Ethiopia’s potentially gigantic telecommunications market. The entry of such telco behemoths has the potential to greatly accelerate competition and overhaul the Ethiopian market.

“If they come, it would be really helpful in at least them sharing experience, ensuring the banks improve services and applying their resources. There is more hope in the coming years.” Getachew Teklemariam, Addis Ababa-based Investment and Development Consultant

But despite these promising signs, regulatory reforms have yet to take place. Laub described the industry as being stuck in a “wait and see” stage, preparing for whatever reforms are actually implemented — or bracing for liftoff if Ethiopia decides to move away from the bank-driven model of mobile money services.

One of the biggest areas of service M-Birr sees potential in is the development of additional use cases for mobile money customers — like paying recurrent bills, for instance. Though Moss ICT has worked closely with financial institutions to introduce bill payment options, government-owned utilities must allow those payments to be made electronically. Foreign remittances are another area only traditional banking services can operate in, with CBE Birr managing to launch the first Ethiopian international mobile money transfer service this year.

“The relatively new government seems to really want to institute reforms and encourage modernization and investment. But we know that things can slow down, it may take time to implement, and there are still risks that [reforms] can be blocked by existing interests.” Ethan Laub, Moss ICT Head of Marketing and Product

As evidenced by foreign telcos’ eagerness to enter the scene, the Ethiopian digital market might be on the precipice of transformation. The number of mobile money subscribers (between 4 and 5 million) in Ethiopia is dwarfed by the country's population (110 milion); the country is home to 60 million adults and approximately 40 million mobile subscribers, which suggests that increased competition and loosened regulations could do wonders for both mobile money and the wider fintech apparatus, possibly even spurring much-needed improvements in infrastructure and network reliability. M-Birr envisions a quintupling of agents to handle a future Ethiopia that approaches levels of financial inclusion closer to those of neighboring Kenya.

The new government’s rhetoric suggests they share such a vision, too. With the auctioning of Ethio Telecom shares, the first shoe drops. It’s still not clear exactly when or what reforms will be made, however. Internet services need to expand greatly and quickly enough to facilitate fintech growth and ubiquity. And consumers need to trust telcos — previously unfamiliar, unreliable and inaccessible — to start handling their money. These hurdles may determine how quickly fintech ascends in Ethiopia — but suddenly, its rugged mountaintop doesn’t look so impossible to climb.

Image courtesy Gerald Schömbs

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Climate Change: Macro And Micro Resilience

Paytm: Are One Billion Credit Cards Coming To Asia?