Islamic Fintech: An Ethical Financial Inclusion Proposition

~10 min read

Islamic fintech signifies far more than technological updates to traditional Islamic finance. The industry is grounded by traditional principles strikingly in line with the stated ideals of the fintech revolution, yet with the proper guardrails conceptually to ward off the sector’s worst vices. This isn’t about faith, but logic.

Islamic or sharia-compliant finance — a wide, complex field comprised of a phalanx of laws and advisory boards — at its core requires financing to be based on real economy sector businesses instead of purely moneymaking transaction endeavors. Interest-based debt is haram, or forbidden — traditionally tossed aside in favor of alternative models like risk-sharing. Zakat, an effective 2.5 percent wealth tax utilized in reducing poverty, amounts to about US$600 billion a year serving fintech’s blind spots at the bottom of the pyramid, buttressed by a deeply community-oriented approach that NGOs only wish they could replicate from the outside.

The tantalizing intrigue of combining new age technologies with centuries-old financing practices flows in both directions. On the one hand, emerging technology like blockchain can revolutionize shari’a-compliant processes borne of analog times with tools seemingly custom-made for the system’s vast complexities and transparency requirements. At the same time, ethical principles calling for responsible, non-exploitative investment and financing options guide the outlook and characteristics of the emerging fintechs from this space. Islamic fintech’s fusion of old and new is already creating unique permutations of enterprise and social impact in its very early stages. Attracting both the voluntarily and involuntarily unbanked, the Islamic fintech industry will financially include populations that can’t be otherwise reached — and through ardently financially healthy means.

An Update, A Remix — Or Something New?

Islamic Fintech’s potential as a tool for financial inclusion is obvious. As discussed in a previous Mondato Insight published last month, there is a particular lack of financial inclusion in the Middle East region considering its relatively high mobile adoption rates, and the case holds true for Muslim countries in general. While 92 percent of people in high-income countries are financially included, that number falls to 41 percent among member countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, according to the 2017 Global Findex Database. Religion is cited as the factor for not having an account by 5 percent more people in OIC countries compared to elsewhere — a figure that when extrapolated to the global Muslim population comes out to over 100 million people who are voluntarily excluded from the financial system. Comprising over half of the global population under 34 years old, the global Muslim population is quite young and digitally savvy, too, making them particularly apt for financial inclusion through digital means.

Source: World Bank

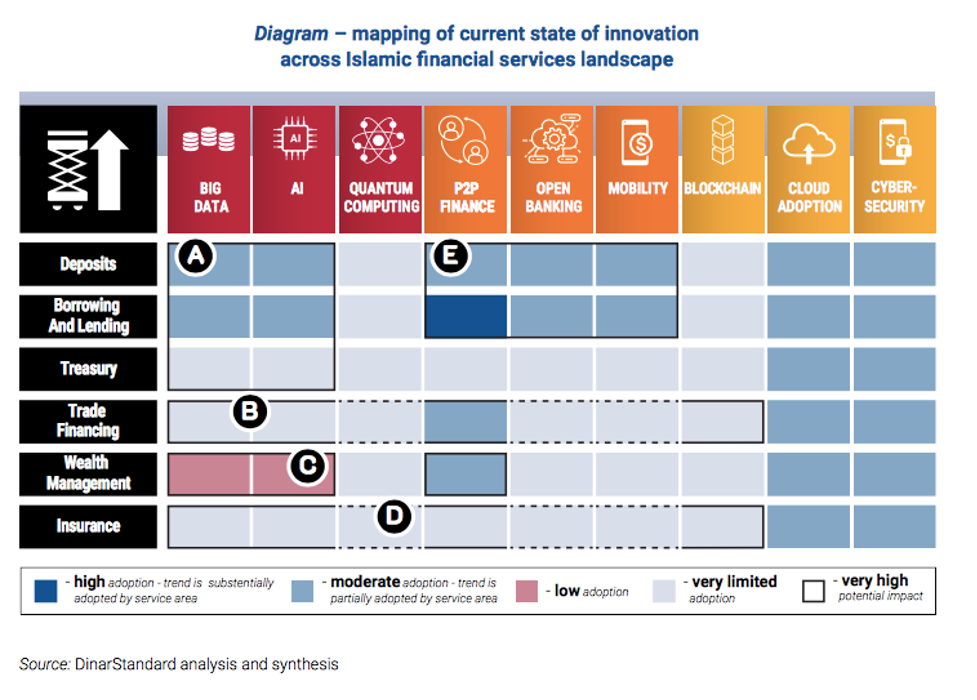

Regulations and a lack of licensing delayed the sector’s birth and early growth, with activity only picking up in the past few years, but digital financial models like Islamic robo-advisors and challenger banks are developing to serve and expand the parallel ecosystem that Islamic finance built over hundreds of years. A potentially fluid relationship between mainstream and Islamic fintech is best exemplified with emerging insurtech. Takaful-tech digitizes takaful, or Islamic insurance, which calls for a cooperative system of resource pooling to make payouts to members facing a loss of any kind, with excess savings repaid back to members. While its modernized version has made limited inroads so far with a lack of capital and outdated regulations slowing its early development, the possibilities for Islamic insurtech technologies are already exhibited through mainstream channels like insurtech leader Lemonade.

“Lemonade pools some kind of reserve fund in different ways, and then when there is an excess it is given back. That is basically what takaful is, which existed for like 1500 years. It’s just that in the modern context, modern insurance is very difficult to implement through takaful. When insurtech came along, however, based on logic — not Islamic principles — Lemonade came out. There are a lot of financial concepts that haven’t seen the light of day because the previous financial system was too rigid. In fintech today, those ideas can come out."

Umar Munshi, Co-founder & Managing Director, Ethis Ventures

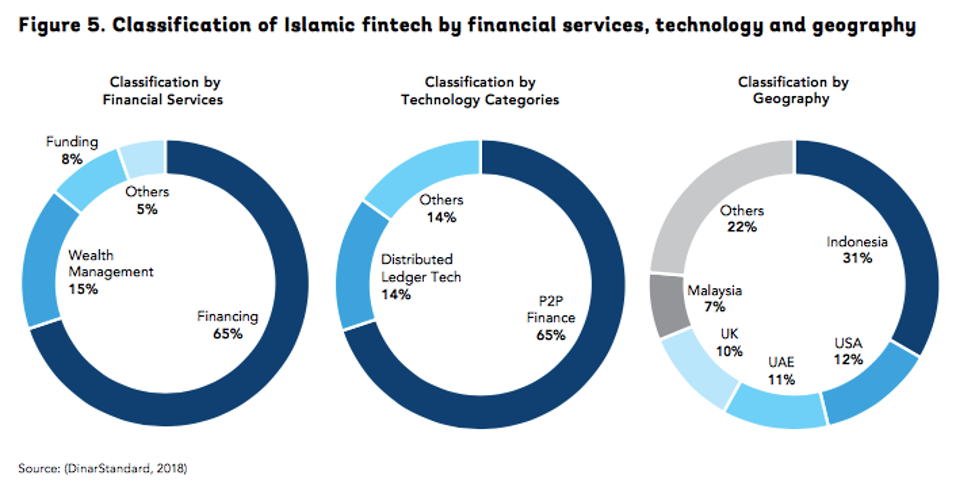

While takaful-tech promises strong gains in the future — traditional takaful activity alone accounted for US$46 billion in 2018 — early activity in Islamic Fintech has centered around peer-to-peer financing and crowdfunding. According to DinarStandard, of the 93 Islamic fintech companies it counted in 2018, 65 of them were P2P financing companies. P2P financing perfectly embodies the Islamic financial ethos: it is participatory rather than passive, it often shares risk among investors and entrepreneurs alike, and it naturally gives way to social finance endeavors in the spirit of sadaqa, or charity. The emerging P2P space is introducing financial solutions in which technology impacts Islamic finance — and Islamic finance impacts the tech applications.

A Revamping and a Rebranding

Southeast Asia and Indonesia in particular has seen much of the early Islamic fintech activity. Indonesia, with a population of 270 million, of whom nearly 87 percent are Muslim, has seen marked fintech acceleration in recent years buoyed by a proactive government, high mobile penetration and the inherent need for alternative financial solutions in a country comprised of thousands of islands. While the Islamic fintech sector in Indonesia is dwarfed by conventional digital lenders — who often rely on predatory techniques and interest rates as high as 1 percent a day — one third of all early Islamic fintech companies were found in Indonesia, according to DinarStandard.

These early-stage companies often take traditional community practices or organizations and imbue them with the efficiencies and transparencies that technological tools offer. Blossom Finance doesn’t do any direct lending or investing. Rather, they provide capital, software and financial products to veteran Islamic microfinance cooperatives embedded within local communities. By digitizing small local banks with long communal ties and providing them digital platforms, Blossom enables expanded financial inclusion in communities that are otherwise wary of or lacking access to larger financial institutions. In the traditions of Islamic finance, Blossom is only compensated if investors make money.

“You need local experts on the ground to ensure that the money is being used productively, to ensure that the money overall is going to help a business grow, is going to help a family and not make them poorer. The worst thing you can do is take someone who’s poor with zero debt and then keep them poor but give them debt. So we believe this sort of last-mile coverage is really, really critical, and that’s why our model works specifically with these cooperatives.”

Matthew Martin, Founder & CEO, Blossom Finance

Blossom’s digital work with small community banks strengthens the ability for such licensed cooperatives to employ a mix of social funds with commercial funds to target all the socioeconomic levels in need of financial tools or assistance. This serves as a digital update to the Islamic model that in Indonesia is called Baitul Maal Wat Tamwil (BMT), or a house with two sides: a commercial house and a charitable house. At the bottom of the pyramid, social charity funds — with its fundraising and distribution processes now digitized by Blossom — offer people the help needed to rise up the economic ladder and begin productive economic endeavors. Qard al-hasan, or interest-free loans, benevolently target those at the next-lowest rung of the socioeconomic ladder in helping them begin small enterprises, after which successful small businesses can reach the economic level to take on greater investment initiatives that eschew debt-based financing.

Blossom has also pioneered in recent years so-called Smart Sukuk. Sukuk are capital market instruments serving as alternatives to traditional financing bonds. The complex processes underlying sukuk may ring up accounting costs alone of over US$100,000, according to Blossom’s Martin, typically rendering sukuk only accessible to governments or large corporations. Smart Sukuk seeks to democratize the process by utilizing blockchain.

Source: World Bank

Considering the intensely complicated transactions processes involved and the burdensome rules-based system to follow, there was tremendous early interest in how blockchain can be utilized to bring efficiency and transparency to Islamic financial systems that otherwise elicited higher risk and higher costs compared to conventional models. In the case of Smart Sukuk, the idea is to utilize blockchain to eliminate the middleman accounting practices ensuring shari’a compliance that have made sukuk a financially untenable proposition for smaller businesses. Adoption of Smart Sukuk has been slow especially during the pandemic with government subsidies flush, and blockchain’s hype in the wider space has diminished in the past couple years as companies grapple with the need for scale to make the transparency and traceability value propositions work. But blockchain instruments like Smart Sukuk make it possible to democratize financial instruments over the next several years that the fundamentals of an earlier economic age simply couldn’t muster.

If Blossom layers technology above long-held Islamic practices with an orientation towards inclusion, Ethis Ventures applies those Islamic tenets to conventional Fintech models. Rather than solely focusing inward and transforming the Islamic financing landscape, Ethis believes it can have mainstream impact with inspiration from Islamic financial tenets. In the decades leading up to the fintech revolution, Islamic finance faced criticism for increasingly utilizing processional workarounds that mimic conventional, debt-based financing models. But as digital tools smooth over the previous efficiency gaps between Islamic and conventional systems, ethics-based financing re-emerges to become a unique value proposition in the chaotic modern arenas of lending and crowdfunding.

“When we started, we were initially very gung-ho and maybe idealistic about Islamic finance as good for humanity, good for everyone. But over time we toned down our branding and focused on the brand itself. Not Ethis being Islamic, not having Islamic as our top-line identity, but instead being ethical and impactful.”

Umar Munshi, Co-founder & Managing Director, Ethis Ventures

This branding shift towards “ethical” or “responsible” financing doubles down on the belief that the model can affect positive, inclusive change on a wider scale in populations Muslim or otherwise. Ethis doesn’t stray far from traditional crowdfunding platforms, but it’s uniquely driven by the underlying values of justice and fairness. Ethis is a group of platforms focused on matching funds from donors, investors, and contributors to fund campaigns and projects, focusing on sustainable and impactful financing ranging from charity to equity-based investment. Ethis holds a P2P financing license in Indonesia and launched the first shari'a-compliant equity crowdfunding license in Malaysia in 2020. It is also making inroads to operate regulated platforms in other regions including the Middle East. Though originally focused on real estate crowdfunding, Ethis successfully shifted its priorities during the pandemic towards SME funding to fill the lending gap created by risk-averse banks — exhibiting the classic nimbleness of fintech startups.

Onward and Ethical Upward

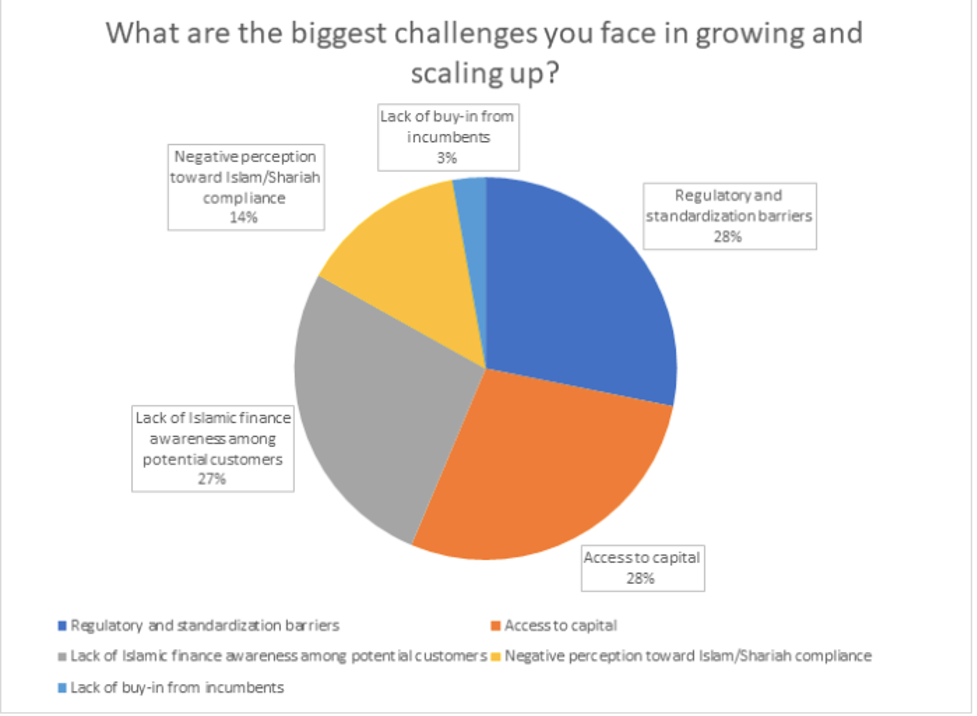

Although the early-stage Islamic fintech sector is seeing healthy growth, it is doing so from a very small market share. Regulators so far have prioritized licensing conventional fintechs over shari’a-compliant fintechs, slowing the growth and maturation of the sectors. B2C Islamic consumer activities remain heavily regulated in key regions like the Persian Gulf region, and for now Islamic fintechs are unable to hold deposits for Islamic-oriented consumers like Islamic banks already do.

Source: IFN Fintech Survey 2020

Along with regulations, the other most significant hurdle for Islamic fintechs has been the lack of sharia-compliant VC options up to this point. But when considering the potential market size of hundreds of millions unbanked in areas with young, digitally savvy populations — and the global Islamic economy projected to reach US$2.4 trillion by 2024 — growing fintech hubs in places like the UK, Malaysia, the UAE, and Bahrain are jockeying to lead future Islamic fintech powerhouses. Dubai’s DIFC Fintech Hive has devoted much of 2017’s US$100 million dollar Fintech Fund to incubating and accelerating Islamic fintech companies, in the process becoming one of the early leaders in the sector. With support from the government and partnering with entities like the Islamic Economic Development Center, DIFC is intent on positioning Dubai as the capital of the Islamic economy, according to Raja Al Mazrouei, EVP of DIFC’s Fintech Hive. DIFC is working with Islamic financial institutions to integrate them with fintech startups. These efforts from government-backed fintech hubs — with their connections, capital, and state mandates — position the sector to take off in the coming years once regulations catch up and the space matures.

“You are at the point where you are shaping the regulation, you are understanding the matter, complying with the requirements, which will then increase the credibility of these legislations or regulatory environments. It’s organic, it’s a bit slow now, but once it’s more evolved, we will be able to drive both the demand and the supply for such solutions.”

Raja Al Mazrouei - Executive Vice President, DIFC Fintech Hive

Intent on fulfilling the sector’s untapped B2C potential, DIFC’s Fintech Accelerator Program has cultivated startups like Saudi-based Hakbah, a cooperative savings app which automates traditional communal savings process under the kingdom’s regulatory sandbox and has recently partnered with Visa to issue prepaid cards to customers.

But transformation won’t happen overnight in this painfully young sector even with this high-level support. In Indonesia, Islamic fintech still only accounts for a tiny fraction of the country’s lending-heavy fintech space, maybe a couple percentage points or so of the whole pie. With year-to-year growth rates primed to accelerate as regulations and licensing progress, Ethis’ Munshi envisions Islamic fintech’s market rate in Indonesia reaching 20-30 percent of the total share in the next five years or so. But the sector is still too young to really gauge in number terms what the impact trajectory will be.

Whatever that trajectory may be, Islamic fintech will obviously not be a panacea for financial exclusion and irresponsible lending alone. But it offers a compelling option at all levels of society — including the bottom of the pyramid — that conventional fintech has sometimes fallen short of. Cross-border and financially inclusive yet grounded in high-minded principals, Islamic fintech will embody the shared ideals of Islamic financing and fintech to optimize the best of both worlds — old and new.

Image courtesy of Artur Aldyrkhano

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

PayPal’s Indian Exit and Chinese Entry: Why?

Is Covid the “Big Bang” of Digital Payments?