Israel: Can Sentiment Alter A Tech Sector’s Trajectory?

~9 min read

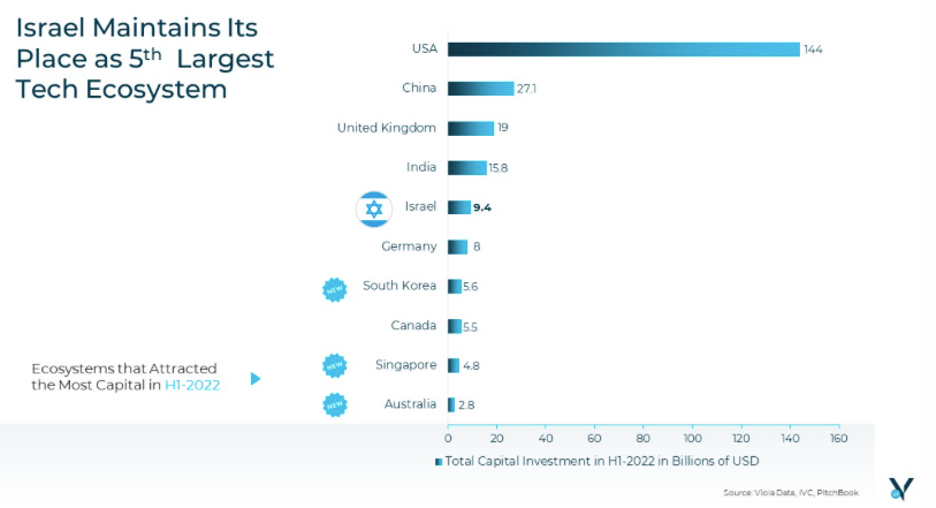

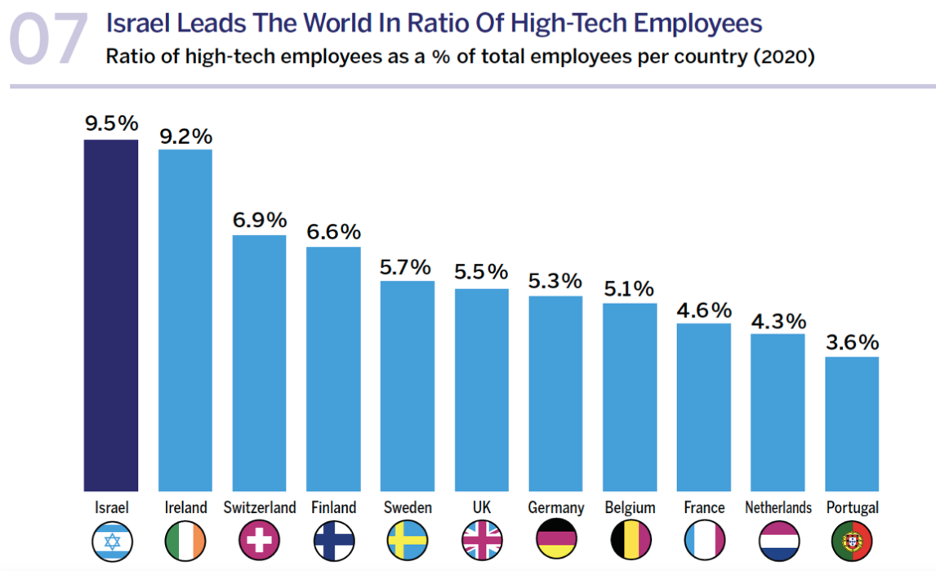

With the “Start-up Nation” brand and all, Israel punches far above its weight when it comes to tech. Yet the Israeli government’s new proposals to overhaul its judiciary system is leading some to proclaim Israel’s status as both a liberal democracy and — consequently — a leading tech sector to be in danger. There is little agreement across the Israeli political spectrum what effect these proposals will have, and even less so regarding Israel’s tech sector. The developing situation raises larger questions both tangible and intangible in nature, among them the role liberal democracy plays in cultivating and maintaining a thriving tech ecosystem. Studies and examples elsewhere suggest such links aren’t completely straightforward, but sentiments and perceptions — as nebulous as they may be — can and do shape reality, if among a variety of important factors to consider.

A Jolt Of Uncertainty

The Israeli government’s proposals are still being voted on, with ongoing discussions most recently involving a slightly watered down compromise that’s criticized by the opposition as providing only cosmetic changes. But along with a host of other proposed changes, the ruling coalition is seeking to strip Israel’s Supreme Court of its ability to overturn laws passed by the unicameral legislature while empowering the legislature to make judicial appointments.

These proposals have spurred massive demonstrations since January, with up to 500,000 Israelis, or 5% of the country’s population, coming out to protests. Banners and signs across these protests cry out to “Save Our Startup Nation,” and the potential effects on Israel’s tech sector has taken center stage.

Source: Viola Ventures

As the proposals continue to wind their way through the legislative process, the tech impact so far has largely been financial. At least $1.5 billion to $4 billion in deposits have been taken out of the country, including at least hundreds of millions of dollars from tech companies. Though some of these exits are in essence political statements, others are resulting from fears of wider economic instability. This capital outflow has resulted in the shekel weakening significantly since the reform began, with the Israeli shekel falling as much as 10% compared to the U.S. dollar.

In the preceding months, the proposals have led to scores of Israeli economists, along with former leaders and the current governor of the Bank of Israel, warning of economic calamity if the reforms are passed as proposed.

As Michel Strawczynski, an economics professor at Hebrew University and until December a director of research at the Bank of Israel, describes, the Israeli economy, by other indications, is quite strong: high economic growth, low unemployment, lower inflation compared to other countries, and even the government budget has a surplus for the first time in nearly 40 years. The capital flight and currency devaluation so far is fear-driven. Even if they are grounded in nothing substantive so far, such fears can turn into panic, and a self-fulfilling prophecy commences.

Many factors go into the success of any tech sector, among them regulation, education, human capital, investment levels, and demographics, which largely remain consistent among countries in a short time span. Yet in the case possibly unfolding in Israel, the intangibles, while hard to define, may ultimately have a significant impact on some of these primary ecosystem variables.

“Do I think that the worst-case scenario is imminent? No. But what I can absolutely speak to is the perception, which is extremely real. And it's not just a perception; it's the viewpoint of many people that this is a clear and present danger to the sector.”

Jack Levy, Founding Partner, More VC

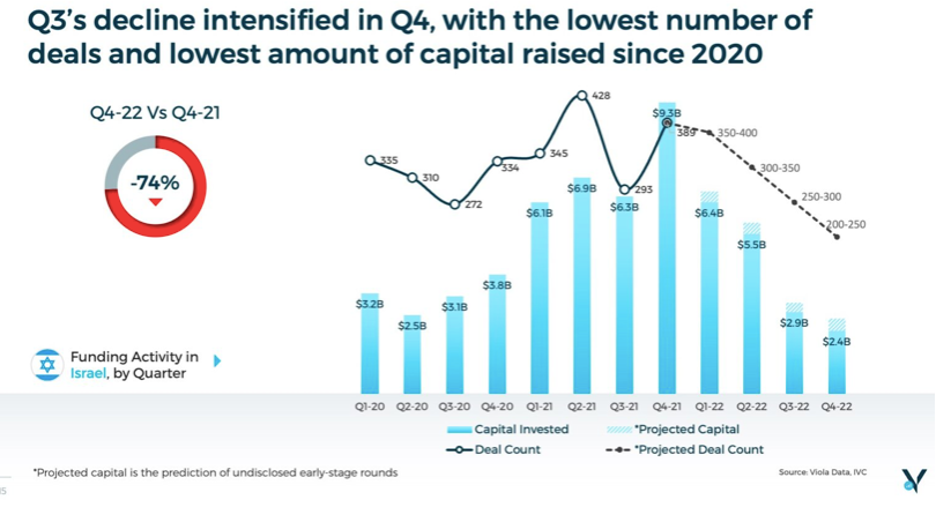

What danger this really poses to Israeli tech encompasses several areas, though figures within the industry emphasize different concerns — or no concerns at all. In the eyes of Nir Netzer, founding partner at Equitech Financial Consulting and chairman of the Israeli Fintech Association, the greatest threat is in the area of investments. Even before the proposed judicial overhaul, Israeli tech companies had seen investments dry up in 2022 along with the rest of the world.

Source: Viola Ventures

In this developing situation, Netzer places foreign investors of Israeli tech into two groups. In the first group are those who are most familiar with the Israeli tech sector’s perseverance through regional turbulence over the years. Largely, they view these developments as merely another blip on the Israeli radar. The second group of investors are those with shallower links to Israeli tech. Perceiving the developing situation from the perspective of sheer instability, these investors are suddenly looking elsewhere at least for now. Those within the sector speculate this has slowed foreign investments greatly — and at a fraught time for Israeli tech.

“These companies that didn't raise [funds] for the last year or so, they're now choking. If they won't raise [funds] by mid-2023, they will die… Every year, about 75% of investments in Israeli tech is coming from foreign investors. We’re dependent on those foreign investors. And if they won't come, this means trouble.”

Nir Netzer, Chairman, Israeli Fintech Association, and Founding Partner, Equitech Group

This pause in funding is not absolute, and Netzer believes the wider positive externalities of Israeli tech will ultimately persevere. Ziv Cohen, CEO of Israeli cybersecurity fintech Paygilant, believes much of the dire warnings regarding the impact these proposed reforms will have on Israeli tech are more politically motivated than based on grounded assessments. Having recently kicked off another funding round, no investors he's spoken with said they won’t invest in Paygilant because of the developing situation.

“At the end of the day, the brains are still here, the knowledge is here, the innovation is here. This will keep producing tons of money for investors. So maybe in the very short term, we might see cases where investors [take out their money]. But, looking mid-term, I think that once everything gets back to normal, and I believe that it will, you'll see money flowing back to Israel.”

Ziv Cohen, CEO, Paygilant

Mind Over Matter

If the reforms are passed, however, it may be difficult to fully measure its impact on the tech sector. Strawczynski is among the signatories of letters from economists warning of disaster these reforms will bring to Israel’s economy and tech sector. Strawczynski and his colleagues cite studies from scholars like Harvard’s Andrei Schleifer claiming that the concentration of power without proper checks and balances in a government can significantly reduce the GDP growth of a country. While Strawczynski doesn’t envision as dramatic an economic shift in Israel’s case as may be evident in repressive autocracies, he believes Israel’s status as a tech leader would be imperiled particularly when it comes to future growth.

“I do not believe existing firms will change their location. It's not logical because Israel is a very strong country, with strong externalities, very strong engineers. But new firms, and we have thousands of new firms every year, they may say, okay, I'm not sure whether property rights will be defended here — maybe we'll go to another place.”

Michel Strawczynski, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Hebrew University

What may emerge — at this point on a purely theoretical basis — is impact on Israeli tech unfolding in two stages: the immediate term, when the capital flight experienced to a small degree so far accelerates if these reforms are actually passed, and on a longer timeline diminished financing and a lack of entrepreneurial replenishment to Israel’s tech ecosystem contributing to a more general brain drain.

Source: Israel Innovation Authority

Dealing in sentiments and fears, the scale of such potential impact is not so black and white. Impact may vary parallel to whichever elements of Israeli tech being discussed. In Israel, much of its entrepreneurs and workforce first developed their skills in the cyber units of the Israeli military. Firms bolster and utilize Israel’s “Startup Nation” brand for instant credibility; the national and private sector interest, to a large degree, becomes intertwined.

“I’m not going to do anything that will damage my country. My country is me, my family, my people. I'm not going to do that.”

Ziv Cohen, CEO, Paygilant

Yet Israel’s status as a global tech leader both reinforces and is perpetuated by its ability to attract money and talent from afar. With tech talent in demand across the world, the mobility of tech workers can be a boon for a thriving tech sector, yet the bane of a society wracked with instability. Brain drain can happen quickly.

Julia moved to Israel shortly after the election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, seeking a better health care system as well as a stable liberal democracy and economy. Now working at Payoneer, a leading Israeli fintech company, she is preparing to leave Israel if the judicial reforms are passed. Fearing that a plummeting shekel will wipe out her retirement savings, she is eyeing the many opportunities her, and her American partner would find elsewhere.

“I've never had a mission to be here forever. But now with this we can go to New York, we can go to Brazil, we can go somewhere else. There's no need for us to be here if things keep getting worse.”

Julia, Payoneer employee

Hungary For FDI

In parsing what kinds of impact such political changes may have on Israel’s tech sector, there is no apples-to-apples comparison with another country. No tech sector leader as advanced as Israel’s has experienced democratic backsliding. But strained comparisons can be made. In a more extreme comparison, Belarus’ tech sector has been decimated as a result of deepening political repression, with a recent Rest Of World report describing how 78% of startup founders and 20,000 tech workers out of an original 60,000- to 100,000-person workforce have left the country since 2020.

Strawczynski prefers to draw comparisons with Poland and Hungary, which saw similar efforts to strip judicial independence and oversight. There wasn’t anything like the exodus experienced by Belarus, with the tech sector remaining a vital component of their economies. A place like Poland remains an attractive, cheap avenue in areas such as startups and outsourcing. Both countries retain strong sources of tech talent.

Yet there are indicators that the countries are not living up to their tech potential. Strawczynski spoke with an official at Hungary’s Central Bank who noted that since the democratic backsliding, the country’s tech sector has done worse, with Hungary standing out as the only East European country without a single unicorn.

An argument can be made that such turns towards illiberal democracy may not demolish a tech sector altogether, but it can limit its ceiling. Both Hungary and Poland’s tech sectors lag greatly when it comes to foreign investment, greatly relying instead on government sources of funding, with upwards of 80% of funding coming from such domestic sources — a near reversal from Israel’s situation. The Hungarian and Polish economies have also underperformed compared to their EU peers, with Hungary slipping into technical recession twice in the past three years and Poland experiencing the worst GDP growth in Q4 of 2022 among Central and Eastern European countries at -2.4%.

Israel’s Globes recently did a deep dive on Poland’s tech sector following its own judicial reform, chronicling instances in which arrest and intimidation of entrepreneurs who voiced differences with the government’s political stances. This has compelled some investors in Polish startups to engage with Polish companies that will only expand operations and retain their IP outside the country. Without proper checks and balances from the government, a business’ interests can’t be guaranteed.

“It's not always possible to show causality, but it's quite clear that if there is such a fear around, you get hurt.”

Michel Strawczynski, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, Hebrew University

Separating The Leaders From The Pack?

At this juncture, drawing such comparisons and making inferences to Israel’s situation is purely theoretical. These reforms haven’t even been made law yet, with compromise of some sort likely and true effects on Israel and its tech sector yet to be determined. Israel as a tech sector is further along than Hungary’s or Poland’s ever was. On the flip side, cases like Singapore suggest a country can be a global leader in business while possessing a government without liberal democracy — though Singapore also utilizes independent Western-style arbitration mechanisms to assure business disputes are handled without interference from political interference. Even looking at Africa, some of tech’s greatest success stories like Rwanda and, most recently, Ethiopia, have come in places where healthy liberal democracy remains elusive, yet markets are liberalized. To say that political systems are the end-all-be-all for a tech sector’s fate would be foolhardy.

Yet none of those other examples are tech leaders like Israel. The leading autocratic country when it comes to tech, China, has seen its sector recently struggle because of government interference. Israel’s potential situation is not nearly the same, but these attributes fall along different points of a spectrum — not a separate paradigm altogether.

Numerous factors go into the success and breadth of a given country’s tech sector: demographics, education, economics, human and financial capital, and so on. None of these advantages of Israel changes with these proposals; the fundamentals remain strong. But if instability or even the perception of it takes hold, then investors, entrepreneurs and tech talent can react with their money and feet, and those fundamentals can diminish at least somewhat.

A lack of liberal democracy may not be enough to stem the tide of ascendent fintech hubs in places like Rwanda or Nigeria; if anything, tech can be construed in such contexts as an economic lifeline for emerging markets promoting opportunities, inclusion and even representation. A narrative of economic ascendence is far easier to get behind than one of polarizing political transformation. To become and remain a true global tech leader attracting the finest talent and largest funding rounds, however, Israel may prove that the calculus is different.

Image courtesy of Shai Pal

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Regulation: Time to Ask for Permission And Not Forgiveness

Where Refugee Fintech Falls Short