The Last Mile: Mobile Money Agents

~7 min read

Mobile money agents - frequently described as the “bridges” to financial inclusion - constitute the last-mile distribution network of digital money services. These fleets of financial mediators are rapidly growing in size and complexity, and the successful integration of new technologies and best practices in managing them will only increase in importance as the universalizing effects of interoperability collide with the competitive advantages of ‘culturalization.’ With only a year and a half to go until the universal financial inclusion goal of 2020, what opportunities are there for mobile money providers - through strategic investments in agent networks - to conquer the last frontiers beyond mobile money’s reach?

Break The Network

Mobile money continues to grow at breakneck speed in emerging markets, creating a patchwork of corridors connecting the rural to the urban - and the Global South to the North. Formal account ownership of a mobile money account has been responsible for a sizeable chunk of the inroads made into the World Bank’s goal of 100 percent financial inclusion by 2020, particularly in Africa where mobile money growth has accounted for nearly all of the growth in formal account ownership in recent years. In setting their sights on an additional 1.7 billion globally (the number of adults worldwide without a formal account of some kind), mobile money operators rely on a complex and fast growing network of agents who are in many cases the forces driving account registrations as well as ensuring the smooth execution of transactions.

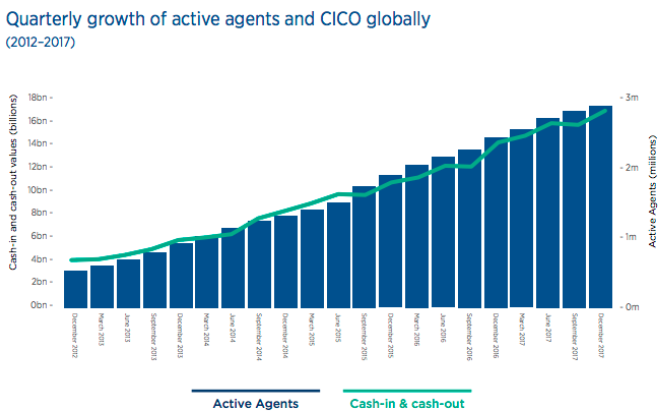

‘Fast-growing’ is no exaggeration: the number of mobile money agents grew more than 10x in less than a decade, topping 5 million in 2017. At the crux of sustainably scaling such a formidable collection of networks is, first and foremost, the profitability calculus for agents, as well as the streamlined delivery of support and responsiveness needed for agents to perform their critical functions at the last-mile of the digital money pipeline.

Nurturing an effective agent network is no mean feat for mobile money operators who face a number of challenges, from regulatory hurdles to building and retaining consumer trust, in staying afloat (a reported 80-90 perfent mobile money companies fail). Keeping agents happy is no cakewalk either - even in Zimbabwe, where one might assume mobile money’s particular ubiquity would signal a happy mobile money ecosystem, agents face serious challenges in managing reserves of hard cash, and are often forced to establish multiple-tiered pricing and black-market markups to deliver the critical cash-in / cash-out functions (CICO) that make up the bread and butter of their mobile money toil.

101 to 2.0

For the mobile money operators that do intend on surviving, different strategies have emerged. In Senegal, where traditional telcos were slow to the starting gates in deploying mobile money networks, dedicated mobile money operators like Wari and Joni Joni have leapt to dominance. Here, most agents are not bound by exclusivity agreements in offering mobile money services to their clients as in bank or MNO-dominated mobile money landscapes like Kenya, India and Indonesia. Variation in the preponderance of exclusivity across countries is quite high - sometimes determined by regulation, as in Senegal - and has been associated with up to 40 percent higher revenues for agents in countries like Senegal, Kenya and Bangladesh.

Aside from this exclusivity, a mobile money network may be composed of dedicated agents whose digital finance services constitute their full-time occupation, non-dedicated agents who are typically retail merchants of all stripes, from kiosk sellers to gas station attendants, or a combination of both. While the up-front cost of recruiting and continually training dedicated agents is often higher than opting for the more franchise-leaning model of non-dedicated agents, getting the incentive structure right across the diversity of the latter is a tricky proposition, particularly in an industry where agent remuneration from CICO accounts for more than half of total provider revenues.

This has put pressure on providers to distinguish themselves from one another through branding differentiation and innovation. Witness Wari’s aggressive and innovative expansion plans: after being burned by a retracted offer to be bought by Tigo, a competitor and local division of Swiss telecom behemoth Millicom, Wari joined forces with a French billionaire-led consortium and has recently announced partnerships to integrate its digital wallet services into both Whatsapp and Mara Phones (French), a ‘made-in-Africa’ handset manufacturer based in Rwanda.

Indian payment providers, for their part, are getting the governmental green light to push the reach of their agent networks further into the remote markets that remain uncharted territories for digital money’s reach: the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently published a comprehensive payments vision document and drafted rules for a regulatory sandbox that fintech companies can use in targeting the Tier 2 and Tier 3 markets from which “a healthy share” of the next phase of growth for the Indian digital payments ecosystem will come.

Agents, Are You Happy Now?

As mentioned previously, one of the key ingredients to successfully managing agent network growth lies in keeping agents’ operations healthy and their profits wealthy - and, with respect to their training, wise as well. Each of these present challenges that are unique to each location, but several key themes emerge across geographies.

In order to break even, agents in densely populated urban areas need to perform an average of 13 transactions per day - while rural agents can get away with a few less (typically between 9-10). Most agents performing between 30-50 transactions a day earn around USD $150 a month, fully recouping their own investment costs in less than a year, but a lot of natural variation means that the top 20-30 percent of agents account for around 80 percent of profits for mobile money providers.

Around 2011, mobile money market watchers began to realize the importance of continual investment to maximize agent agency, signaled by CGAP and GSMA reports defining frameworks for understanding the snags in maintaining effective agent incentives and network structures. This shift also saw a change from speaking about agents as ‘human ATMs’ to actors with substantial responsibilities to the business model success, critically new account registrations - and their subsequent exposure to anti-money laundering (AML) regulations in performing CICO and P2P transactions (not to mention personal safety: 40 percent of agents in a sample surveyed had experienced at least one incident of fraud or theft).

GSMA’s 2018 Distribution 2.0 report captures some of these innovations across four critical stages of mobile money distribution networks: agent on-boarding, training, liquidity management (making sure each agent has enough cash and ‘e-float’ to service customers) and finally agent monitoring. The case studies that have emerged from the agent network pilots cover a wide range of innovative approaches that speak to the disruption enabled by technology in emerging markets.

Digitized on-boarding for both agents and new customers has paved the way for Zoona’s success in Southern Africa, including the employment of alternative data to identify the behavioral characteristics of top performing agents. Predictive analytics are being brought to the float management challenge, as with NovoPay’s integration of advanced GIS systems, and e-learning approaches, leveraging virtualization, gamification, social media and interactive voice response (IVR) technologies, are helping to improve the training and engagement of agents. Shawn Cole, a professor at Harvard Business School who studies decision-making at the base of the pyramid (BOP) expressed optimism in particular for the potential of text-based reminders and ‘rules-of-thumb’ for dispersed networks. Early empirical evidence indicates that useful, just-in-time suggestions sent by text message can measurably change agent behavior at low cost and high scale.

The Last Frontier

So where are the last 1.7 billion unbanked, and how can they be reached? Unfortunately, camouflaged behind the general consensus of the impressive rise of urbanization in the developing world, physical remoteness and extremely low density remain significant obstacles for mobile money’s continued spread. According to Africapolis, a West African / OECD data partnership launched at the end of 2018, the vast majority of African cities contain fewer than 100,000 inhabitants - while 2,000 new cities have appeared in the past 15 years.

Picking locations in which to invest mobile money ‘infrastructure’ - i.e. the people and processes of agent networks - is thus a deeply strategic question inevitably requiring local knowledge, innovation and adaptability. In dense, urban markets, agents may have to compete with five others within a 50 meter radius, demanding high investments in customer service ability and float management to win customer shares. In peri-urban and urban proximate areas, identifying the highest traffic hubs between major cities is key to agent profitability: this means knowing which are the best highway intersections, regional markets or fuel stations in otherwise remote corridors.

For the truly remote, however, mobile money providers would do well to take a cue from those used to operating in these remote conditions: Oolu Solar, a fast-growing PAYG solar provider, has expanded into four countries from its original Senegalese market, and emphasizes there is simply no substitute to investing core competencies in supporting and identifying additional top-performing agents. Targeted investing in financial education thus appears to create a pathway towards the other known benefits associated with mobile money’s contribution to financial inclusion:

"Mobile money has been shown to: enable quicker recovery from economic shocks such as job loss or illness, enable more efficient receipt of monetary transfers from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) after disasters, and lay the foundation for access to formal savings, credit, and insurance opportunities for those who currently lack such access." Inventory Management for Mobile Money Agents in the Developing World, Harvard 2017

Whether the international development community’s financial inclusion goal of 100 percent is achieved by 2020 depends in large part on mobile money operators’ ability to leverage technology and partnerships to scale to the truly remote - as well as secure the financing to do so. Hopefully, this will increase with the growing interest in mobile money cash distribution networks from remittance and fintech players like WorldRemit and TransferWise, as the distance between any two points around the world, financially speaking, continues to shrink. But there is still a ways to go: international transfers are still only available in 51 of the 92 countries where mobile money is available. Even with mobile money, the success story of emerging markets, there is no silver bullet train to the last mile.

Image courtesy WorldRemit Comms

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Regulatory Sandboxes: Worthwhile In Developing Countries?

Culturalization: A Market Entry Deal-Breaker?