PayPal’s Indian Exit and Chinese Entry: Why?

~9 min read

PayPal recently became the first foreign fintech to acquire a coveted domestic operations license in China, the biggest mobile payments market in the world. Around the same time, PayPal also announced it was ceasing domestic operations in India, where the market potential is estimated to reach US$1 trillion. Both China and India’s governments have been influential in shaping their domestic fintech landscape, but differences in regulatory frameworks and strategic vision are shaping how foreign payment providers like PayPal fare in these two countries. China’s two major domestic payment providers, AliPay and WeChat Pay, are proprietary platforms that have ballooned into behemoths — possibly beyond centralized control, authorities there now fear, and creating ulterior motives to allow some outside competition. In India, an increasingly nationalistic democratic government is actuating monetary policy to bring all segments of their population into a formalized financial system for economic stability that at the same time favors Indian banks and domestic payment platforms over foreign fintechs by mandating the utilization of its open-source Unified Payments Interface (UPI) platform to access the wider domestic consumer market.

In this week’s Insight, we peer into how these differences impact endeavors by foreign payment providers like PayPal — and how the markets are subsequently being shaped or influenced to meet authorities’ satisfaction.

Show Them Who’s Boss

From China’s perspective, PayPal was a strategic choice to allow into the domestic market. PayPal is one of the biggest players in the global digital payments world with 377 million users, but it’s also not decked out with all the ecosystem capabilities like China’s fintech giants. However, PayPal recently stated its vision to build out "more capabilities like super apps" and follow the model already laid out and readily adapted in parts of East Asia.

PayPal obtained a domestic operations license by buying a Chinese fintech that already had a license, acquiring 70% of GoPay (a different entity than Indonesia’s GoPay) in 2019. At the end of 2020, PayPal acquired the rest of the company, thereby granting PayPal a full-fledged domestic payment platform.

This historic acquisition of a premium Chinese domestic operations license by a foreign fintech firm opens up an enormous domestic market that relies on digital wallets more than any other payment method. Even if PayPal were to take only a sliver of the Chinese payments market, they would stand to profit in a lucrative market.

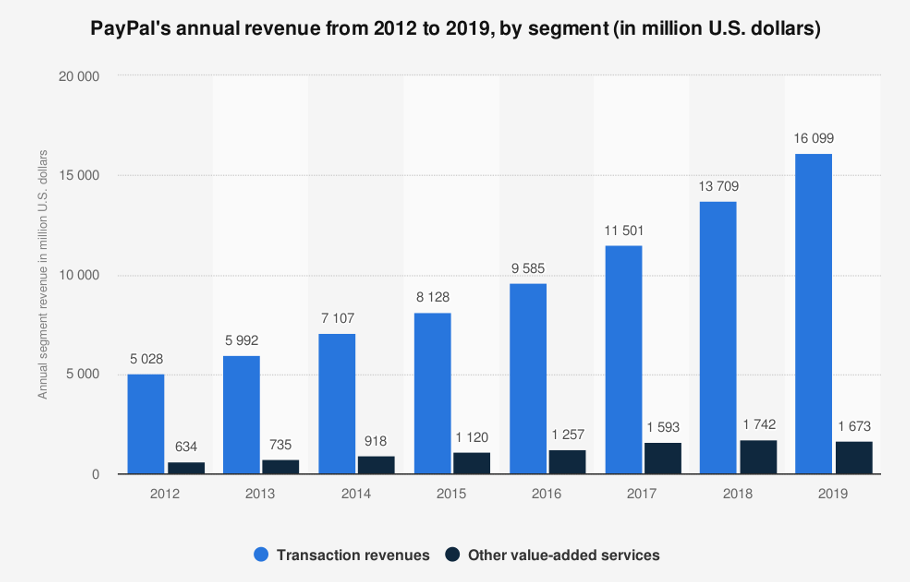

Source: PayPal, 2020

PayPal’s complete acquisition of GoPay wouldn’t have occurred without the tacit approval of the Chinese authorities. Taking place within months of Ant’s halted IPO, the approval was likely a way to curb domestic monopolies that authorities felt they were losing control of. One of the challenges to Ant Group’s recent attempt to IPO was their ambition to function as a bank without complying to regulations regarding capital reserves. Although Jack Ma has recently suggested creating partnerships with state financial institutions as a way forward, his rhetoric in the past often bespoke of a growing independence from regulators that seemingly can no longer be tolerated. If anything, Chinese regulators are using PayPal’s entry as a warning to Ant Group and Tencent: toe the party line, or risk your market supremacy.

“China has two extremely big players, and Jack Ma has been put under some pressure. The Chinese government may be thinking we need another player to have a countervailing force. That might be a reason for allowing PayPal to become a player in the domestic market. The Chinese tech giants will start to penetrate other parts of the world and PayPal can compete with AliPay and WeChat Pay.”

Professor Robert Burgelman - Edmund W. Littlefield Professor of Management, Stanford University

That doesn’t mean Chinese authorities envision PayPal as a real threat to its domestic giants, however. Before PayPal’s entry, China had slowly started to open their mobile payments market to foreign entities. In 2018, China announced it would allow foreign third-party mobile payment platforms to enter the Chinese market, although the government has been slow to grant licenses. Recently, MasterCard was approved to set up a bank card clearing business, and American Express was granted a network clearing license to become the first foreign payment network licensed to clear transactions in renminbi in China. But both companies have partnered with state entities to pave their entry into the domestic markets, and neither have obtained a domestic operations license like PayPal. It’s likely the market entry of PayPal isn’t so much a matter of genuine market liberalization pertaining to foreign companies, but efforts to maintain market equilibrium and control.

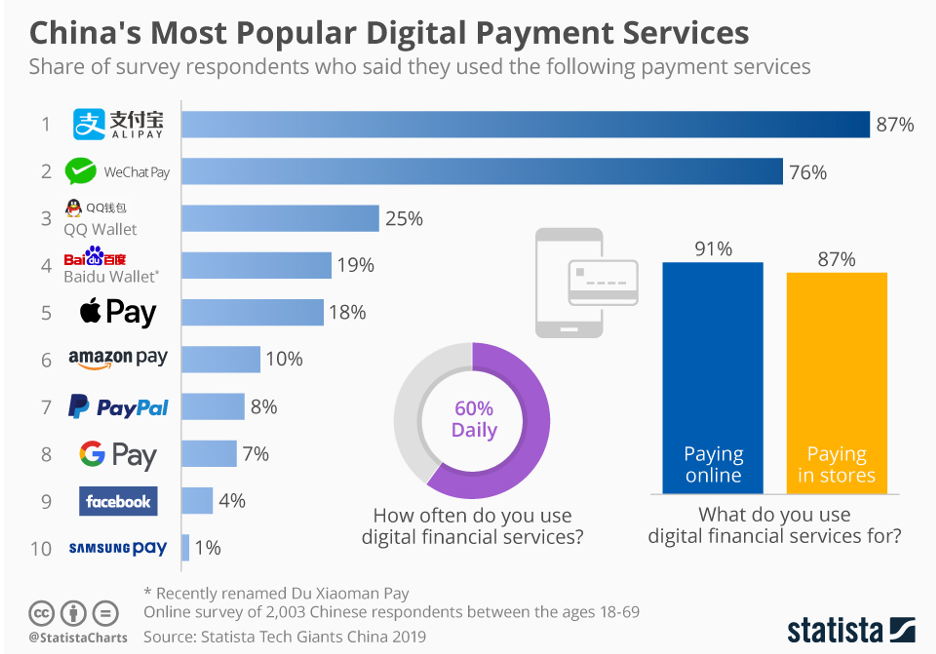

Source: Statista, 2019

“The only reason that PayPal got a license is that they were not a threat. China had no problem kicking Google out of the country because they see it as a threat. Strategically, the acquisition of the domestic operations license is a win for PayPal as a branding and marketing play.”

Alan Tien - former General Manager, PayPal China

Playing By The Rules

At the same time, India’s intricate payments market left little room for PayPal, which observers believe was never able to read India’s domestic market correctly.

“India is a very complicated market for foreign interests. There is strong domestic competition. India has a low-margin, high-volume domestic setting. From a regulatory point of view, the set of issues you have to deal with leads to a complicated, fragmented market. When you have a strong domestic operator like Paytm — players that have been around for a while — their business capabilities are going to be very hard for a foreign entry to replicate. You have to get out in the sticks.”

Professor Ravi Bapna - Associate Dean for Executive Education, University of Minnesota

With its market yet to reach China’s point of maturity and consolidation, India’s government “wants to let their own Indian players get a chance to grow and scale,” said Professor Burgelman. By imposing obstacles for foreign fintech firms, domestic payment providers, including state banks, will have more opportunities to flourish and expand.

A critical issue for PayPal in India was its software didn’t interface with the government’s United Payment Interface (UPI), the open-source banking infrastructure platform used by Indian banks, domestic payment providers, and other foreign entities like Google Pay and Amazon Pay. Though UPI eliminated fees, PayPal retained a transaction fee of 2.5% that drove Indian consumers away. For comparison, Amazon Pay offers up to 5% cash back as an incentive in the Indian market.

In a country home to global call centers, PayPal’s customer service also proved glaringly inadequate compared to domestic competitors; while PayPal customers only had email options for customer service, domestic rivals often allow convenient video calls as customer service options, noted Prantik Ray, a professor at India’s Xavier Institute of Management.

To add to the payment provider’s misery, PayPal faced banking and legal challenges when confronted by India’s UPI-based model, resulting in penalties and business losses. PayPal as a foreign operator is not alone on this front in India, especially after India announced it was capping third-party applications providing payments services via UPI at 30 percent of total transaction volumes, which will limit the expansion of foreign fintech players. It took WhatsApp Pay months of legal wrangling regarding data privacy and localization to transact UPI payments — and now it will only be allowed to extend its payment services to 5% of its 400 million registered users there.

With such regulatory actions tipping the scales in domestic companies’ favor, other foreign payment providers may follow PayPal out the door as regulatory restrictions pile on.

When Cross-Border Success Transcends Domestic Strife

In spite of fraught domestic operations in India and China, PayPal’s strength in cross-border payments may be the life preserver that keeps the fintech afloat in these foreign waters — whether that's becoming the only basis of operations in India, or carrying the weight in China going forward as it begins its foray into the domestic market. Cross-border payments accounted for 19% of PayPal’s payment volume in 2018. The American tech giant already operates in 200 markets and supports more than 25 currencies, offering it a distinct edge on this front.

Having a domestic operations license in China “will bring a halo benefit for their cross-border business,” said Tien, formerly of PayPal. In 2016, cross-border e-commerce in China amounted to US$6.6 trillion, which is only expected to grow as the burgeoning millennial middle class expands their online shopping habits. Asian consumers are one of the biggest purveyors of foreign luxury consumer goods, like designer handbags, buying directly from foreign e-commerce sites — where often Chinese digital payment options aren’t available, but PayPal is. Chinese tourism to foreign countries and overseas education are also avenues for PayPal’s cross-border business to expand. Chinese consumers can easily obtain a Visa credit card at a local bank, even if they can’t use it domestically, though China’s consumers typically prefer digital payments over credit cards.

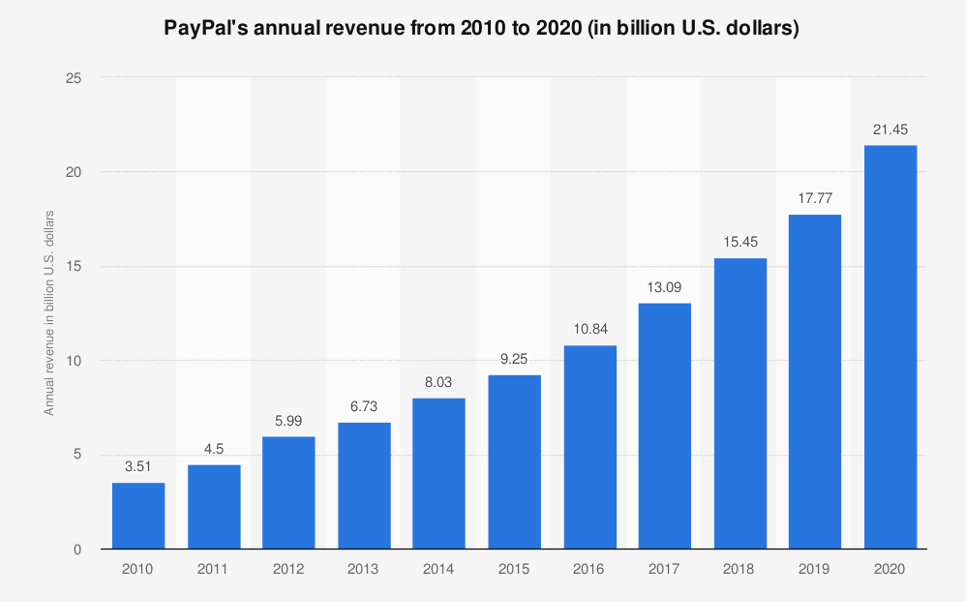

Source: PayPal, 2020

Though PayPal already has a footing in the cross-border payments market, Chinese domestic competitors naturally have their sights on that sector as well. AliPay and WeChat Pay are already accepted in 40 countries. Bill Deng, co-founder of XTransfer, a Shanghai-based payment start-up, stated to Reuters his company’s desire to become “China’s PayPal in cross-border business,” in fact. The question becomes whether these domestic companies can expand outward to compete with the PayPals of the world on an international, cross-border stage — and whether PayPal’s domestic market will sufficiently materialize to justify sustained operations.

“It’s hard to know how PayPal will fare a few years down the line. The first couple of years will require investment into the domestic market, which will be subsidized by the cross-border business. At what point will it not be viable anymore?”

Alan Tien - former General Manager, PayPal China

Involved in India’s cross-border transactions for over a decade, PayPal will continue to operate in that space even as they end their domestic operations. In 2020, PayPal processed US$1.4 billion in international sales for Indian merchants, growing by 22%. Not making the same mistake twice, PayPal recently configured their Xoom platform to interact with the UPI infrastructure so Indian diaspora can send cross-border remittances to their families in India.

“To me, PayPal’s effort in cross-border trade is a wonderful opportunity for the tech giant to tap into the higher end of the marketplace. It’s a strategic landing worth the time and effort as opposed to getting into a dog fight with the established domestic players in India,” added University of Minnesota's Professor Ravi Bapna.

The forthcoming maturation and stabilization of cross-border transactions in Asia means that consumers will only further engage in retail ecommerce, remittance payments, tourism and trade. Connecting middle-class Chinese consumers to global retail markets will increase profits for small and medium businesses with spending power and expedient transactions — and offering a lasting niche in such markets for foreign payment providers like PayPal. One study found that 77% of Chinese tourists spent more money on recent overseas trips using mobile wallets than they had previously spent in previous trips, encouraging Western stores to adopt Chinese digital payment offerings. In such instances, foreign fintech payment platforms themselves can reduce friction resulting from transaction fees, foreign exchange conversions, and the facilitation of international trade — a reversal of PayPal’s fate in the domestic Indian market. By following this path, PayPal can pave the way for Chinese banks to transact with foreign banks through secure channels.

If PayPal scrapes away at a small market share of the Chinese domestic market, it’ll gain profit, PR, and possibly expand its capabilities in a superapp environment, facilitating PayPal’s grand vision in other markets as well. But even if its domestic operations beat the odds and carve out a viable market share, it is likely that governmental pressures sooner or later will make business increasingly difficult, just as India has made PayPal’s domestic operations too challenging to sustain. Ant Group may currently be in the crosshairs of Chinese authorities, but it is still a domestic Chinese unicorn — which PayPal is not and never will be. However, that PayPal hasn’t really lost much in either of these markets — with its cross-border business remaining intact, if not thriving — bodes well for the resilience of international payment providers to domestic protectionism. Cushioning itself through its growing cross-border transaction operations, PayPal has the means to ride the rollercoaster of these vast — if less than foreign-friendly — domestic markets.

Image courtesy of Pinterest

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Can Personality Predict Loan Performance?

Islamic Fintech: An Ethical Financial Inclusion Proposition