Pensions Make Perfect: Roping In The Informal Economy

~6 min read

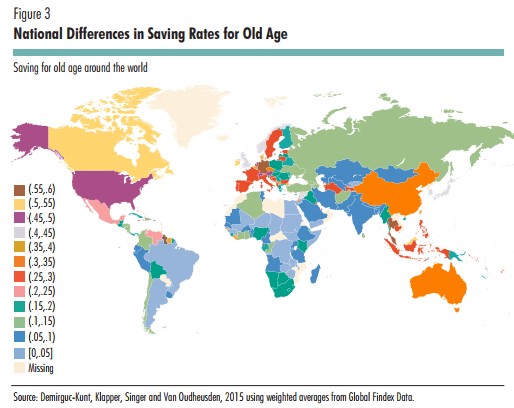

As melodramatic as it may sound, the slow extinction of the joint family, a system historically favored by agricultural communities, and its displacement by nuclear or single-family arrangements common in industrial societies, has forced a reckoning across the developing world. The ‘bareness,’ so to speak, of pension saving schemes in many, if not all, of these markets foreshadows a future of overwhelming old-age poverty, heightened too by gains in life expectancy. According to Findex data, not only does the long-term savings rates in these regions float anywhere between zero to 25 percent (refer to the map below), but pension coverage in emerging economies bottoms out at 5 percent and rarely breaks above 20 percent.

In contrast, many advanced Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, whose labor forces are blessed (or, structured) with large formal contingents, have achieved a pension coverage of 100 percent with a lever in place for auto-enrollment through employers. And, while pension strategies first formulated in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries may not be perfectly translatable, they are a precious resource as state leaders hope to mock-up their own initiatives.

In fact, after weeding through the efforts of years past, the World Bank first introduced a three-tiered model in 1994, designed to better inform and conceptualize any attempt to induce pension coverage at the national-level. That model was then expanded in 2008 to better capture non-contributory, non-financial or informal mechanisms that, too, factor into the health of pension systems. In a succinct overview, the pillars were described as such:

- Zero Pillar – non-contributory social assistance financed by the state, fiscal conditions permitting

- First Pillar – mandatory with contributions linked to earnings and objective of replacing some portion of lifetime pre-retirement income

- Second Pillar - mandatory defined contribution plan with independent investment management

- Third Pillar - voluntary taking many forms (e.g. individual savings; employer sponsored; defined benefit or defined contribution)

- Fourth Pillar - informal support (such as family), other formal social programs (such as health care or housing), and other individual assets (such as home ownership and reverse mortgages)

Much of the progress realized in terms of pension inclusion is the consequence of engaging informal labor on a voluntary basis (third pillar). By slowly - and optimally, organically - corralling informal workers through appropriate incentives and technology, the prospect of a successful, mandatory tax-financed public or occupational pension (first and second pillar) campaign becomes more conceivable. Pension product launches across Kenya, Mexico and South Africa are trialing as first impressions, and populations ‘peripheral’ to the pension are coming into the fold.

Kenya: The ‘M-Pesa-Mbao’ Combination

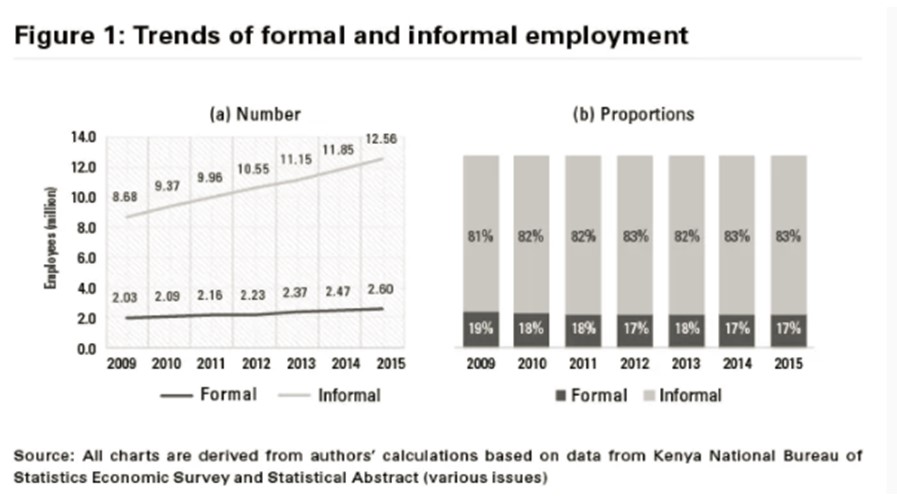

If there were ever ideal conditions to experiment with pension innovation, Kenya decidedly fits the bill. In 2015, a report by the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Africa lamented its comparatively high ratio of informal sector employment (nearly 78 percent!) to other counterparts such as Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania and Uganda. And, since 2009, its labor market composition has only furthered skewed away ‘officiality’ as the growth of the informal economy outpaces that of the formal.

On a less sour note, Kenya remains the uncontested champion of financial inclusion, with access to formal financial services springing from 26 percent in 2006 to 75 percent in 2016. With M-Pesa the primary vehicle behind such strides, it should be of little surprise that any hope of organizing and harnessing the collective power of an informal worker coalition must incorporate it into its operations.

The Jua Kali Association, an umbrella group that unites informal trades across Kenya, has sponsored the Mbao Pension Plan since 2011 in collaboration with the Retirement Benefits Authority (RBA). Mbao is a voluntary defined contribution provident fund, whose name itself hints at the minimum daily quota. A Mbao is a Kenyan colloquial term for KES 20 (or about USD .20). Those registered with the pension plan are expected to set aside an average KES 20 per day, which can be smoothed over by bulk sums to account for seasonality or periodic loss of income. As of 2015, the pension fund was worth KES 100 million between 70,000 members – the largest independent pension plan (IPP) to date active in Kenya. As stipulated by regulation, the Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) shepherds the fund and has invested it in low-risk money market securities and treasury bonds.

And while the low value of the contribution floor clearly accommodates the unpredictable earnings and lifestyle of informal workers, so too do Mbao’s payment options. Mobile phone technology, namely Safaricom’s M-Pesa and Airtel’s Airtel Money, keep even the smallest transfers affordable and convenient, with a KES 0 to 49 mobile money pension installment costing KES 3. Remote, digital pay-ins are as important as product design if informal workers are to actively manage their pensions and the accompanying obligations.

How do I save in Mbao via M-PESA?

- Load money to your mobile phone

- Go to M-Pesa menu

- Choose pay bill

- Enter business No 710 710

- Enter account number - Your ID number

- Enter the amount you want to save

- Enter M-Pesa PIN Number

- Say OK

Mexico: Widening The Net

Comisión Nacional del Sistema de Ahorro para el Retiro (CONSAR), the regulatory body responsible for the oversight of the country’s pension fund administrators (Afores), settled on a multi-pronged approach to encourage voluntary pension saving by informal workers: (i) channel diversification, (ii) reformulation of target demographics and (iii) non-monetary incentives.

Layering upon previous channel diversification steps enacted in 2015 – a move wherein individuals could place lumpsums into existing Afore accounts through common retail outs, Bansefi brick and mortar locations and Telecomm agent banking – CONSAR authorized a smartphone and feature phone-friendly payment platform, Transfer, to facilitate Afore mobile-first deposits in 2016. This platform was then opened up the following year to independent laborers who are residing either in Mexico or abroad in the United States. In addition to these actions, CONSAR is grounded in behavioral science and has dabbled with projection modelling of pension income, available for free on its website for affiliates of the Mexican Social Security Institute and informal workers. It has also tinkered with financial literacy campaigns, and the impact of certain words of phrases on long-term old-age saving patterns.

South Africa: A Group's Pact

Implicit in the story of the Jua Kali Association is the virtue of groups as aggregators – whether that be microfinance institutions, co-operatives or more. These aggregators function as a stand-in for employers in the process of enrollment and contribution batching for the informal sector.

In South Africa, Nobuntu is a ‘community-minded’ self-help product that intends to do just that. Through its capitalization on efficient capital structures, coupled with digital communication and payment tools (currently facilitated by bank EFT and debit order, with mobile money in South Africa nothing short of a flop) offers a simple, low-cost pension that increases in value as a policy-holder ages.

The group element is central to guaranteeing that promise. By pooling funds, financial liabilities are diffused among many, and profits are generated by both returns from a low volatility portfolio and sharing of longevity risk (i.e. "mortality credits") projected through the use of actuarial life tables (South Africa and Kenya are the lone implementers of country-specific mortality tables on the continent). Collective saving, too, more accurately mirrors indigenous savings mechanisms, and reaffirms informal participants’ sense of identity, solidarity and independence. But, voluntary initiatives cannot holistically replace the first or second pillar – if anything, perhaps the third pillar is the perfect pension gateway, tentatively to be absorbed by mandatory schemes:

As there is a degree of compulsion, State-mandated saving is often necessary in order to force people to save for their old age. It is difficult to save for the long term, even with a sophisticated understanding of financial wellness – it is much more difficult when your financial education is limited and you have urgent demands for short-term needs or liquidity. Nobuntu is not looking to replace these mandated savings schemes at all, but rather we are looking to be a more appropriately designed and cost-effective option for these mandated funds to be invested in. Tyron Fouche, Chief Executive Officer of Nobuntu

So, as the third pillar – due to its voluntary nature – is an ideal space for research, development and innovation, first and second pillar schemes should, especially within the context of the informal sector, borrow its advances. So, how have regulators in emerging markets propositioned the pension market, and what more can governments do? More on that to come.

Image courtesy of Rajarshi MITRA

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Voice + A.I. = Frictionless Payments?

Digital Identity: The Private Sector Takes Aim