Regulatory Sandboxes: Worthwhile In Developing Countries?

~6 min read

The predecessor of the regulatory sandbox first appeared in 2012, when the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) inaugurated Project Catalyst as a way to cultivate ‘consumer-friendly’ innovation. A few years later across the pond, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) baked the antecedent concept into an institutional framework which, when fully polished, took form as a regulatory sandbox wherein authorized fintechs were 'allowed to test innovative propositions in the market, with real consumers' while accountable to safeguards. Although the sandbox may have originated in a high-income country, and most quickly resonated with spitting-image markets like Hong Kong and Singapore, its appeal has inspired more than 20 nations worldwide to follow suit, of which 10 are developing.

Momentum does not seem to be slowing either with more initiatives coming out of the woodwork. The Capital Markets Authority (CMA) in Kenya is, at long last, considering prospective fintechs to fill out its awaited sandbox. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), meanwhile, recently released preliminary guidelines to which stakeholders are unabashedly providing feedback (cryptocurrency related ventures are particularly vocal in light of their outright exclusion as the drafted sandbox currently stands). Unlike wealthier regulators, though, sandboxes in developing countries have less latitude to leisurely hone in on productive innovation; resources are much more precious. There has to be an efficacy and exactness, therefore, closer to a truffle-sniffing pig than a retiree with a newfound hobby in metal-detecting.

Setting-Up Shop

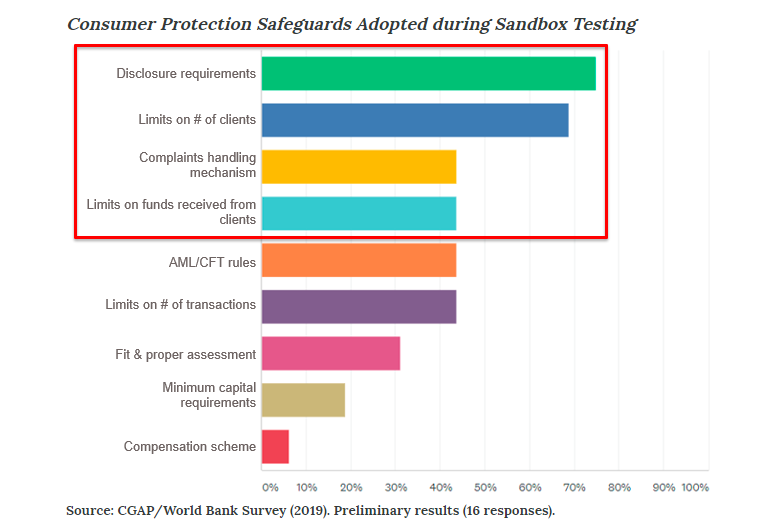

The FCA, as the first implementer, has left a firm impression with many shaping themselves in its mold. Despite variations, most sandboxes adhere to its established, simple format in carving out exceptions for regulatory non-compliant, yet operational firms: application, selection, testing and exit. Eligibility, instead, is less standardized and more scattered. Some sandboxes favor incumbents, others start-ups. How segregated sandbox participants remain from the general public (usually in the form of customer caps), or whether or not a compensation fund is a precondition in the event of a breakdown, are idiosyncratic to each sandbox.

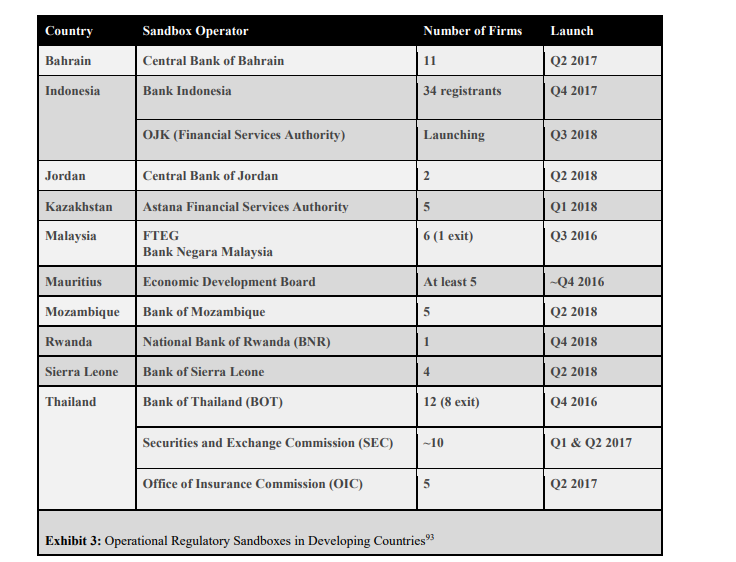

So, with some reflectors illuminating and demarcating a crude path forward, a handful of developing countries have volunteered themselves as guinea-pigs in this regulatory thought experiment. According to the Digital Financial Services Observatory, as of October 2018 there were 10 operational sandboxes that fit such gating criteria: Bahrain, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Thailand. While the list has its own points of potential dispute - from controversy around Bahrain's classification to the intentional omission of the Philippines (the Philippines prefers a 'test-and-learn' equivalent, where, through the issuance of letters of no objection or waivers, fintechs are not beholden to specific regulation) - it captures sandbox happenings at the global level.

Source: The State of Regulatory Sandboxes in Developing Countries

Source: The State of Regulatory Sandboxes in Developing Countries

Consistent in sandboxes' adaptation across continents is the onus placed on financial innovators to articulate the regulatory uncertainties or incompatibilities implicit in its operations, whether that be in relation to a business model or technology. Much more narrow to the 10 sandboxes, however, appears to be priorities. Bahrain, Jordan, Malaysia, Mozambique and Sierra Leone have all interwoven financial inclusion language into overarching objectives; in fact, the sandboxes of Malaysia and Sierra Leone are dedicated to solutions that advance finance inclusion (a new trend dubbed a thematic sandbox).

Thailand has also internalized the thematic sandbox approach, but deconstructed it on its own terms. Instead of one all-encompassing sandbox, different regulatory bodies - which includes the Bank of Thailand, Thailand Securities and Exchange Commission and the Office of Insurance Commission - are all custodians over independent sandboxes most relevant to their respective jurisdictions. Indonesia, too, has embraced a fractional sandbox order, with responsibilities split between Bank Indonesia and the Financial Services Authority. In the case of Rwanda, while the sandbox there may skirt explicit framing, the only fintech so far to be inducted is the mobile wallet provider Riha Payment System who has overtly described its target customer segment as the unbanked.

Busking For... Pennies?

With the lofty intention of impact shadowing regulatory sandboxes in developing countries, the stickier issue becomes quantifying it. There is currently scant evidence across all regulatory sandboxes as to what the demonstrable impact actually is, so the foundations that could inform benchmarking are still likely years away. A report circulated by the FCA after its first cohort is perhaps the best effort yet in nailing down actionable intelligence, which focused on firm-level performance:

- 75 percent of firms in the first cohort successfully completed testing

- Around 90 percent of firms that completed testing in the first cohort continued toward a wider market launch

- The majority of firms transitioned from a restricted authorization to a full authorization upon completion of their testing

From the FCA's perspective, it is clear that success is conflated with the 'graduation' of participants from its sandbox with regulatory approval. That metric might be sensible for a sandbox that has, since 2015, invited 118 fintechs to partake in one of its five cohorts. But for sandboxes in developing countries, only Bahrain, Indonesia and Thailand have bucked the 'low-enrollment' trend (see Exhibit 3 above), and that is with the extraordinarily low baseline of just 10 fintechs enrolled since a sandbox's inception. If a regulatory sandbox exists just to exit one or two previously non-compliant fintechs, that seems like grounds for accusations of bureaucratic waste.

Instead, there might be a softer power to regulatory sandboxes. Self-reported data by regulators reveals just how persuadable policy-makers can be when afforded the opportunity to toy with and understand innovation first-hand. Half of all financial sector regulatory authority respondents - 28 total - surveyed by CGAP and the World Bank had implemented regulatory changes in reaction to findings brought to light by sandbox testing: technologies of escalating interest cover areas like crypto-assets, initial coin offerings (ICOs), crowdfunding, cybersecurity, cloud computing, e-money and biometric authentication.

The better indicator to evaluate sandboxes in developing countries, then, might be their contributions in tweaking regulation to better enable financial inclusion. Malaysia is one such illustration of what is at stake and the possible wider repercussions. WorldRemit, a remittance service provider, relies on electronic know-your-customer (e-KYC) verification, with supporting identity documents submitted via mobile. When WorldRemit first entered Malaysia's sandbox back in May of 2017, e-KYC was incompatible with the regulation at the time. Under the scrutiny of the sandbox, WorldRemit localized its product which was eventually fully authorized to operate in the Malaysian market. The regulator subsequently drew up and standardized e-KYC guidelines to encourage competition from other innovators - to the benefit of retail remittance customers.

Detractors At The Door

Still, there are those that believe that sandboxes are, for all intensive purposes, overkill and that there are easier, cleaner fixes at regulators' disposal. The Chief Executive Officer at BitPesa, for example, has thrown her weight behind reciprocal licensing programs. In her opinion, sandboxes are just short of a kiss of death for partnership building as incumbents are wary of anything relegated to the regulatory gray zone, thereby inhibiting any meaningful scale (ironically, though, that is by design as evidenced by sandboxes' customer caps). Reciprocal licensing programs, in contrast, catalyze scale without all the fuss (not to mention, resources) that comes with assembling a new sandbox.

"Critical to enabling partnerships is regulation, and currently the fragmented regulation makes strategic partnerships hard to establish. In order to more quickly facilitate the success of fintechs, emerging market governments should start trial reciprocal licensing programs from other jurisdictions as well as be willing to extend existing regulations to new technologies." Elizabeth Rossiello, Chief Executive Officer at BitPesa

Sandboxes, however, need not necessarily cause siloed progress in regard to innovation. If coordination for cross-border private and public sandboxes can be struck on an international level - with the fruition of the ASEAN Financial Innovation Network (AFIN) or the Global Financial Innovation Network (GFIN) - surely, so too can it be struck across regulatory agencies domestically? This line of questioning could be premature though, given that developing countries are still waiting on definitive proof that sandboxes drive valuable regulatory change. The best bet might be a hedged bet with small, thematic sandboxes treated as the putty filling in regulatory holes - similar to Vietnam's tentative telco-specific sandbox to pilot mobile money.

Image courtesy Jared Tarbell

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Paytm: Are One Billion Credit Cards Coming To Asia?

The Last Mile: Mobile Money Agents