Senegal: Turtle Or Hare Of West Africa DFC?

~8 min read

Senegal has long occupied a special place in Francophone West Africa. Home to the historical capital of the French colonial empire, Senegal is distinguished by a uniquely stable democracy, and is one of the only countries in West Africa never to have experienced a military coup. It’s omnipresent French influence is counterbalanced by a decidedly unique Muslim character: with 94 percent of it’s population described as Sufi (following a idiosyncratic system of "Muslim brotherhoods" that has little in common with either the Persian mysticism or Egyptian political movements typically associated with these terms), it was the first African country to institutionalize Islamic Finance.

Its position as a DFC hotspot is also exceptional, birthplace to regional champions in P2P and cross-border transfer like Wari and Touch. Indeed, Senegal’s attractiveness factors as a DFC ecosystem are many, including a strong public administration committed to digitalization, ambitious plans for urban renewal through a smart-city program, renowned universities and a significant and wealthy global diaspora - all contributing to one of the most diverse and dynamic mobile money ecosystems on the continent. At the same time, it suffers from familiar challenges endemic to the region, from expensive and unreliable data access to notoriously slow-moving banks, generating in equal parts excitement at the signs of growth and innovation and exasperation at the persistence of traditional modes of transacting. In such a DFC ecosystem, rife with both opportunity and scarcity, which strategy is better positioned for success, the persistence of the turtle or the alacrity of the hare?

Mobile Money Snapshot

As one of the fastest growing economies in Sub Saharan Africa with a 6 percent average annual GDP growth since 2015 and 102 precent phone ownership, Senegal’s economy has remained consistently a stable grower. Yet mobile money usage remains limited overall: only ten percent of Senegal payment flows are digitized in terms of value and six percent by volume. It is dominated by over the counter P2P transfers, with agents earning some of the highest commissions of any African country. A particularity of the agent dynamic is that Senegalese mobile money agents are disproportionately non-exclusive and non-dedicated - meaning the agent network is largely composed of informal FMCG shop owners who offer multiple mobile money services.

The importance of this dynamic, in part caused by low digital literacy rates and consequent limited trust of virtual money, has far-reaching impacts on growth strategies for businesses banking on the convenience of digital payments to streamline their operations. Wari, an early success story in mobile based money transfer in Senegal and West Africa, gained rapid market dominance in the 2000s by recognizing the power agents have in influencing mobile money uptake among users and by offering them higher commission rates than competitors. While passing on some of these costs to customers has contributed to the perception that mobile money is yet too expensive to be frictionless, it also catalyzed a market-shaking development in prompting Sonatel - the Senegalese version of French telecom giant Orange - to go it alone and build out their own network of dedicated agents across the country.

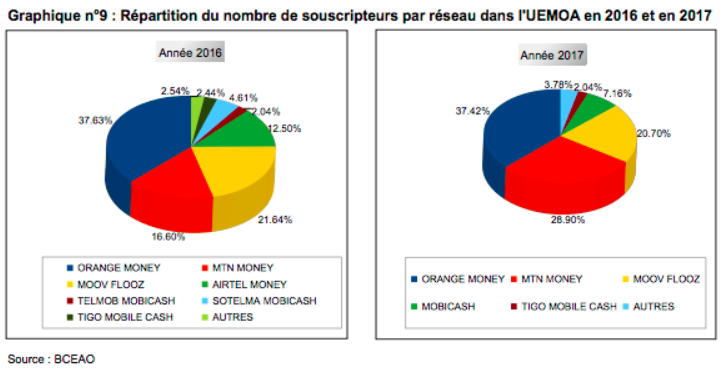

The rise of Orange is perhaps the biggest story of Senegal’s mobile money playground of the past few years. The reliability of its technology, ubiquity of cash-points and aggressive marketing have seen it emerge as the leader in mobile money transfer services not only in Senegal, but across many of the West African Monetary Union countries it operates in. Since gaining its e-money license in 2016 (allowing it to interface directly with local banks), Orange Money claims to have registered over 40 million accounts in at least seven African countries (French) at the end of 2018, 13 million of which transact at least once a month. Though its dedicated agent network represent less than 5 percent of its 160,000 cash points continent-wide, its strategy leans heavily on its European advantages - partnerships with local affiliates of Total, BNP Paribas, and supermarkets like Hypermarché grant it unrivaled network effects.

Orange’s mobile wallet and e-money solution covers most of the basics of DFC use-cases - offering OTC transactions from its cash points, wallet-to-wallet P2P transfers, airtime top-up, bill pay for satellite TV, water, and electricity (including pre-paid, post-paid and PayGo solar), regional transfers, P2B payments to a number of partners, and even wallet-bank transfers with three of the largest banks in Senegal. Two other MNOs offer mobile money (Tigo Cash and Expresso Money), but pending corporate restructuring shakeouts, neither pose a serious threat. Wari, and to an even greater extent its smaller OTC competitor Joni Joni, aspirationally offer some of the same services as Orange, but have suffered reputationally from frequent technical outages, while bank-led e-money initiatives like Bank of Dakar’s Cash Cash and Société General’s YUP try their hand at mobile banking for an existing but marginal clientele.

The explosive growth of Orange Money has not been without backlash. Charges of monopolistic behavior are a frequent refrain, as when Senegalese regulators ruled that Orange the telecom company cannot offer airtime discounts for bills paid through Orange Money. For many, however, the writing is already on the wall. The behemoth, relatively late to the starting line, is steadily eating up market share in Senegal - with no heavyweights like MTN to contest its fiefdom as in neighboring Côte d’Ivoire.

But, No M-Pesa

A realistic appraisal of digital finance in Senegal should draw only careful comparisons to its East African analogs. The ubiquity and functionality of Kenya’s M-Pesa, for example, is assuredly in a superior category of mobile money uptake than in Senegal. Yet for all the increased convenience of developing DFC use-cases on top of ubiquitous mobile money use, Senegal offers to the discerning investor or market expansion opportunist an impressively dense ecosystem of players.

ShopMeAway, an e-commerce provider qua logistics aggregator that competes indirectly with the local branch of Jumia, encapsulates the uneven integration of Senegal’s emerging middle class into global markets. Racine Sarr, its founder, returned to Senegal after professional experiences in France’s traditional formal banking system, and ruminates on some of the cultural similarities and differences to doing business in the two countries. Unlike France’s rigid conception of how business is done, “here [in Senegal], a lot of things are still to be done and we (the private sector) are not necessarily waiting for the State to provide solutions.” This attitude allowed him to create in his own words “the Groupon of logistics”: Senegalese purchasers order items on global marketplaces like Amazon to in-country aggregation points, which are then shipped in bulk to ShopMeAway’s Dakar depots. Selling a kilogram of air freight at a pooled and discounted price allows him to charge 4x less than DHL, without having to worry about maintaining stock.

He notes the tangible impacts that the start-up scene in Dakar has experienced since it began to pick up steam as a hub for incubators, accelerators, co-working spaces and maker labs. An injection of young, tech-savvy repatriates like himself into governmental positions has also had an impact in terms of the implementation and execution of support mechanisms to support digital technologies, including government-backed loan-to-equity schemes and other start-up fast-track initiatives (French) that have seen success in other African countries.

Though political mismanagement is always a concern (and has reared again at the highest levels with renewed interest in fossil fuel exploration), there is little doubt that the government can and has delivered on many of its promises: infrastructure reforms outlined in Senegal’s 2015 Plan Senegal Émergant have nearly halved travel times from Dakar to many secondary cities relative to only a few years ago, a point of pride amongst Senegalese of all orientations. If success in deploying ‘hard’ infrastructure is any indication, then the DFC ecosystem should indeed bank on some if not many of the 28 reforms and 69 projects promised in Stratégie Sénégal Numérique 2025 (with over $2b USD in associated funds earmarked (French)) to see the light of day.

Plenty of room for competition remains in Dakar’s burgeoning start-up scene - aside from Jumia, e-commerce niches are being carved by local players like OuiCarry, Paps, and Sooretul. Many startups involving physical products confront the spatial challenge of informal construction and poor street signage - particularly sensitive for products that spoil, like Club Kossam’s (the key to efficient delivery of fresh milk from Senegalese herds directly to Dakarois consumers: clustering each neighborhood by a specific day for delivery). For most startups, cash on delivery will likely remain king until the convenience of cashless outstrips the mobile money markup, both in percentage terms and in the time it takes to go to an actual, physical person, the way most mobile money transactions are still performed here.

While few Senegalese startups have reached scale so far, some of the most successful are those that have embraced the challenges of a fragmented mobile money ecosystem. Oolu Solar, after having scaled to five countries with its off-grid energy products, pains itself to accept whatever form of e-cash its customers can access. While the vast majority of its users pay with Wari or Orange Money, the running tally of providers in Senegal approaches a dozen, hinting that there is space for multiple mobile money operators to carve geographic and use-case niches beyond Orange’s omnipresent shadow in the capital - a fact not lost by nimble fintechs like Wave and Wizall.

In fact, Orange’s recognition that it cannot do everything has led it to take an explicit partnership approach through its Digital Ventures arm and incubation efforts. For many startups building a space for themselves around or within digital finance - in particular ‘next layer’ DFC use-cases like credit, insurance, mHealth, mAg, logistics, etc - there appears to be an open invitation to work not only around but with the big guys.

Fast, Slow Or Both?

At the end of the day, Senegalese DFC fundamentals are in theory great, in reality difficult, and in practice improving. While investor interest may wax and wane, a strong local economy and indelible ties to Europe, the US and regional neighbors ensures a pace of progress that could be described as plodding - or as persistent. Trends to watch include Orange’s success in moving the mobile money market by consistently delivering a quality product that delivers true P2P functionality (could its e-wallet-to-ATM card offering solve the intermediary problem?), increased government digitization of financial transfers beyond its inter-departmental successes and the promises of regional integration finally delivering results.

The entrance of global heavy-weights, of course, always promises a power-shift; Alibaba, for example, has tipped its interest in African markets by inviting some 50 African DFC companies to visit its headquarters, amongst which was ShopMeAway. Let us not forget that black swan events are often those that matter most.

The lag between action and impact can be long, however, and much otherwise quality analysis of Senegalese DFC dynamics is hampered by a persistent language barrier as well as over-reliance on data that rarely reflects up-to-date market dynamics. To truly understand the lay of the land, there simply is no substitute for a conversation - ideally over a cup of café Touba. As one observes the streets in Dakar, taking a pulse of the frenetic bustle of bright cabs and buses, highway horse-drawn carts, digital billboards overlooking flocks of sheep destined for Eid, it is perhaps the duck that best captures the successful DFC players of Dakar. Those that seem to rise above the rest do not perturb easily, and swerve unerringly forward, like a turtle. Beneath the surface, however, the legs are all hare.

Like what you’ve read? Mondato will be issuing a next-layer Insight report diving deeper into trends, players, and opportunities in the Senegalese DFC landscape in the next month. Email us at info@mondato.com if you’re interested in learning more.

Image courtesy of David Harmantas

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Mojaloop: Taking Stock

Sex Work: Safety In Digital?