Where Refugee Fintech Falls Short

~6 min read

Efforts to provide financial solutions to displaced populations have seen some progress, particularly in stable contexts where business and personal financial interests are protected by governments and civic institutions and personal identities are more entrenched. But in the contexts where refugees struggle with instability, little documentation, a tenuous status or few financial links — i.e. the classic symptoms of being a refugee — those strides can vanish. As politics sometimes place insurmountable complications for even well-designed solutions, expanding financial inclusion to displaced individuals in difficult locales requires a shift in approach that integrates both refugee and solution within a wider market alike.

Many Origins, More Destinations

Beyond the shared experiences of forcible displacement and perhaps downward mobility, refugees are far from a monolith, differing across gender, age, economic and professional backgrounds, among other demographic markers. Economic status diverges further considering their given status or length of stay.

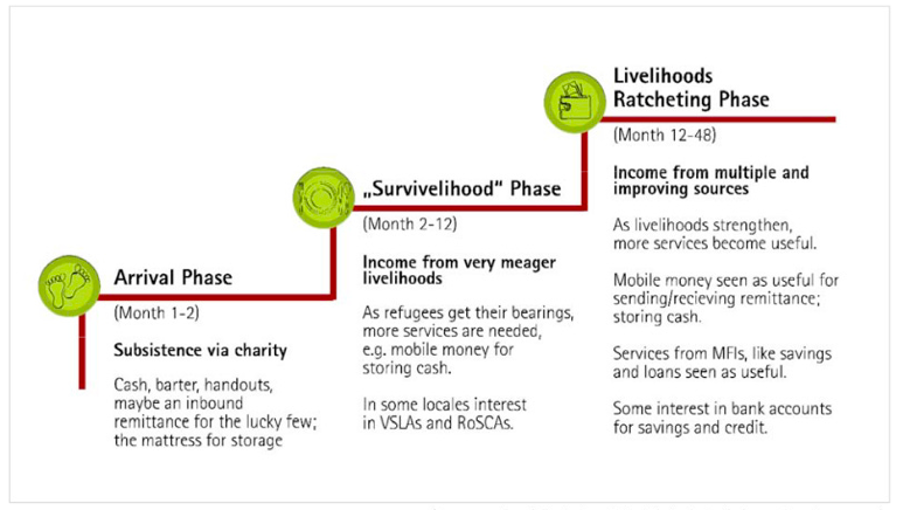

Source: Tufts Journeys Project

The heterogeneity of refugees carries over to their financial services needs, which makes achieving scale for solutions difficult. Some refugees in Kenya’s Kakuma settlement camp, for instance, are self-sufficient with thriving businesses selling to the other settlement camp members. Within the same camp, however, are poverty-stricken families, making up 68% of the population in the camp. These two groups' needs differ, with the latter reliant on cash transfers while the former is more likely to take up more sophisticated services like loan products and insurance. Such divisions within the refugee groups, as well as ethnic divides, reduce their volumes.

Private sector players have consequently been slow to serve these groups, erring on the side of caution. Rwanda’s refugee population is served by a handful of financial service providers, including only one bank, Equity Bank, and a few fintech startups, like Leaf Global, which are the only firms that accept refugee IDs to create accounts.

In general, a lack of financial options persists in spite of the many refugees who have graduated from relying solely on cash transfer programs, numbering about 54% of the refugee population. Yet this untapped market is still small and fragmented. Rwanda’s population of refugees, at about 144,000, is a small market size, especially when divided further along the various demographic and financial situations.

To serve them and achieve growth, a shift towards incorporating refugees among larger, more similar populations becomes necessary. The issues often riddling refugees’ access to financial solutions — lack of documentation, ID, a stable address, savings or a financial history — often mirror those at the bottom of the pyramid, after all. There are a few examples of initiatives with some modest success. Rwanda’s SAVE, a digital platform for savings groups, targets refugees and rural communities. Just a year after it was piloted, SAVE platform had over 4,000 users in 232 groups. In the global south, Leaf Global Fintech, which provides digital wallets for safe financial transactions and storage, began with an aim to help displaced people as they crossed borders. Four years after its inception, it’s expanded to focus on migrants as well across its countries of operation, including Rwanda, Kenya and Uganda.

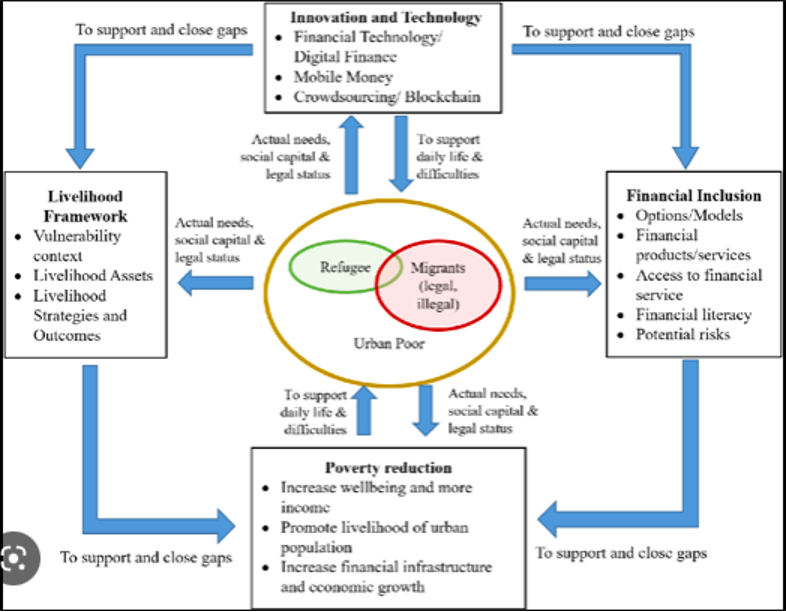

Source: Semantic Scholar

Solutions focused solely on refugees run the risk of only excluding further these populations from key financial products. Refugees in Kenya cannot directly access regular M-Pesa wallets. Closed loop or locked wallet accounts designed for refugees enable the World Food Program (WFP) to distribute cash equivalents redeemable for food items at select stores within settlement camps — a tech-enabled dependency that simultaneously locks them out of access to payment, remittances and money storage of money in the epicenter of East Africa’s fintech revolution.

Yet solutions that are exclusive to refugees — or rather, those that keep them financially excluded — are inevitable results of broader systemic issues.

Are The Gates Open?

To open a bank account or mobile money wallet in most countries, a formal ID is required, and refugees — often stateless and with little to no documentation at all — can be quite constrained by this alone. A given country’s policy seals the fate for many refugees in need of financial access. In Mauritania, a country with over 76,000 refugees and asylum seekers, a refugee ID provided by UNHCR is not recognized by banks — dooming most to exclusion. Rwanda offers an in-between model, with particular banks and mobile network operators permitted to issue accounts to UNHCR ID holding refugees, such as Equity Bank and Leaf Global Fintech.

Properly integrating refugees within a host country’s financial system invites often thorny political issues; inclusive policies may arouse accusations of supporting foreigners at the expense of a country’s own citizens, and AML/ CFT issues can be hard to sort out — perceptually or in fact — when hosting refugees from war-torn countries with little documentation.

Organizations like UNHCR and CALP Network are hard at work trying to bring about interventions that facilitate greater financial inclusion, but the journey is long and slow, and the results are mixed. UNHCR advocacy efforts enabled Zambia’s Central Bank to allow the use of refugee IDs to access mobile money services. Uganda also now enables refugees with valid IDs to acquire SIM cards. But in Kenya, refugee IDs cannot be used to acquire SIM cards, and refugees are unable to freely move outside of settlement camps without permits.

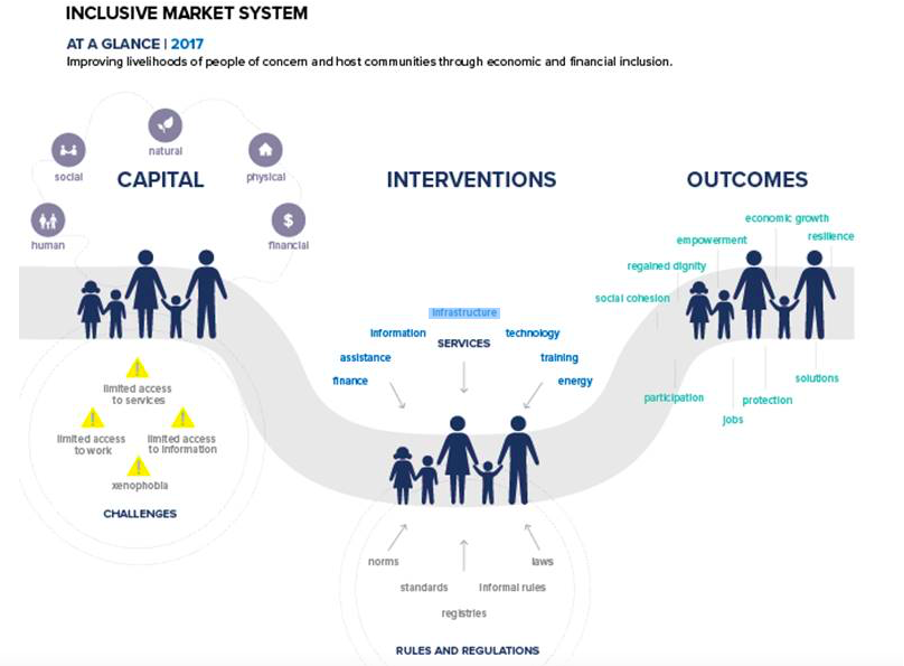

Source: AFI Global

With policy roadblocks often keeping refugees away from formal financial solutions, it is no wonder that informal hawala money transfer systems thrive within asylum-seeking corridors. Certainly, hawala has its enduring uses; humanitarians still use these systems to send out large amounts of cash, as large as $100,000, to areas that are hard to reach, such as Somalia and Afghanistan, according to Kimberly Wilson, a researcher whose work has focused on the financial journeys of refugees.

“[Fintechs] know they are competing with the underground solutions and they don’t have a competitive solution. They lack familiarity [among the refugee populations], and... they want to go to something they understand and trust. Then you add the ID problem as well as the KYC rules. These problems need to be solved if people want to see more formal solutions.”

Kimberley Wilson, Senior Lecturer, The Fletcher School at Tufts University

While the Hawala systems work and are quite reliable, they are often illegal in many countries and have been linked to money laundering and funding of terrorist activities. But it can endure traversing even the most challenging regions, a dexterity of informal methods that tech-based solutions can’t achieve when refugees’ financial access is rarely permitting, and paternalistic at best.

“The technological and the technocratic solutions are pretty straightforward. It just comes down to the politics of the country.”

Rory Crew, Technical Advisor, Data and Digitalisation, CALP Network

Crew gives the example of a blockchain technology provider in Latin America who considered the technology a potentially great way to move money for refugees between countries. But a bank account or mobile money wallet connection is needed to facilitate the blockchain capabilities, which inherently limits potential scale in a region where mobile money uptake is still quite low and bank account ownership among refugees is limited due to a lack of identification documents.

Workarounds can be reached; Leaf Global Fintech for example, has managed to plug in their blockchain-based solution to the vibrant mobile money ecosystem of East Africa. A Leaf mobile wallet user can cash out using any mobile number from its countries of operation (Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda).Yet invariably, few tech solutions truly take off because local policy makes it near impossible for the refugee and entrepreneur alike.

Confronting this murky regulatory environment, financial service providers serving refugees must take a bird’s eye view of the market. This requires diversifying approaches to not only serving low-income refugees with cash transfer programs, or higher income refugees with microinsurance products, or small business owners among refugees with credit products. This integration of both product and refugee within the fabric of a host country’s financial system is critical in engendering both the needed inclusion and business model success that has proven elusive so far. Political barriers notwithstanding, the digital financial service providers best poised to serve these groups, ultimately, are not the most disruptive ones, but those that embrace an inclusive, open tent approach.

Image courtesy of Levi Meir Clancy

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Israel: Can Sentiment Alter A Tech Sector’s Trajectory?

Are Colleges Failing At Blockchain?