Will Vaccine Passports Exclude or Enable?

~10 min read

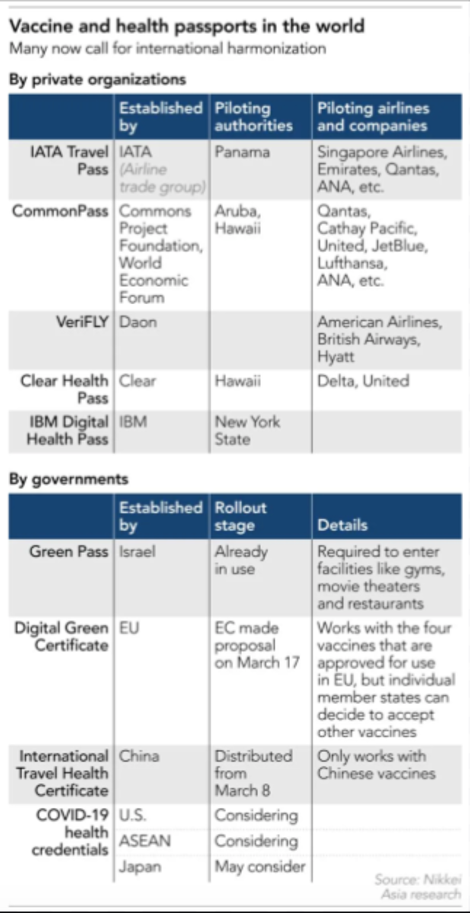

A vaccination clinic in the working class neighborhood of Neve Sha’anan in south Tel Aviv is not like most others in Israel, the first country to vaccinate the vast majority of its adults. The foreign nationals getting vaccinated there — nearly all of whom are asylum seekers and foreign workers — come without an Israeli HMO provider or Israeli ID number. Along with other factors, Israel’s rapid vaccination drive was aided by its sprawling national health care system and universal national ID number database, elements of which are also critical to their COVID testing and immunity certification regimes. Israel’s “Green Pass” is the first and so far, only digital “vaccine passport” — or what experts prefer to call COVID Vaccination Certificates (CVCs) — implemented on a nationwide scale to facilitate the opening of bars, restaurants and large public spaces and events with such credentials, accessible through the government’s Ramzor app. However, without an Israeli ID number, a person waiting in line to get vaccinated at the clinic in Neve Sha’anan has been unable receive the Green Pass credentials. Even for those without an Israeli ID number who did get vaccinated through their Israeli HMO provider, they were unable to receive a Green Pass, either.

In February, Israel’s “Green Pass” regime began in earnest with the express purpose of helping to facilitate the return of normal commerce and to compel vaccine skeptics to fall in line, with the Health Minister declaring that “whoever does not get vaccinated will be left behind.” While Israel — and pertaining to foreign workers and asylum seekers, the Tel Aviv municipality — took efforts to vaccinate foreign nationals and Palestinian workers, no formal exception protocols were devised in enabling the Green Pass app for such populations.

According to the Green Pass regime, they’ve technically been left behind.

Source: Israeli Ministry of Health

Heavily employed in the kitchens of restaurants and hotels, among other service industries, the asylum seeker community saw unemployment hit higher than 70% at the peak of the pandemic. Although data is lacking, many asylum seekers and foreign workers — communities with higher levels of vaccine hesitation — anecdotally describe the threat of losing their jobs as a compelling factor in getting vaccinated. But after leaving the free clinic in south Tel Aviv fully vaccinated, they receive nothing but a text message a week later.

Especially for those who have an Israeli HMO provider and were vaccinated through them, most foreign workers and asylum seekers do obtain some form of credentials — typically a vaccination certificate — thereafter, but it is often an opaque, uncertain process with unforgiving linguistic hurdles, according to local asylum seekers and Dr. Zoe Gutzeit, director of the migrant and refugee department at Physicians for Human Rights in Israel. It’s a hazy situation so rife with informal bureaucratic wrangling — an experience all too common for such groups in Israel without status — that even NGOs focused on the issue are still unsure of its exact enormity or breadth, with conflicting reports from these communities.

This begs the question of the world’s fastest vaccination drive and first “Green Pass” regime: are vaccine passports destined to replicate the exclusionary gaps of foundational ID systems? In terms of both design and technology — no, not necessarily.

Whether a sign of vaccine passport regimes to come or a characteristic of Israeli society, Israel’s Green Pass reality has veered somewhat from the prescribed regime, with Israelis describing inconsistent enforcement at establishments depending on their business, location and management. Although access to the bars and restaurants they often work in is legally tenuous without Green Pass access, foreign workers and asylum seekers have largely been able to keep their jobs with some form of credential or evidence of vaccination, even the lone SMS message received —a kind of lower level of identity assurance — or with employers not demanding proof altogether. This legal gray area does keep the door open for vocational exclusion, with Israel’s Physicians for Human Rights receiving calls from foreign workers and asylum seekers facing such issues (instances included the same medical facilities and nursing homes that foreign workers were vaccinated at). But otherwise, informal means of accepting alternative credentials or foregoing such requirements — in line with Israeli culture — essentially perform the exception protocols that the formal system has so far failed to implement itself.

“When you mandate a foundational ID for a vaccination program like in Israel, then you have to have exception management, or exception handling protocols, for those that don’t have it. The centralization of the database can handle exceptions if you build those exceptions.”

Anit Mukherjee, Policy Fellow, Center of Global Development

Although exception protocols were created for the vaccination program itself, it wasn’t done in synchronization with the corresponding certification regimes until very recently when some — though not all — non-ID holders reported being finally able to receive Green Pass credentials using their passport number (if they had one). Mukherjee related Israel’s issue to the situation in India, where in spite of the country’s robust Aadhaar identification system, multiple alternative forms of identification would be allowed for its digital vaccination credential management system, DIVOC, under development. Standardization breeds efficiency in identity authentication schemes, but without flexibility, it perpetuates exclusion outside the norm. In this sense, when designing vaccination and subsequent certification regimes— both domestically and on the international scale — standardization is the goal, but there must be flexibility geared towards universal inclusion.

With vaccine credential regimes under development elsewhere, not only can this be better achieved through more careful design, but through improved technology.

The Technological Means to Achieve Inclusive Dreams

As countries like the U.K. and China roll out their own initial vaccine passport regimes, organizations like the World Health Organization

and the UK’s Royal Society have released interim guidelines on what digital vaccine credential regimes should look like. The Royal Society’s guidelines, for instance, advocate for credentials which meet benchmarks for immunity, accommodate differences between vaccines and changes in variants, establish international standardization with defined use, ensure interoperability, secure personal data, and make such credentials affordable, legal, non-discriminatory — and based on verifiable credentials.

It will be difficult to align vaccination regimes of countries with contrasting characteristics — how do you make interoperable the certification regimes between countries that do and don’t have national ID systems? How do you reconcile an all-digital certification effort from countries like Israel and all-paper regimes from countries like Germany? How do you incorporate sources of testing and vaccination from various sectors (labs, health ministries, health insurance providers)?

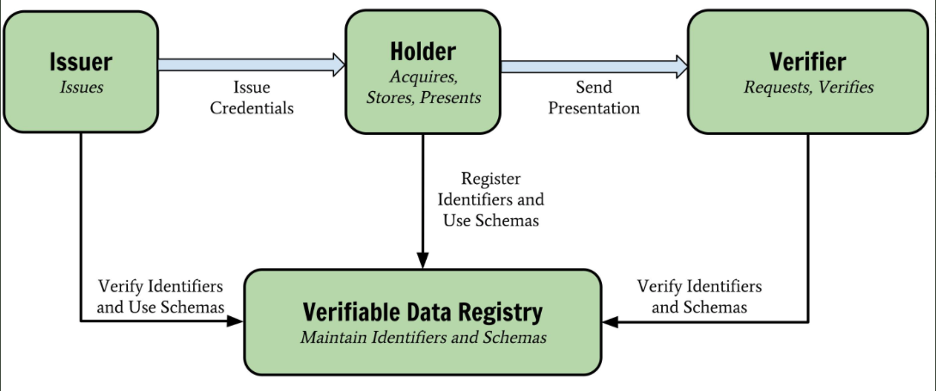

Verifiable credentials have emerged as the proposed solution. Verifiable credentials rely on blockchain technology and the specific W3C protocol developed over the past several years, but it had yet to find a proper use case at scale before now. As a distributed ledger, verifiable credentials will in theory allow anyone within or outside foundational identity schemes to be properly verified by authorities wherever they go. It is also vastly superior incorporating the differing sources certifying vaccination, proof of immunity and up-to-date testing that in actuality will make up prospective COVID health credential schemes. At the same time, it ensures far more data security than centralized servers ever could. Estimating such adoption for COVID credential schemes will advance verifiable credentials technology by “three to five years,” Andrew Bud, CEO of iProov — a biometrics company which is developing along with cybersecurity company Mvine a digital COVID status certification regime in the UK — views the possible adoption of verifiable credentials on a global scale as signifying a massive technological step forward.

“The first deployment of open, standard, verifiable credential technology – that’s really a big thing that transcends COVID. Verifiable credentials are a much more flexible, powerful, useful architecture than digital identity. A digital identity is essentially a dossier that somebody builds on you and you can apply in different circumstances. [Verifiable credentials] are facts about yourself that you control. So I don’t want this to be seen as digital identity – this is the next evolution.”

Andrew Bud, CEO & Founder, iProov

Verifiable credentials offer a path forward which does not build on foundational identity regimes or replicate the lingering exclusion gaps of such systems. Many of the emerging COVID credential regimes being developed internationally are indeed utilizing verifiable credentials, most notably the Common Pass, developed with support from the World Economic Forum, and the COVID-19 Credentials Initiative led by the Linux Foundation. Other organizations and initiatives utilizing verifiable credentials for such purposes include Microsoft’s Smart Health Cards Framework, IBM’s Digital Health Pass, Apple and Google, the International Air Transport Association’s Travel Pass, and CLEAR.

Source: w3.org

However, verifiable credentials don’t solve authentication issues alone. International travel may actually be easier than domestic regimes on this front, as travelers are typically carrying passports with them. Domestically, while IDs may suffice, iProov’s Bud, whose company made its mark in the biometric identity industry with its facial verification technology, views integrating facial verification with credential regimes as one valuable option to meet the requirements of high security, low inconvenience in authenticating identity to facilitate every day commercial interactions. With facial verification, all that is needed for authentication is a face and the credentials — no foundational ID required, without any other personally identifiable information disclosed.

However, as Israel’s case shows, reliance on single forms of identification would invite exclusion of those who receive COVID credentials outside of such credentialing systems; Bud insists that facial verification regimes must be optional. The more options, the less exclusion that will result. To be sure, If verifiable credentials become the digital standard for COVID health credentials, then flexibility geared towards universal inclusion naturally will necessitate accepting credentials accessible to populations lacking in digital technologies: paper. Estimates put a quarter of Europe’s population at risk of exclusion in the case of an all-digital credentials regime. Especially as COVID credential regimes expand to developing countries, this need for credential flexibility — digital and non-digital — will only become more imperative.

The Political Means to Achieve Credential Dreams

The technology and guidelines exist to theoretically include nearly everyone in a way that preserves data privacy and security, but will that happen? And will Israel’s Green Pass regime be only the first of many iterations to come? As the latest COVID issue to be politicized — in the latest escalation, Florida’s governor recently banned vaccine passports — it remains to be seen whether the required coordination among domestic and international authorities will sufficiently materialize or if public outcry will metastasize. Undoubtedly, countries will implement varying rules conditioning access to commerce on possessing COVID health credentials, with potential surveillance dangers and discriminatory measures purposeful or otherwise likely to manifest in at least some corners; according to the UNHCR, only 57 per cent of countries developing national vaccination strategies included refugees in their vaccination plans. As the early Israeli example shows, the question also remains as to how selectively enforced or followed compliance measures will be once countries reach a level of vaccinations allowing for Israeli-style vaccine passport regimes — and whether informal inclusion mechanisms open the door to forms of discrimination.

There also remains the polarizing controversies regarding digital COVID credentials’ profoundly novel use case for identity credentials: as the gateway to commercial spaces which thus creates a behavioral nudge to get vaccinated. Although anecdotally many foreign worker and asylum seeker populations in Israel — who disproportionately expressed vaccine skepticism — were compelled to get vaccinated due to such pressures, these novel efforts are moving forward without clear data to back up its efficacy or detail its effects. Yet it is already clear the politically polarizing effect this behavioral pressure has, with pushback from populations in Israel as well as in Europe and the U.S., where COVID credential regimes are still being developed or debated.

Source: Nikkei Asia

This tension of personal liberties and public health is a political issue by now familiar to all in pandemic times, not a technological one. Although public identity schemes digital and analog have frequently had political repercussions, this behavioral nudging component of the emerging credential regimes poses something new. If what results is a hodge podge of fragmentary regimes and public subversion — the uneven enforcement of Green Pass credentials in Israel as the earliest example — COVID credential regimes may be viewed variously as more theatrical than affirmative or more commercially exclusive than enabling. The question also remains as to whether the hype will match its potentially limited use case; if commercial access conditioned on vaccination can only be enabled when vaccinations are discretionary rather than rationed — i.e., when all members of a population have had access to a vaccine for a reasonable time — then for how long does this really wield the intended effect? In Israel’s case, people have quickly moved on from the pandemic in their everyday life not long after the Green Pass’ implementation, with enforcement subsequently spotty at best. iProov’s Bud believes such digital credential regimes will last far longer than technically needed — up to three years — as a psychological comfort while populations reenter crowded society. Other populations may react differently to evolving developments as Israel’s, with different vaccination trajectories and cultural attitudes. But if Israel is any indication, then the theory undergirding COVID credential-reliant entry systems may not align with realities yet to unfold.

The much-discussed vaccine passport regimes may fizzle out to limited use cases or short implementation times. They may become a political or logistical disaster prone to exclusion, divisiveness and/ or noncompliance. They may also improve on early mistakes, facilitating commerce and nudging people to get vaccinated without involuntary or excessive exclusion. If the verifiable credentials model is adopted widely as a standard, with countries and the private sector following inclusive and flexible guidelines, then technologically it can serve as the foundation for a new, self-sovereign identity system making our data not only secure and accessible, but truly ours.

Of course, as with any politicized technological issue these days, the shape and success of forthcoming digital COVID credential regimes won’t hinge solely on the proposed technology and design undergirding them. It will be a political and social experiment that nobody has ever seen before. In the current atmosphere, “vaccine passports” likely won’t be the universally regarded hero, no matter the outcome. But if these proposed solutions lay the foundation for a more interoperable and secure era in identity management and distribution, it’s harder to argue against that.

Image courtesy of Lukas

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Beyond the Last Mile: Reconsidering “Rurality”

Data, Diversify, Distribute: Emerging Optimization Models