Bike Sharing & The Ecosystem Effect: China Versus The US

~8 min read

Last November, The Guardian made waves with photographs chronicling the “death” of an industry. Hanging above the pictures, the headline boldly claimed: “Chinese Bike Share Graveyard a Monument to Industry's ‘Arrogance’.” But just half a year after its 'passing,' the model has made a remarkable recovery. One of the two industry leaders, Mobike, was acquired in early April for a crisp USD 2.7 billion by Chinese on-demand delivery service Meituan-Dianping. And while the likes of Mobike (and other Chinese startups such as ofo and Meituan) flash impressive market caps or funding rounds, a high-level analysis offers some perspective.

Chinese internet giants Tencent and Alibaba are the true power players in this game of, as The Guardian put it, life and death. These two payment ecosystem behemoths are competing for the loyalty and undivided attention of China’s 772 million internet users. Tencent’s WeChat and QQ have a leg up as far as social media is concerned, while Alibaba remains the uncontested victor in personal finance with Sesame Credit and e-commerce with Taobao in tow. The mobile payments market remains split between WeChat Pay and Alipay, each with a 54 and 40 percent share, respectively.

Although most of these services are connected by mobile payments, each service feeds into the other, creating an “ecosystem.” When someone opens WeChat, for instance, she can — within what is ostensibly a chatting app — book a flight from Beijing to Hong Kong through LY.com, find a hotel on eLong.com and then make a restaurant reservation through DianPing (all using the WeChat wallet, of course). The various services funnel into one another, and consumers' ability to use all of them quickly and efficiently is slicked by the grease of a unified mobile payments system.

Overarching stakeholders in China understand that Mobike and ofo are part of this larger proxy war — one can’t unlock a dockless bike without an enabling mobile payments system. But, as these competitors enter international markets, commentators and investors fail to see the companies in the context of a broader ecosystem of mobile payments and services. Elucidating this context is crucial to unravel the potential of these startups in the U.S. As Mondato’s research and conversations with industry experts revealed, bike sharing will not survive as a basic mobility service. It survives as an access point for user data, food delivery, mobile payments and a host of other ecosystem services.

Different Market, Different Rules

No two markets are ever the same. Investors routinely acknowledge this when sizing up the expansion of an American multinational into China, often citing cultural, regulatory and economic differences as potential barriers. The reverse, however, (i.e. a Chinese setting sail to the U.S.), seems to raise fewer flags. Bill Maris of California-based venture fund Section 32 mused in a Wired article:

“Investors are hot on bike sharing because the Chinese companies have proven it can be a big business.”

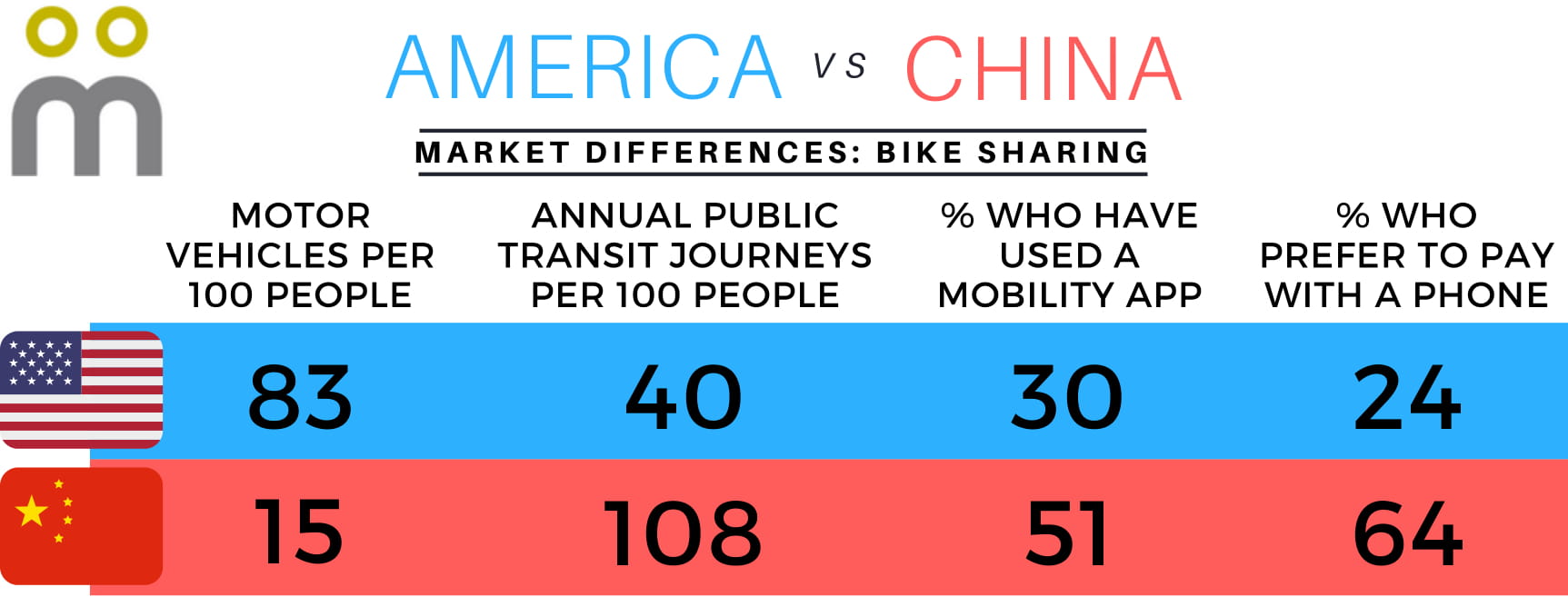

While we can rest assured that Maris’s firm conducted more rigorous due diligence than simply “it’ll work here because it worked there,” their decision to back San Francisco’s LimeBike is indicative of a market-blind approach that pervades the public discourse on dockless bike sharing feasibility. There still exist obvious structural differences between the U.S. and the Chinese market: notably, a less sophisticated mobile payments ecosystem and a potential slowdown in the equity necessary to buoy up bike sharing companies.

While these two issues are at the heart of the matter, other more peripheral points still factor into the odds of dockless bike sharing's long-term success. Chinese consumers are more willing and incentivized to use transport services than their American counterparts. Though China has a larger rural population than the U.S., those in urban areas are more condensed, thereby providing less reason to own a car and more reason to use public transit.

Rates of public transit usage are a significant 'shot-in-the-leg' for bike sharing schemes as it addresses the “last-mile” problem: getting somebody from the apartment to the subway, and from the subway to the office. Moreover, China is further along on the mobile payments curve (astutely satirized by the Wall Street Journal investigative dive, The Cashless Society Has Arrived— Only It’s in China), while it has been difficult for America to warm up to the prospect.

These factors have been borne out in usage data from early American forays into dockless bike sharing. Brad Bao, co-founder of LimeBike, an American bike sharing startup, pointed out on GGV Capital’s 996 Podcast that the average ride in China is 0.2-0.5 miles long, compared to 1.2 miles in U.S. For a model that thrives on quantity, not quality, of trip, this metric alone is problematic for firms like LimeBike.

Ecosystem Against Ecosystem

Bike sharing is simply one of the many strategies at the disposal of Tencent and Alibaba to drive users toward their ecosystems of payments, apps and other services. These platforms jump-start their own growth with the launch of “mini apps,” applications pulled from the cloud (rather than downloaded) that serve the dual purpose of freeing up storage space for users and forcing them to remain inside a closed payment loop. And while these mobile payment ecosystems have been widely covered, rarely do writers ask: do the ecosystems survive with the support of third-party apps, or vice-versa?

In some recent cases, developers have started making apps not for Google Play or the Apple App Store, but just for WeChat. That’s why entrepreneurs like Drew Kirchhoff — who founded a language learning app designed as a mini app — have called WeChat and similar ecosystem platforms “the beginning of the web all over again.” His app, Yoli, certainly would not have lasted without exposure to WeChat’s now 1 billion strong user base.

Mobile payment ecosystems are vital to the survival of bike sharing. Didi Chuxing, China’s top ride-hailing app, is one of just 8 mini apps listed in WeChat’s wallet section, making it more accessible than the general selection of over 580,000 mini apps. Mobike, Tencent’s prodigal son in the bike sharing industry, was also elevated to this status in March 2017. According to a report from Mobike, more than half (link in Chinese) of new users have come from WeChat since the service was integrated into WeChat’s wallet at the end of March.

The lack of a U.S. equivalent to Tencent or Alibaba equivalent is one explanation for the industry’s slow start in the U.S. Even though older payment systems could, in fact, accept credit card or cash at the dock, a scaled model, fully stocked with bikes scattered throughout a city, relies on unified mobile payments infrastructure.

With nearly 11 times more mobile payments processed in China than in the U.S., the U.S. faces the extra hurdle of building out a useful mobile payments architecture. But, mobile payments are not the only ecosystem tie-in and glue sought by the big Chinese players. Ofo, for instance, allows users with a Sesame Credit (Alibaba’s credit rating app) score over 650 to rent bicycles without a deposit. Indeed, service interoperability leads to adoption.

Whose Bikes Are They?

More important for Mobike and ofo’s continuity and growth has been finance acquisition. As of yet, none of the bike startups have named profitability as an immediate goal. While high costs and low revenues are normal for early startups, the failure rate of even some of the strongest bike sharing companies could spook investors, and cast doubt on the industry’s long-term viability.

Bluegogo — the former third wheel of the Mobike-ofo duopoly - which accounted for 600 thousand bikes, 20 million users and 300 million daily rides bikes, folded in November 2016 as capital dried up. As the CEO explained in an open letter (link in Chinese) following the company’s bankruptcy, venture capital simply disappeared as investors clammed up. Any capital that Bluegogo received was no match for the market leaders’ reserves. Indeed, the reports of a $3 billion equity purchase in ofo by Alibaba left Bluegogo’s total $90 million raised, well, the appearance of one blue bike in a sea of yellow and orange. More than 34 other hopefuls followed Bluegogo’s path to the brightly-colored bike graveyard.

Mobike and ofo are funded by Tencent and Alibaba because the giants desire popular, public add-ons. These firms obviously wouldn’t funnel this kind of cash into a completely hopeless industry, but it also is not a coincidence that venture capital firms, whose interests lie more squarely in investing in startups that vow monetary return, have lost enthusiasm even as these ecosystem companies ramp up funding.

Didi Chuxing’s participation in funding ofo is another strike against dockless bike sharing's case as a standalone industry. Didi has taken part in four of ofo’s eight funding rounds and reportedly owns a 30 percent stake, but similar to Alibaba, it has more than just ofo’s success in mind. The ride-hailing firm has launched its own bike share platform after swooping up the remnants of Bluegogo, and could be using its influence as an investor to constrain ofo. As Eva Xiao, a Tech In Asia reporter, pointed out on Twitter, ofo and Bluegogo bikes are now accessible via the Didi app but are not labeled as “ofo” or “Bluegogo;” they are instead seamlessly integrated into the Didi experience. Didi is not funding bike sharing because it believes in the industry, but rather to stave off a potential competitor from its own last-mile transportation services. Uber made similar moves in the U.S. with Jump.

Didi’s in-app bike sharing option totally obscures Ofo And Bluegogo branding (they’re the only two services that have integrated for now). They’re all Didi bikes now 🤣 pic.twitter.com/umgR3cT1jV

— Eva Xiao (@evawxiao) January 17, 2018

Survival or Extinction?

American bike share firms are still in the early stages of funding. Most have only taken flight as of 2017, and venture capitalists are still bright-eyed and engaged. If this funding begins to fall off as it did in China, however, who will the LimeBikes or Spins of the U.S. turn to as their benefactor? Could Facebook or Google jump in to save the fledgling industry? Probably not, and even if they do, an industry that struggles to get riders even with rock-bottom prices or generous handouts cannot forever live on venture capital alone. The costs from vandalism (a big problem in cities like Dallas), alone, have pushed Mobike to raise prices in the U.K.

The lesson here is not that bike sharing is “doomed to fail in most American cities,” as Motherboard asserted - a nuanced takeaway if there were any - but rather that it ought to be understood in the context of other services. In Mondato’s conversation with Roelof Opperman, a Principal at prominent LimeBike backer Fifth Wall Ventures, the venture capitalist emphasized the partnerships Fifth Wall facilitates between LimeBike and various real estate companies to which also fall in Fifth Wall's sphere.

LimeBike’s base service is of course important, but it is amplified, strengthened and even facilitated by partnerships. Access to capital was most certainly a barrier to entry for the 35 and counting failed Chinese bike companies, and Opperman laid bare the necessity of a continued lifeline of wealthy investors, which in this case could be the big American tech companies.

It is still far too early to pronounce dockless bike sharing either dead-on-arrival or the next big thing. The services have encountered trouble in France, across America, and even in China, but ofo itself did not hit its stride until two years in. This industry remains untested, but until it is, the experience in China shows that the only successful firms are those that can quickly move beyond wheeling out a bike.

Image courtesy of paul.wasneski

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Global Findex 2017: West Africa Steps Into The Spotlight

Do 'Cash Machines' Have A Future Without Cash?