To P2P, Or Not To P2P? Is That The Question?

~7 min read

Once upon a time, person-to-person (P2P) payments were, to all intents and purposes, mobile payments. Before there was M-PESA and MTN Mobile Money, creative and enterprising people in central Africa were sending mobile phone top-ups to each other as an easy and secure way to digitally transmit value. And in the days when mobile phones were feature phones, and not handheld computers with cellular functionality, that meant that GSM networks became a potentially new set of payment rails that were available to the billions of unbanked around the world.

And while that remains true, the decade since the launch of the first iPhone and the subsequent rise of cheap smartphones has once again transformed the paradigm, not just for the unbanked but for consumers in developed economies, for whom their smartphone is both an indispensable tool and the primary gateway to their digital identities. This has created an opportunity for a whole array of actors in the tech space to enter the fray, but in many respects their ambitions remain the same as those who have been toiling away in Kenya, Tanzania and elsewhere for a decade now: how to move customers beyond P2P payments and into a digital payments ecosystem that would see funds recycled and not cashed-out.

However, the difficulty in successfully making that transition has been highlighted in both Africa and North America, where payment platforms still largely function as either P2P or P2B, but rarely both. And while companies like Paga in Nigeria are making some inroads in bridging the gap between bill payments and P2P, and in Zimbabwe the country's cash crisis has created its own unique dynamic, overall, that elusive tipping point where mobile money deployments become mobile payment systems has remained out of reach.

Elusive Tipping Point

Similarly, in advanced economies, particularly the United States, no-one has come up with the right mix of product, design and engineering to create the killer app that allows people to send, receive and spend money in a seamless and frictionless way. So while Venmo (now owned by Paypal) is making a push into offline retail, and Apple Pay is dipping its toe into P2P with Apple Pay Cash, neither's expansion has managed to excite their users in the same way that caused their early adopters to become evangelists for the cause.

A major part of the problem is the fact that the enemy remains King Cash. In fact, the success of each of these products, in whichever market, at performing a niche function simply accentuates the fact that while cash is not perfect (and it does a very good job at keeping its costs hidden from the consumer), overall, it still emerges on top in most consumers' assessments: it is trusted, ubiquitous, reliable and has almost no barriers to use. So while there may be specific circumstances in which the functioning of cash can be improved upon (e.g., remove the awkwardness from asking for money that is owed? Use Venmo! Send $50 to your cousin across the country for her birthday? Use SquareCash! Pay for those groceries when you have forgotten your wallet? Apple Pay! Buy those concert tickets from Craigslist? Paypal it!) as of yet, no one app or wallet checks all the boxes quite as readily as cash does.

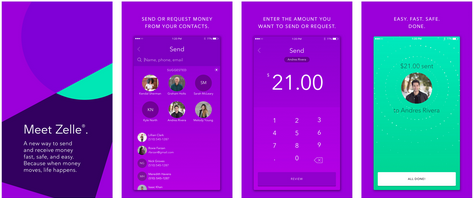

The operational niche of each of these solutions, and the risks, largely for consumers, in moving beyond them has recently been underscored by the curious case of Zelle, the somewhat late-in-the-day play by a consortium of major U.S. banks to get onboard the good ship P2P. Zelle (somewhat ironically, given how many U.S. consumers feel like hostages of their bank, the German word for a cell) is the successor to ClearXchange, an earlier attempt by U.S. retail banks to mimic the P2P success of Paypal by making faster payments using phone numbers or email addresses as proxies for account information.

Payment Zellots?

Somewhat predictably, ClearXchange was available as a premium product, and equally predictably was a failure, as customers saw little value in paying to have money arrive the next day into a friend or family member's account, having used their phone number or email to deliver the money to them. Cash, a cheque, Venmo or even Paypal were all generally cheaper and/ or better options.

Zelle has been something of a surprise success story and, contrary to ClearXchange's weak numbers, has been moving serious money in barely more than the year since its launch, capitalizing on its presence embedded in users' own banking apps (though it also exists as a standalone app). In 2017, Zelle users transmitted US$75 billion, more than double that managed by Venmo, previously seen as P2P's pin-up poster-child.

Notably, however, these numbers don't seem to have had a significant negative impact on Venmo itself, whose 2017 numbers were significantly up on its $20 billion transacted in 2016. And after spending a few years being the prettiest belle at the ball that no-one wanted to dance with, Square's Cash seems to have finally gained traction in 2017, boasting 7 million active users in December of last month.

Banks have leaned heavily on the security aspect of Zelle, promising that its payments are fast and secure (implicitly, just like cash), but without the need to visit a bank or ATM.

So... I did this @Zelle commercial. Y'all wanna see? #sureyoudo #howmoneymoves #ad pic.twitter.com/oon3fM5Wdf

— Daveed Diggs (@DaveedDiggs) January 14, 2018

Unfortunately, however, some unfortunates have been discovering that Zelle works a lot like cash: once you hand over your money, it is gone. Consequently, fraudsters have exploited how Zelle works to scam people out of their money. Zelle's response on social media has been little more than a "better luck next time" admonition to make sure to only use the product to send money to family or friends. And while the problem could be put down to user irresponsibility, Venmo experienced an equivalent problem of reversed transactions, before the company introduced more robust protocols for dealing with fraud.

It's possible to look at this as if consumers want the best of both worlds: the instantaneous nature of cash and the fraud protection of a credit card, but the reality is that cash-in-hand, literally, is popular for a reason: to take it back someone has to prise it from your grip. Scams where fraudsters can have transactions reversed or cancelled, and money removed from people's accounts without them even knowing, are the sort of pain points that if we lived in a world where all payments were electronic, someone would invent cash to overcome them.

The QR-ious Case Of China

The very glaring exception to this situation is in China, where Alipay and WeChat Pay have between them created a digital/ mobile payments ecosystem that successfully spans the whole panoply of payment functions from P2P to bill pay to offline shopping. And while the e-commerce, social media and gaming presence of their respective parent companies (Alibaba and Tencent) gave each digital wallet an impressive initial toehold, both companies quickly embraced two other crucial elements that brought users onboard and kept them there: the availability of bargains and hong bao, the little red envelopes of money traditionally exchanged during Chinese New Year.

Setting up and funding a digital wallet can be a hassle, so the incentives need to be strong. The social feed of Venmo is attractive to some, while the trusted bank brands behind Zelle are enough of an appeal to others. But both Tencent and Alibaba managed to harness the attraction of free money, and there is hardly a stronger appeal for many people. If someone is owed money and is sent it via a format that creates hassle (i.e. a new app and its onboarding), that can create resentment.

But, if someone is gifted money, they will likely do whatever is required of them to get it, no matter how many sign-on screens are involved. By gamifying hong bao, WeChat and Alipay got customers to entice each other onto their platforms with free money, and encouraged them to stay by offering discounts on things such as taxis, if ordered using the respective wallet. They also had an array of use cases lined up, once customers were onboarded, and just needed a few nudges to convince them to try them out.

This then is perhaps the secret of P2P, and what has set China's market apart from almost everywhere else in the world. China's digital wallets created immediately obvious value for customers to sign-up and to start using them, making sure not to leave obvious gaps where alternatives such as cash were able to creep in and disrupt the new habits. But while free money is an attractive proposition, few companies have the resources to create that sort of offering, or an addressable market the size of China's that makes the bet worthwhile. Nevertheless, China has shown that digital wallets 2.0 need to break out of their bunkers and niches, even for P2P transactions, and offer users a more full menu of ways to spend their money, otherwise they may remain siloed ad infinitum.

Image courtesy of Monito

This post was updated on 3/1/18

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Digital Identity: The Private Sector Takes Aim

International Remittance Hubs: Interoperability Evolving