Central Bank Digital Currencies

~7 min read

Bitcoin hasn't even celebrated its 10th birthday, and yet in that short space of time cryptocurrencies have gone from being a fringe topic of interest in the outer reaches of cryptography and libertarian subreddits to being a major matter of interest to central banks and governments around the world. Some governments, or independent national central banks, have even gone so far as to initiate discussions about whether to launch their own digital currency. Venezuela, admittedly under rather unique and unenviable circumstances, has already done so. So are Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) now inevitable?

CBDCs: Sanction Busters?

The first question that needs to be asked then is why would a country or central bank have an interest in establishing their own digital currency? The answer partly depends on the country is in question. Venezuela, for example, has rolled out the Petro, supposedly backed by the country's significant oil reserves (the worth of a petro will be pegged at the cost of a barrel of the country's oil), in an effort to evade U.S. sanctions that have choked the country's access to the world's money markets. Russia is said to be interested for similar reasons, but has judged such a project to pose too big a risk to the country's banking system (but allegedly facilitated the design and launch of Venezuela's Petro as an experiment in how it might work). Iran is believed to observing closely for similar reasons.

But beyond these countries that are cut off to varying degrees from the international finance system, central banks, particularly in Europe (including the Bank of England, Norway's Norges Bank, and Danmarks Nationalbank) and Asia (the Monetary Authority of Singapore), have been doing significant preparatory work on why and how they might eventually launch their own CBDCs largely as matters of academic debate. Sweden's Riksbank and the People's Bank of China, however, are actively exploring the possibility as part of their broader drive towards becoming cashless societies.

At one level, the question of CBDCs almost seems like a moot one. As readers of Mondato Insight will no doubt know, increasingly our finances are largely digital: we bank online and use payment cards or mobile devices to the point that carrying cash seems like an unnecessary burden. Nevertheless, we all expect that if we were to want some cash, or indeed to want to withdraw all our money from the bank in cash or a draft, the bank would have to be able to give it to us. And when customers start to worry that a bank will not be able to fulfill that elemental function, that's when you get a good old-fashioned run on the bank, as was seen in the U.K. in 2007 with Northern Rock.

Risk of Runs

Indeed, Northern Rock is instructive as to why central banks have up to now had grave concerns about the effects of a CBDC on financial stability. The British mortgage lender financed most of its day-to-day operations through borrowing on interbank markets. When the U.S. subprime crisis caused banks to get nervy about institutions that looked over-exposed to the property market, Northern Rock's main source funding ran out, causing the bank to haemorrhage capital and in short order go bust.

One of the main fears of central bankers, then, is that a digital currency, which by its very nature can be moved at great speed, could facilitate a run on not just a bank, but the country's entire banking system, like Northern Rock but writ large. The fear is that a financial or political shock could cause depositors (who are essentially lending money to banks) to pull their money rapidly out of the banks' reserves and into the CBDC (in order not to be the last man standing in line during the bank run), causing a run on all the banks and/or making them insolvent.

In order to preserve stability between the two "versions" of the national currency, it may be necessary that a CBDC should bear interest, which could itself pose challenges to the national banking system. Should the public have direct access to the CBDC, and if so is there a risk they would shun banks completely and prefer to keep their funds gathering interest in the central bank or a digital wallet? Might consumer behaviour change in some fashion, such as hoarding CBDC, and use it as a reserve or some form of savings account rather than as a fungible currency, thereby reducing the money supply? Given the pressure on parts of Russia's banking system caused by U.S. sanctions, it is easy to see then why a CBDC is an unattractive solution for Russia to relieving that pressure: it could end up killing the patient.

But Venezuela, on the other hand, has basically nothing left to lose, given the near collapse of the Venezuelan national economy and fiat currency, the bolivar, that preceded the Petro's launch. Serendipitously for Venezuela's President Maduro, this all occurred just at the moment the crypto craze was going to the moon. But for most economies, the risks involved with CBDCs remain real, or perhaps even still unknown.

Principles to Reduce CBDC Risk

Although making clear that the Bank of England had no current plans to introduce a CBDC, a recent research paper from the BoE addressed these concerns by establishing four principles that the authors believe can reduce, though not eliminate, the risks posed to financial stability, irrespective of whether the CBDC has wide access (can be tapped directly by the public) or narrow access (access is restricted to financial institutions or similar).

Four Core Principles for a Central Bank Digital Currency:

- It pays an adjustable interest rate;

- It must be distinct from reserves and they should not be convertible;

- There should be no guaranteed convertibility of deposits into CBDC;

- It should only be issued against eligible securities, such as government debt.

In our recent paper we specify four design principles such that, to a first approximation, bank funding need not fall when CBDC is introduced, and the amount of credit provided to the private sector does not contract. These same four principles also address the risk of system-wide runs from bank deposits to CBDC... While these design principles address some of the major concerns about the financial stability implications of CBDC, risks remain. For example, even if bank funding and credit provision do not contract, the presence of CBDC may affect the stability of deposits, the composition and cost of bank funding, and the profitability of banks’ business models.

Clare Noone and Michael Kumhof, 'Central bank digital currencies — design principles and balance sheet implications'

Even so, for a "normal" unsanctioned economy that is not Venezuela or Russia, are there sufficient, tangible benefits that would merit such risk, even at a reduced level? Or is this just faddishness, trying to keep central banks connected with the cool (but volatile) kids making waves with crypto? A 2016 working paper, also from the Bank of England, attempted to estimate the macroeconomic impact of a CBDC, and its authors concluded that it would have a positive impact on economic growth, though not one that is likely to dramatically change the nature of the conversation about CBDCs:

CBDC issuance of 30% of GDP, against government bonds, could permanently raise GDP by as much as 3%, due to reductions in real interest rates, distortionary taxes, and monetary transaction costs. Countercyclical CBDC price or quantity rules, as a second monetary policy instrument, could substantially improve the central bank’s ability to stabilise the business cycle.

John Barrdear and Michael Kumhof, 'The macroeconomics of central bank issued digital currencies'

CBDC =/= Blockchain

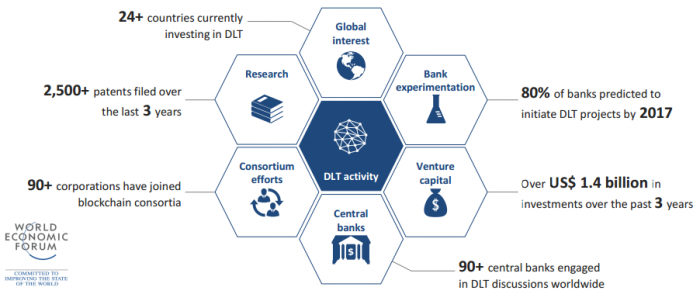

This 2016 paper assumed that Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT, basically blockchain or something very similar) would form the backbone of any such CBDC, but fast forward two years and that is no longer necessarily the baseline assumption -- an indication of how much things have moved (up and down) for cryptocurrencies in the past two years, including a greater awareness of bitcoin's scalability and capacity problems.

Current estimates are that bitcoin can can process between 3.3 and 7 transactions per second; a 2017 estimate from the Bank of England estimated that the U.K. would need a CBDC that could process several thousand transactions per second at peak times. This has led to the fairly sensible proposition that if it is decided that CBDCs are desirable, then the system should be designed to achieve the necessary and specific outcomes, rather than simply trying to piggyback it onto current DLT.

Which brings us back to the Petro, a "cryptocurrency" launched by a government that has nothing left to lose. The Maduro government in Caracas has claimed that the Petro's pre-sale raised US$735m, which seems unlikely, but given the talismanic effect of the word "blockchain" it is not entirely impossible. But the fundamental problem is that the Petro isn't really a cryptocurrency, or a currency of any sort, and is more just an elaborate method of funneling hard currency into the Venezuelan national treasury while evading U.S. sanctions on the basis of promised future oil revenues, which you can't actually access with a Petro (it can only be used for paying taxes to the Venezuelan state, so as an asset it is essentially worthless unless you are a Venezuelan taxpayer.) And, naturally, this hasn't endeared it to other central banks, for whose bankers the potential of DLT to evade regulation and control causes them to wake up at night screaming.

So in truth, we remain a long distance from making CBDCs a reality. The attendant risks associated with poor planning or implementation mean that even a 3% boost to GDP may not be a sufficiently attractive benefit to make the adoption of a CBDC worthwhile. However, for countries such as Sweden, in which there exists a certain amount of political will to phase out cash completely, then the cost-benefit analysis may change. The People's Bank of China too has declared its interest in launching a CBDC "as soon as possible." However, as things currently stand, blockchain or other DLTs are unlikely to meet the system requirements for a robust CBDC, meaning that the technology for, and thus the reality of, a CBDC seem to lie some decades off into the future.

Image courtesy of the World Economic Forum

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Satellites: Remote Sensing Is For Remote Customers

MENA: A Digital Finance Desert Or Oasis?