Financial Inclusion: Chutes And Ladders?

~7 min read

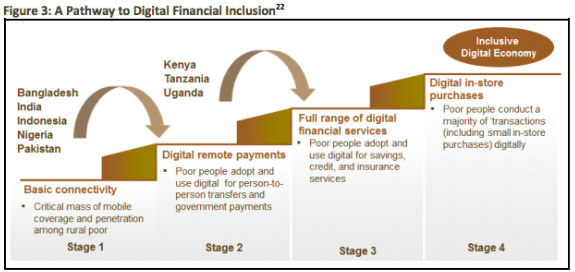

Financial inclusion at the base of the economic pyramid has often been conceptualized as a sort of ladder - with the digital finance and commerce (DFC) tools that enable it as the scaffolding rungs. In this framework, users without access to formal banking services gain access to and familiarity with a first product, typically mobile money, before experimenting with other, more advanced use cases on ‘higher rungs’ of the ladder.

Yet this view of DFC usage and financial inclusion more broadly elides the messier and more complicated pathways that characterize adoption of digital finance tools. How accurate is the ladder model of digital adoption? For development actors constantly evaluating the impact of financial inclusion initiatives and DFC players attempting to ‘upsell’ clients more sophisticated products, what moves the financially excluded from one DFC use-case to the next?

Recess On The Playground

Back in 2013, CGAP characterized the pathway to broader digital financial inclusion at a country-level as progressing from a first stage of widespread mobile coverage and penetration among the rural poor to a second stage of adoption of peer-to-peer digital and government payments. This logic and its narrative continues to be used not only by market watchers like CGAP in 2019 but also by sector participants tackling financial inclusion like Juvo and Destacame. Yet even without having to make the argument that according to this model’s logic, electricity access powering mobile phone usage may as well be seen as the first step to financial inclusion, some cracks emerge with the view of mobile money as the “first step.”

Source: A Digital Pathway To Financial Inclusion, CGAP 2013

While mobile money does have a critical role in promoting financial inclusion, there are in fact a plethora of other DFC use cases that are arguably the real drivers ushering users into the digital finance arena - use-cases both more ‘advanced’ and ‘basic’ (like lighting) than mobile money. Indeed, the past two decades have seen a slew of DFC and financial technology companies (fintechs) grow in markets without widespread mobile money adoption - and in fact, in many cases have been seen to drive its uptake rather than the reverse.

The Chinese example provides perhaps the most striking example at scale: Alibaba and Tencent, both pioneers in the e-commerce space, have on-boarded millions of buyers into the digital payment space since the early 2000s, and today have become major players in the retail financial services market. Bangladesh offers a potential follower: informal commerce facilitated by social media digital platforms like Facebook, Whatsapp and Viber (described as ‘f-commerce’) is driving impressive growth - in particular among women and the rural - in digital finance usage, while in many African countries, the demand for reliable lighting and the need for energy companies to securitize their assets through PAYG models have been demonstrated to drive both mobile money adoption and higher revenues for mobile money operators.

The importance of geography in this dynamic cannot be overstated: the fundamentally different states of play across sites make assessments of adoption drivers difficult to generalize. The reality is that, for any given market, DFC players and financial inclusion advocates must work with what is available. In some regions, this might be an overabundance of smartphones; in others, smartphones paired with widespread social media. Some areas can leverage good electricity access, or widespread telco agent networks; still others, developed credit offerings, digital identity solutions and high or low-tech microinsurance.

With such dramatically varying playing fields, perhaps a better metaphor than a financial inclusion or DFC ladder would be that of a playground: each market a different pen where not only are ladders, slides, monkey bars, swings and slides being built, but people begin using them far before their construction is complete. With this (admittedly more chaotic) representation of digital finance usage, we may gain a better perspective on the variety of pathways - and tumbles - which the financially excluded mull over with their cash in hand.

The First Rung?

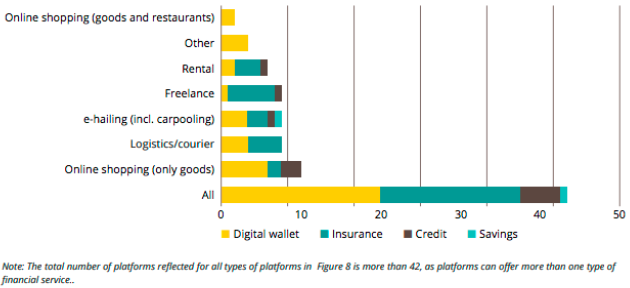

Historically, domestic P2P transactions were the lead products for all mobile money systems. But today, even the drivers for mobile money adoption have diversified: in a 2005-2018 study of online platforms (tracking African analogs to tech unicorns like Airbnb, Uber, Amazon and Upwork), 277 platforms were identified across eight countries, and here again e-commerce emerges as the dominant use-case luring users into digital finance usage. Thus, we see that use-cases traditionally considered ‘higher’ along a financial services ladder are often the pull factor that lead them to other DFC usages - and it is often this first touch-point which informs their appetite for other digital finance forays.

Source: i2i 2018

It is important to note, however, that trends in supply do not necessarily accurately represent demand; while insurance providers are particularly well represented among the platforms distributing financial services, for example, this does not by itself indicate if policies are being bought as well as sold. Furthermore, the majority of these models largely rely on web access through smartphone, tablet or computer ownership, which remains low in some markets.

Another critical element to the start of a new user’s digital finance journey is the support they receive. Despite all the friction which digital models promise to erase, there still does not appear to exist an authoritatively superior model for promoting financial inclusion tools than in-person training, particularly at the last mile. In China, for example, nearly one million third-party retail agents operate on behalf of a financial service provider to target the less digitally-literate, often the rural, poor or elderly. This model is being emulated in India specifically targeting women, with Grameen’s “friends of the village” program seeing a network of over 200 skilled agents help 270,000 mostly low-income women access to digital financial services right at their doorstep.

The model of Sokowatch, a startup facilitating small and medium enterprises (SMEs) FMCG procurement and restocking through digital services, provides a further African example, again in the e-commerce space. Agents, incentivized through commission, travel by motor-bike or matutu within the ‘recruitment zones’ in which they live to demonstrate to retailers in person how to order new stock at the push of a button. This example in particular illustrates the importance of leveraging the dynamics of trust in existing social networks (online or off) - in this case, the local, human face to a digital service. One could say that in getting users to take a leap of faith across the digital / physical chasm and onto the digital finance playground, the importance of developing trust between individuals, before trust in technologies or even brands - is all-important.

No Wrong Way Up, Or Down

If a variety of use-cases drive digital finance adoption, what drives movement between use-cases? While little quantitative data exists on this ‘use-case mobility’, a number of in-depth, ethnographic studies exist that elucidate some of the motivations for uptake. Research tracking the daily transactions of low-income households illustrates that while the poor exhibit remarkable creativity in overcoming the financial challenges they confront on a day to day basis, the shocking volatility of income - (from developed countries to the US) - often means that short-term opportunism characterizes much experimentation.

The case of Sokowatch provides more grounding illustrations relevant to DFC players tackling financial inclusion in emerging markets. Daniel Yu, the Chief Executive Officer of Sokowatch, is confident his company has cultivated the largest network of retailer relationships in East Africa, in terms of provisions delivered to shops on a daily basis, many of which are informal. Asked about what behavioral changes he has observed in the shopkeepers and small business owners Sokowatch works with, Mr. Yu points to concrete savings in time and money, but emphasizes how data-driven relationship building continues to generate new use-cases within their model:

“We have observed that shops that transition from SMS to ordering through our app exhibit significant increase in volume orders - so it makes sense for us to look at piloting a program where we finance a [basic] smartphone at low or zero interest to the shop, with our app pre-installed. We would be the first app the shopkeeper ever uses.” - Daniel Yu, Chief Executive Officer of Sokowatch

One insight poignantly illustrated by this dynamic is the way that use-cases split and loop into one another - and into various kinds of financial inclusion. This is a helpful reminder not to view financial inclusion through too rigid of a lens; the insight that credit offered to poor households is predominantly used to smooth living expenses rather than increasing wealth shouldn’t diminish the importance of increased financial resilience of households, in the way that a rubber band’s elasticity is as important as its size.

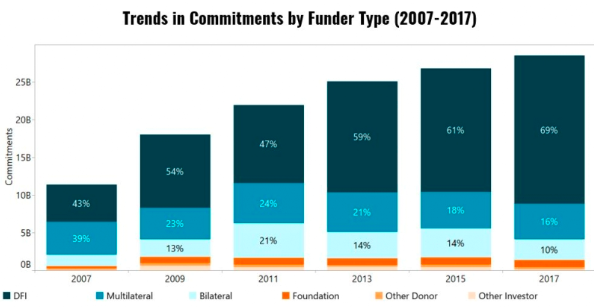

Another is that it may not always be appropriate to seek evidence of impact at the individual or household level at all; as digital financial systems are the embodied mobility of capital across a networked system, the impact of any intervention is likely to be dispersed through the system. It is particularly important for the sector to address this narrative - and its implications on evaluation methods - given that Development Finance Institutions’ importance to the DFC funding universe continues to grow (see below).

Source: CGAP 2019

It may be useful to reframe the ladder narrative as specific to use-cases: once a user is using loan products, they indeed may build credit history to access greater amounts, or switch providers of a similar use-case based on preference or value.

Playing With Others

It is clear that the applications of mobile money intersect with a much larger set of DFC use cases, most of which address real problems with demand proven by a range of informal workarounds. Synthesizing the demands for disparate use-cases should thus be seen as the fastest way to achieve widespread financial inclusion: a world where providers of financial services gain increased accessibility through the collective efforts of the ecosystem in getting more users access to the digital finance playgrounds - and better, faster, safer tools to experiment with. For Sokowatch envisaging an asset-finance play to feed back into their order numbers, what could a partnership with smartphone financing specialist Aspira yield?

So rather than set up simplified metrics of financial inclusion, the focus should be on building linkages between providers to create the maximum number of opportunities for the financially excluded to explore their own unique digital finance pathways. Encouraging interplay between DFC use-cases would be one way to link the different playgrounds together, creating opportunities for access with agency - which may one day come to represent financial inclusion more than the adoption of any single digital finance product.

Image courtesy Agathe Marty

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Microfinance Institutions: Prospects For B2B Fintechs?

Proof Of Address: The Invasive Species Of KYC