King Cash in the Congo: A Tale of Three Cities

~10 min read

Throughout much of the developing world, the availability and use of digital finance services have become the norm rather than the exception. Yet enormous pockets of financial exclusion persist in large part because, in certain markets, mobile money has failed to overtake the allure and ease of “old-school money” — cold hard cash. The consequence of a financial system still solely using physical fiat, however, is persistent inequality of access to financial services, tools and products. The Democratic Republic of the Congo represents one massive such ‘King Cash’ pocket, with less than a third of its 90 million strong considered “financially included.” Much ink has been spilled on the reasons why mobile money takes off in some places and not in others — but behind the generalities, trends and truisms lies the reality that each space has its own unique story. This week’s Insight takes a tour through three cities in the eastern Congo to take stock of the challenges, risks and opportunities in dethroning King Cash.

Cash in the Big City

Cross the border from Rwanda to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) at the Grande Barrière, and you may be impressed by the high-ceiling, marble-imitation linoleum and general cleanliness and orderliness. Present your documents, first in the Rwanda queue to exit, then the Congolese to enter, and if everything is in order, you’re on your way to experiencing one of the most jarring cultural transitions: from the staid, reserved, and orderly Rwanda to the dynamic and chaotic Congo.

The transition across the Petite Barrière, not a mile further north, is a smoother transition. This is where the locals pass, and the barrier is more fluid — yet, in contrast to many other border spaces, you can’t really spend Congolese Francs in Gisenyi, Rwanda, nor Rwandan Francs in Goma, DRC. And even though MoMoPay is fairly ubiquitous between individuals, formal and informal businesses in Rwanda, the Congolese across the border overwhelmingly prefer cold, hard cash.

Naturally, stacks of Congolese bills are fine, but particularly in eastern Congo, what smells even better? “In God We Trust:” US-denominated greenbacks. ATMs abound in Goma, the provincial capital — but so do error messages. Expect to spend a couple days finding out which local banks inexplicably reject your plastic, which ones grace you with only a $200 withdrawal ceiling, and which ones charge you $15 in withdrawal fees. Learn to wake up early because the ATMs run dry of cash, and that goes for the dedicated USD dispensers and their Congolese franc counterparts; they naturally come in pairs for customer convenience in this dual currency context.

Money moves in the Congo, and lots of it; stacks of hundred dollar bills make for cleaner logistics, but given that $5 dollar bills are the lowest denomination accepted (and generally only for bills printed after 2006), you’ll end up wasting time and money on every little transaction unless you also stock up on tattered 1,000 Franc notes (~50 US cents) — necessary denominations for facilitating small transactions along Goma’s volcanic rock-pebbled streets.

Be careful though — don’t assume your bills from abroad will pass like butter here. The slightest tarnish, rip, or tear, immediately spotted by the practiced eye of a gas station attendant or shop owner, will lead them to reject your bone fide, Treasury-issued $20 like an intemperate bank teller. Or, accept a mark-down for your slightly tarnished bill, as this, in turn, will be the terms from the cash exchangers who await in flocks at busy intersections. The government has recently issued a directive to accept $1 bills, but so far, no dice. At the end of the day, the functionality of a given medium of exchange is, fundamentally and concretely, what the people will accept.

Cash, Culture, and Connections

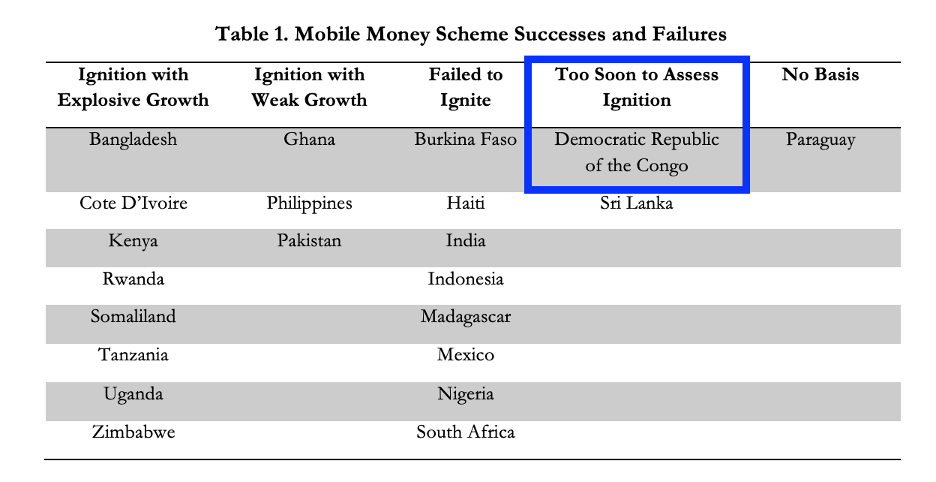

A 2015 study of why mobile money “ignites” in some countries but flounder in most frames the Congolese digital finance story in a nutshell: we’re still in chapter 1. Against the backdrop of a succession of authoritarian leaders’ post-independence, two wars, and several banking system collapses during the 80s and 90s, the mobile money ecosystem is still in its infancy, with most pointing to 2012 as its genesis. Growth in the 10 years since has been significant, with an average of 20% year-on-year additional subscribers, but low active usage. Yet pace the main roads of any market, and you can’t go 20 meters without seeing a “Cash Point” agent offering transfers from a familiar cast of characters: Vodacom, Orange, Airtel, Tigo.

Source: University of Chicago, 2015

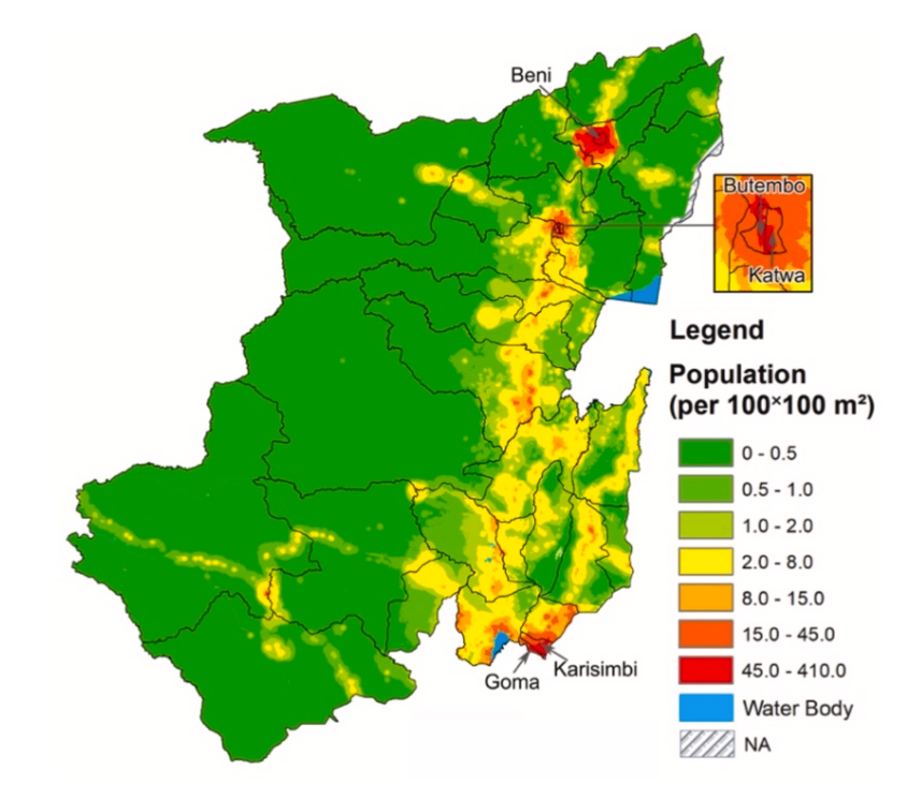

A contradiction emerges: mobile money appears both ubiquitous and under-utilized. This, of course, is only the perspective from Goma, which, by Congolese standards, is deeply cosmopolitan; indeed, few of the million-plus ‘Gomatriciens’ are originally from this business, NGO, and United Nations armed forces (MONUSCO) hub, perched atop the serene-looking but methane-filled Lake Kivu. Most are emigrants from the North Kivu province, rich in agriculture, natural minerals and armed groups. In the lingering mistrust of the formal banking system, mobile money has emerged as a viable method of getting money from city to village, and within these linkages emerge a feedback loop; mobile money breeds rural-urban mobility, facilitating not only evacuations under troubled circumstances, but also the exodus from subsistence agriculture towards more city-centered occupations. Such trends are not unique to eastern Congo; recent empirical evidence utilizing the experimental introduction of mobile money in Mozambique document an “increase in migration out of rural areas when mobile money is available.”

Source: Goma, Virunga National Park

Bills in Beni and Butembo

Prep your dollars and francs if you are headed to the airport. Like the rest of the city, the Goma airport is perpetually under construction, and in the hectic, tightly-packed, and unmarked passage between security screening, ticketing, COVID check, security payment and bag-drop, you will have many opportunities to offer ‘coffee money’ — bribes — to new ‘friends’ facilitating your progression to the single-gate waiting room. Like many aspects of the Congo, it may seem inefficient, and it may be stress-inducing, but if you’re accompanied and you’ve prepared the little bills that unlock each step along your passage, it all happens very fast.

You board a twin-engine turboprop and take off over the world’s second largest rainforest after the Amazon, a region which at the moment is experiencing renewed armed conflict from rebel groups. You land in the Mavivi airport just north of Beni Ville, the smallest of three “cities” in the province, one that is scarce in paved roads, but plentiful in both NGOs and UN peacekeepers. Reliable statistics on population size are rare, but at least several hundred thousand souls live in this city of crossroads.

You have a payment to send to a doctor in the downtown center of Masisi, one of the six provinces closer to Goma, so you stop at a local kiosk. The agent, a portly man in his 40s accompanied by his wife, takes the transferee’s number down in a notebook from within the metal bodega-like enclosure. They’ve been doing mobile money transactions for several years now, “from the beginning,” in fact. “Airtel was the first here, before M-Pesa. They are still number one in the city,” he remarks. $30 dollars are sent; $29 are received, and the agent shows his feature phone to confirm the transaction. The commission is 12 US cents, but he does a lot of volume.

“At the end of the month, depending on the month, the commission can come to 300, even 500 dollars. Sometimes $200 for Airtel, $100 for Vodacom, $30 for Orange.”

Beni mobile money agent

How do they manage insecurity, you wonder? “Here in the city, we’re good,” he says. “Sometimes we’ve been threatened, but where we are here, it’s okay, and we can go inside.” He gestures to the backdoor, to the prime spot along the busy street, a main thoroughfare off of which the side streets spill outwards.

You take an hour-long drive down to Butembo, the second-largest city in the province. Here, the population approaches a million, and though much more ethnically homogenous, it is an important commercial center possessing the Chinese factories that big-time local merchants do business with. Here, too, dollars dominate. Row after row of wooden cots populated by money changers depict the face on the US $100 bill, Benjamin Franklin, jauntily and across an inspiring spectrum of fidelity to the original.

Source: Photo by Sam Miles

It’s a seriously bustling city — packed. Thousands of motos stream by along the main road; a woman sells shoes with one perched on top of her head, another strolls by balancing a tray of four or five severed goat heads. There is noise during the day but calm at night, heat but also frequent fog and cold. You hear international hits blaring from radios, ads for local energy drinks from megaphones. You see urban destitution, village-women hauling kilos of charcoal strapped to their backs and foreheads and an infant in one arm, and stylish fashionistas all pacing the same streets.

Another transfer to make — you walk not 20 meters from your lodging before encountering a mama in her 50s sitting at a red-painted desk bearing the names of the telltale transfer options. She’s been an agent for five years, and the relative peace in this city, compared to Beni’s proximity to insurgents, has helped the construction industry sprout four- and five-story glass buildings. It costs $51.50 to send $50 via M-Pesa. You pay in cash, and after returning your change discretely from a plastic bag underneath her desk, she makes 13 cents commission, which adds up to $100 for her in a good month across all the operators. Nairobi seems to be the prime international destination here, illustrating how differently woven even similar and proximate cities are within the regional and global fabric.

Source: Population distribution in North Kivu Province, eastern DRC, Applied Geography (2015)

Both in Beni and Butembo, you find RawBank ATMs, which, despite the higher withdrawal fees than, say, Bank of Africa, have gained the widest geographic footprint in their decade-long rise to the top of the Congolese bank fray. There are no withdrawal problems here, surprisingly — the cash flows quickly from the first try. Here as well, however, most locals use Airtel for one-off Cash-In/Cash-out (CICO) and Western Union for larger amounts where liquidity may become an issue. A sign advertising the benefits of Illico Cash, RawBank’s flagship e-banking solution, is prominently displayed on the ATM, but no one you talk to, even the youth, are biting yet.

Going Digital in the DRC

For all the visibility of mobile money agents in the three cities, it remains challenging to assess just how well mobile money is progressing in the DRC beyond the oft-repeated line in the few reports that do exist describing active usage as “low.” GSMA’s 2014 report on mobile money in the DRC estimated the total number of transaction volumes at $30.7 million two years after its official “start” in the country, while a 2020 report on women’s financial inclusion in the Congo cites Central Bank figures estimating total volume at $680.7 million. These are still relatively small numbers in the absolute (Kenya’s volume for comparison, sits north of $5 billion with 60% of DRC’s population). Yet the growth is undeniable, with potential for more.

Cracking the code to killing King Cash — or even putting a dent in his dominion — is a challenge many different Congolese players are working on. The government suspended taxes on transactions in March in an attempt to bring down costs; telecom operators are looking into novel hardware solutions for bridging the last-mile connectivity options that constitute mobile money’s ‘rails.’

Yet the situation is so dire that even some traditionally intransigent actors — banks — have taken the role of leading innovators. A Harvard Business School case study on RawBank’s Illico e-bank solution encapsulates the chicken-and-egg challenges of igniting mobile money in the Congolese context: you must innovate to make mobile money more useful to local populations, but local demand must justify expensive investments into a risky sector. For a player like RawBank, investing heavily in customer education to simultaneously pursue both online and brick-and-mortar offerings represents a “first-loser” dynamic, where competitors may benefit more from its efforts than Illico’s ROI may justify.

“Many players benefitted and still benefit from this cash-based economy. Formal and informal rules have been built upon the exchange of bank notes. This is a well-known situation...[but] a focus on a small number of discrete, prioritized business cases must be made. The eastern region of the DRC seems like a good place to start, influenced by more advanced economies like Rwanda or Kenya. The rising middle class in Kinshasa or Katanga should also be priority targets.”

Thomas de Dreux-Brézé, Head Of Strategy and Project Management at Rawbank, interviewed in forthcoming Harvard Business School Case by Lauren Cohen and Grace Headinger

Ten years after the introduction of mobile money in the country, it may still be too early to make the call on whether digital finance uptake and usage will ignite and take off or only sputter in select pockets. But the fundamentals so far, despite all the well-documented challenges facing the country, do look good on the whole: four years after the country’s first democratic election and peaceful transition of power, overall GDP growth has rebounded fairly well after the global COVID shock, averaging 5.7% in 2021.

And all the while, through the rebel flare-ups, through the under-the-table mining contracts, through the global pandemic — the population works, they travel, they sell and trade, and while many slip lower into poverty, others still prosper. The local businessmen with a bit of capital smile the most, as they have a real sense of the costs of doing business and how to limit them. In this lies perhaps a bit of wisdom to start dethroning King Cash in the Congo; in a place where good data — nay, even basic, accurate and up-to-date information — can be rare, it is those with the deepest knowledge and widest networks who are best positioned to reap the benefits of the unevenly rising tide of digital cash in Congo’s high-risk, high-reward city streets and village markets.

Image courtesy of Ivan Diaz

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Integrated Solutions: The Sole Path To Sustainability And Scalability?

Vietnamese Fintech: Sprinting Before Walking?