Small Scale Series: Island Hopping Across the Caribbean

~8 min read

Approximately 45 million people spread out over 7,000 islands, 13 independent countries, 20 territories, six official languages, and too many pristine beaches to count — so are the numbers underpinning the struggle for scale in the Caribbean. Reflecting its location spanning the oceanic crossroads of the Americas, Caribbean fintech doesn’t really have a singular direction or identity at this juncture. It’s more like a composite of tiny scale strategies straddling diverse markets tailored to their language, colonial history, and migrant corridors. With the region’s governments often behind the times on regulations and taking different approaches to digital finance altogether, the Caribbean is evolving more into fintech fiefdoms than a unified market.

A Disjointed Affair

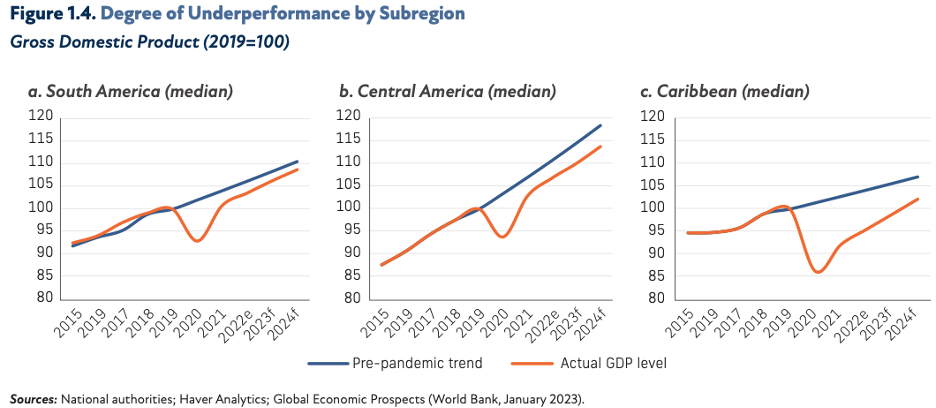

The Caribbean, along with Latin America, already stands out for its lack of integration with global markets. According to a recent World Bank report, Latin America and the Caribbean struggle with a lack of diversified economies and underperforming trade levels compared to the rest of the world. The Caribbean in particular struggles to forge strong economic ties globally — hurdles that persist as local economies still recover from COVID’s impact on tourism.

In the case of tiny markets in West Africa, neighboring large markets like Nigeria and Senegal have provided avenues for fintech imports or, as in the case of small-scale success stories like Gabon, a roadmap for scaling via export. Yet finding some large, centralizing “node” for an exchange of capital, services and knowledge in the Caribbean context isn’t so obvious. Out of the Caribbean’s population of approximately 45 million people, about 75% are concentrated in three countries: Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. None of them serve as natural focal points for regional scale-up efforts. French-speaking Haiti continues to face one of the worst economic and political situations in the world, and Cuba’s command economy remains to a large extent in a bubble of its own.

With a population of 11 million that is quite small in absolute terms yet in Caribbean terms a behemoth, the Dominican Republic in recent years has shown some promise as an emerging hub, with about 68 fintechs by the end of 2022 after averaging 129% year-over-year growth from 2017-2021, according to the IADB. Sectors experiencing growth include digital payments, alternative finance options like digital lending and invoice factoring and even insurtech.

Yet aside from Cuba, few countries in the Caribbean speak Spanish. Inés Páez leads the financial innovation and inclusion team for the Dominican Republic’s financial supervisor, the Superintendencia de Bancos, while serving as the president of the executive board at Fintech LAC, an IADB initiative to foster the development and integration of fintech markets in Latin America. Paez notes that several fintechs in the D.R. have sought expansion in markets like Guatemala or Panama rather than fellow Caribbean markets.

“Our fintech ecosystem has experienced significant development, making us one of the benchmark markets in Central America. However, language remains a critical factor.”

Inés Páez, Head of Innovation and Financial Inclusion, Superintendency of Banks of the Dominican Republic."

Páez emphasizes three areas of particular challenge in the D.R. context: facilitating the conditions to export solutions to Latin America so that fintech companies can scale, overcoming chronic problems in financial and digital education, and fostering innovation and the participation of new players. However, Paez acknowledges that despite efforts to enhance access to financial services, cash-heavy markets in the Caribbean — often reliant on tourism or offshore activities — face difficulties due to scale and informality, which limit financial inclusion initiatives.

“We talk a lot about financial inclusion, and many initiatives claim to have inclusion as their objective, but we must measure the real impact that is achieved... sometimes inclusion-focused products may not be economically feasible or attractive for traditional intermediation entities, but they could present opportunities for fintechs depending on their business model.”

Inés Páez, Head of Innovation and Financial Inclusion, Superintendent of Banks of the Dominican Republic

Seeking Scale Abroad

Yet compared to regional neighbors, the Dominican Republic is positioned far better when it comes to issues of scale. Most Caribbean islands number less than one million people. In some cases, diaspora communities — and the remittances they generate — can outnumber the totals back home.

One such case is tiny Belize, where several factors have made it hard for digital financial services to take root. With only 400,000 people and a GDP per capita of just over $6,000 — and a different political and linguistic tradition than its Central American neighbors — Belize’s financial services sector is underdeveloped. According to Michael D. Young, a Belizean American entrepreneur and founder of Belize Fintech LLC, some closed-network ATM cards— but no debit cards — are available among the country’s handful of banks and credit unions, and only three basic digital wallets have reached the market.

Digital money transfers between banks and credit unions are impossible, and a lack of remittance options have forced remitters to resort to money mules or Western Union, says Young. Within Belize, the market isn’t any more efficient, as financial service companies often cannibalize one another; at one restaurant in Belize, there may be three separate card terminals from three different banks. Interoperability is absent where no efficiency can be wasted.

Efforts to kickstart — and enable the requisite scale for — digital financial services in Caribbean contexts like Belize’s often rest squarely on connections to diaspora communities in places like the United States. Young is spearheading Belize Fintech, a digital payments provider that seeks to wed a digital wallet with an ATM card attached to Belize’s largest credit union. For Young and his business partner, Vishal Sharma, making a successful fintech product in tiny Belize will be inextricably linked to ties in the diaspora, with future hopes for Belize to be a test pilot for produt export elsewhere.

“The only way we can scale is by actually targeting the diaspora in the United States. There's about the same amount of [Belizeans] in the [United States] than there is in Belize.”

Michael D. Young, CEO, Belize Fintech, LLC

There is evidence that linking corridors with advanced economies and fintech hubs like the United States does have its economic and knowledge benefits. According to a World Bank report, “North-South” trade agreements between Latin America and more developed economies have provided far greater benefits than “South-South” trade agreements; the 110 bilateral trade agreements embedded in the Latin American Integration Association provided GDP contributions equal to the benefits accrued by Mexico under NAFTA alone.

Look-Alike Vistas, Different Rules

Especially in certain English-speaking Caribbean markets, there have been some cases of digital financial solutions spanning several markets within the region. Shared market characteristics isn’t necessarily reflected in regulations, however.

“The Caribbean people do share a lot of common interests, there's a lot of cultural similarities… but the biggest challenges are each of these markets have a very different regulatory environment. Navigating what the laws are in Trinidad versus what the laws are in St. Vincent versus St. Lucia versus Barbados — it is all a different market.”

Christian Stone, CEO, Term Finance

Stone runs Term Finance, a digital lender based in Trinidad & Tobago yet operating in six Caribbean markets, focusing on consumer and SME lending. Local banks in the Caribbean have often been among the most profitable ventures in the region, capitalizing on their positions as offshore havens while operating with little competition from international banks to reap high margins — if to the detriment of inclusion efforts and digital innovation.

And in the Caribbean, the lending space led by banks is highly collateralized. Stone says only 8% of the population in Trinidad & Tobago can access a bank loan.

Caribbean countries with a retail payment system (shaded purple)

Source: IDB

While differences in regulations pose the largest barriers to expanding across the region, Stone says that once they’ve been adjusted to the particular regulations of a given country, Term Finance’s products have been essentially readymade for the consumer base across English-speaking Caribbean markets. Digitized operations greatly aide expansion by allowing Stone to keep operations centralized in Trinidad. According to Stone, this has allowed Term Finance to become profitable, with Term Finance recently purchasing Barbados-based lender Fast Cash to become possibly the largest digital lender in the Caribbean.

“Because the markets are so small, we want to keep our overheads as low as possible and try to create as much operational efficiencies as we can.”

Christian Stone, CEO, Term Finance

Tripping Over Each Other’s (Tiny) Toes

While Term Finance’s strategy has hinged on lean overhead costs with expansion across English-speaking Caribbean countries, it can still be difficult to get the region’s governments to keep up the pace to allow inter-Caribbean markets to flourish. Efforts like CARICOM — a political and economic union of 15 states in the region — have failed to produce sufficient market integrations, says Stone.

“There's been 50 plus years of talk of regional integration — the argument, of course, is ‘hey, we’re only a few 100,000, maybe a million on the island. If we come together, we'd be so much stronger.’ But I think that's a lot easier said than actually done.”

Christian Stone, CEO, Term Finance

On the one hand, rivalries between regional governments set the tone, beginning with questions of who becomes the regulatory standard-setters without a clear market leader. Issues of scale itself can make it harder for true regional integration, and Stone offers the example of a four-hour flight from Trinidad to Miami costing less than a flight from Trinidad to Barbados nearby.

Sagging efforts for integration have extended to some of the regional government’s efforts to incorporate either blockchain technologies or CBDCs such as the Bahamas’ Sand Dollar and Jamaica’s Jam-Dex. The peculiar nature of island governments deciding regulations upon the influence of several policymakers has created a situation where most of the region has no blockchain-enabling regulation at all — while countries like Bermuda and the Bahamas enact bespoke regulation to welcome blockchain startups and even crypto behemoths like FTX.

FTX’s Bahamas-based bust offers a frightening cautionary tale for a Caribbean banking sector already plagued with de-risking, but also one that hints of the potential for the tiny markets’ regulatory outlooks to alter course rapidly depending on a well-placed policymaker or two at the vanguard, like what happened in Bermuda and the Bahamas.

But empowered regulatory visionaries might be the exception to the rule. Extending policies or initiatives across borders has likewise proven uneven. DCash is another digital currency created by the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank to enable seamless payments in seven of the eight Eastern Caribbean countries. However, inter-regulatory squabbling and technical issues have mitigated its interoperability capabilities and plagued functionality. Digital payments in the Caribbean in general have lagged without the requisite market integration to make economies of scale take place in these cash-heavy societies.

Sluggish regulatory updates manifest in several directions. Tiny populations mean less revenue and less staffing for regulators to keep up, and in the case of regulators and especially from the banking sector, the old guard is often still in power — clutching to a conservative, risk-averse approach.

As Stone sees it, this only reflects the slow-paced life in the sundrenched Caribbean. Whether regulators can get their act together to foment true regional integration and innovation is a question they’ve yet to answer in the affirmative. But as success stories like Term Finance prove, even in fragmented, sub scale markets, expansion and sustainability — with operational efficiencies facilitated through digital means — is possible when so many (percentagewise) remain financially excluded from traditional means.

Image courtesy of Hugh Whyte

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

South Africa: A Model Of Stability Or Stymied Innovation?

Post-SVB: Are Emerging Markets Digital Banks’ Oasis?