Out Of The Shadows: How B2Bs Are Reaching Informal Sectors

~8 min read

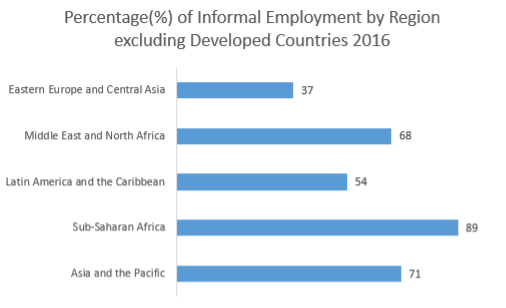

The informal economy is a dynamic yet inefficient ecosystem consisting of laborers, small businesses and gig workers, comprising a whopping 89% of total employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Offering software and more, vanguard B2B platform-based businesses are assisting micro-businesses by unifying supply chains and promoting greater efficiencies. Despite informal merchants’ poverty levels and lack of education — and their lack of concrete operational data — platform-based B2B companies are managing to increasingly capture the informal economy while providing merchants an initial pathway towards financial inclusion.

Source: ILO

Hacking The Social Networks

The informal traders’ industry may look haphazard to the outsider: the temporary shops, the unpredictable mid-day closings in cases where inventory runs out, or the seemingly random item purchases that are difficult to analyze without modern digital tools. Serving such informal ecosystems through B2B propositions requires first an understanding of the strong social networks and interdependencies underlying informal markets and their supply chains. Typically, small-time informal merchants purchase their orders from suppliers with whom they have social relationships.

“I go to buy onions from Marikiti (a local open market in Kenya) [from] Mama Charles’ stall…if she’s closed, I’ll buy wherever my [fellow small shop owner] friends recommend.”

Wanjeri, Fruits and Vegetable Vendor, Kiambu, Kenya

Socially oriented business relationships in informal markets are ubiquitous across Sub-Saharan Africa, and emerging B2B platforms have taken note. Like the mobile money revolution that came before, some B2B firms create a network of local agents who utilize their social networks to onboard merchants onto the new platforms. Among those employing this model is Marketforce, a B2B ecommerce startup that connects distributors, retailers, and manufacturers by providing a software system to manage the retail distribution operations across different stakeholders in Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda.

Other B2B platforms leverage pre-existing relationships between suppliers, logistics providers and the small-time merchants. Under this model, B2B firms work to onboard the distributors and logistics providers in the ecosystem first and then proceed to the retailers who work with them, as is the case with Omnibiz, a Nigeria-based B2B ecommerce firm that handles logistics of packaged food items, beverages, personal and home care items.

“Change management in mass markets is very difficult to execute, let alone ones with such strong social structures. When you change something drastically, adoption becomes difficult. That’s why we are not working towards a change; it’s a transformation where the existing process is transformed [by] making it more efficient.”

Deepankar Rustagi, Founder, Omnibiz

For companies starting from scratch, like Twiga Foods, an agricultural produce and Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) supply platform, it takes time to achieve requisite levels of adoption through pre-existing social relationships. One vendor in a small neighborhood marketplace in Gachie, Kenya speaks of how Twiga Foods agents and drivers sometimes pass by her shop to ask if she will purchase fruits and vegetables from them; she sometimes does if the price is lower than her usual supplier. Through constant interaction with the Twiga Foods brand, trust slowly builds as merchants turn into buying clients.

“There are a few things that are key [to hacking the social relationships in informal trade]. First, we offer undeniable value to our customers. The prices — at the end of the day, restaurants want to make money. They are not in the restaurant industry only because they love to serve; it’s a business… [With] the combination of providing superior value to restaurant owners and also helping some of these existing relationships do things more efficiently, we’re seeing people being more comfortable switching over to us.”

Njavwa Mutambo, CEO, TopUp Mama

Cognizant of the small margins these merchants operate in, Twiga Foods, Marketforce and other platform based B2B companies offer informal merchants their software free of charge. A merchant can order products through the provided app, after which the company will send products to the merchant, providing doorstep delivery. For some of these platforms, a minimum number of products or total cost of goods is required to complete an order. For instance, Omnibiz has a $50 minimum order amount for every order made, while Twiga Foods sets a certain number/size of items per order, such as 20kg of onions per order.

“Unified purchasing power enables optimized distribution and minimizes logistics costs for us, enabling us to provide free logistics for the merchants and quick turnaround time. What we will see in the next couple of years is that we may do away with these caps as we scale and aggregate demand.”

Deepankar Rustagi, Founder, Omnibiz

Navigating The Distribution Bottlenecks

The largest inefficiencies in informal channels lie in the supply chain. Goods sold in the informal market tend to go through several layers of brokers, with each layer introducing a higher markup on goods that results in exorbitant prices of goods sold to informal traders. Fragmented distribution prevents a one-stop-shop for products, with merchants having to interact with several different suppliers for multiple products. Simon, for instance, a merchant that sells packaged items alongside fresh fruits and vegetables in Dagoretti, Nairobi, Kenya, gets his beverages from one supplier, bread from another, and his vegetables from different wholesalers in the open market that’s approximately five kilometers from his shop’s location. Inventory management becomes quite the task when the tools available are merely pen, paper and a good memory.

The bottlenecks are felt among manufacturers, distributors, and logistics teams as well. While some of the FMCG supply chain is formalized, a significant part is operated informally as one goes down the supply chain to the neighborhood stalls, kiosks, and hawkers. This informal part of the supply chain often lacks clear data points to accurately estimate order size and patterns. Characterized by a widely dispersed and variable network of small and micro-merchants, the secondary market often faces inconsistent order sizes and purchases. Most informal merchants resort to making guesses that can be quite off, resulting in numerous losses in which excess vegetables rot and packaged products end up expiring on shelves — or, conversely, they run out of items needed by clients.

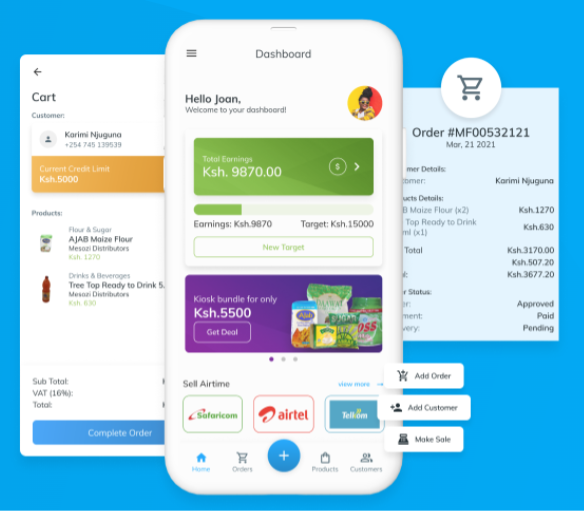

B2B platforms in the industry are smoothing out these bottlenecks by upgrading the merchants’ pen and paper resources to digital tools that keep reliable records and reduce the time spent on inventory management. Through the B2B firm’s software, merchants can access multiple products from several suppliers and distributors in one platform, cutting the time spent dealing with different stakeholders. They then access logistics assistance tools in which goods are delivered to their doorstep, eliminating the need to close up shop in order to restock items.

Alice Wambui is a fruit and vegetable merchant in Kiambu, Kenya that uses Sokowatch and Twiga Foods’ platforms. Through these platforms, Wambui went from closing her shop every other day in order to restock fresh vegetables to being able to remain open daily. No longer needing to wake up at dawn to get the highest quality items at the informal market — or carrying them by herself — she can now open her shop earlier, eliciting greater margins and efficiencies for her small stand.

Some B2B platforms, such as Omnibiz, go the extra mile for small-time merchants by enabling insights on the performance of goods based on the frequency of orders made and other data points for business growth. Likewise, the logistics providers, manufacturers and distributors get a platform where the informal traders’ activities can be mapped out and patterns derived from the data collected. The platform-based companies derive their income from commission off the supplier’s margins, offsetting the free software provision for retailers.

Source: Marketforce

Yet offering the software for free isn’t enough for these small-time merchants living on the economic periphery to see real growth and inclusion. Private lenders are notoriously averse to servicing informal businesses due to their high-risk profile and lack of sufficient collateral, with limited information on the individual’s business and their ability to repay loans.

B2B platforms seek to address such financial issues in several ways. First, there is the top-up now, pay later feature that allows traders to order items on credit, which TopUp Mama, a B2B marketplace for small restaurant owners in Kenya and Nigeria, employs. The feature does come with the risks of merchants failing to make payments after the sale of goods taken on credit. Tesh Mbaabu, Marketforce co-founder, mentions that where digital financial products are involved, Know Your Customer (KYC) checks become necessary. Marketforce requires the person’s ID card documentation to avail these services to them. To lower the risk of debt repayment defaulting, platform companies are also utilizing data points accessible from the software to predict the payment likelihood of individual merchants, akin to mainstream digital lending. Through merchants’ transaction patterns, they can be given a credit score, according to Mbaabu. A recently completed pilot study by Marketforce found less than 1% of its users defaulted on their loans.

By assigning merchants a credit score and having their transaction records all in one place, B2B companies like Marketforce are proving crucial for merchants to begin accessing loans and credit facilities from banks and other private lenders — a critical first step towards financial inclusion for the swaths of micro-businesses dotting Africa and beyond.

A DIY Ethos

With patchy telecommunication networks and poor road networks, last-mile provisioning of these services faces barriers across Africa. The solution, as Omnibiz’s Rustagi sees it, is to find a way around it — or do it yourself. In Nigeria, fintech players like Moove, which provides vehicle financing to clients, don’t wait for when the roads will improve. Rather, they find ways to make what is available work. Marketforce localizes their transport and logistics, sending out large trucks in areas with good roads and small trucks in areas with smaller, less reliable roads. Some also take calculated risks and build the infrastructure themselves from scratch. Twiga Foods, for instance, has invested in a fleet of trucks and cold storage facilities for agricultural products, which enables them to provide better value for rural farmers while delivering fresh products to traders in the cities they operate in. By eliminating several intermediary brokers through the supply chain, Twiga Foods can provide better prices to the farmers and directly sell to small merchants in cities while still earning a profit.

TopUp Mama has taken a different approach, leveraging the current supply chain that Mutambo, its co-founder, says is much more developed than it was years back. According to Mutambo, it isn’t necessary to source farm produce directly from small-scale rural farmers today. Considering the time and resources required to pull this off, TopUp Mama largely works with mid- to large-scale farmers and aggregators who source their produce from small-scale rural farmers. Some of TopUp Mama’s partner suppliers are within the Nairobi area, which eases supply side logistics and allows the startup to focus on providing small restaurant owners with value that includes easier inventory and logistics management along with competitive prices for products.

Slowly, the numbers of men and women shopping for produce before sunrise in Kenya are dwindling as supporting B2B companies witness growing adoption and funding. Twiga Foods’ app, ‘Soko Yetu,’ has over 50,000 app downloads on Play Store, while Marketforce has recorded over 110,000 onboarded members across Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda. TopUp Mama, in just a year of existence, managed to oversee over $2.3 million in sales on its platform and onboard 3,500 vendors. Competition is already fierce, with several small-time merchants admitting to having three or more market apps on their smartphones to compare prices and go for the option with the best value.

Following mobile money’s textbook approach to incorporating the formerly excluded, B2B companies servicing small-time merchants aren’t waiting for regulators to catch up — they are drawing informal merchants out of the shadows themselves.

Image courtesy of Laurentiu Morariu

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Smartphones In Africa: Reaching An Inflection Point?

Instant Payments: A Key To Financial Inclusion?