Does Demonetisation Work?

~5 min read

While the Indian government's dramatic and surprise demonetisation campaign garnered most of the headlines, India is not the only country in the world potentially headed on a path (however long it may be) towards a cashless society. Some analysts are already predicting that Sweden could be totally cashless as soon as 2030 (see the video below), but it is the country's banks that have led the transition. In China too, it is the private sector and the market that have catapulted that country into the top-flight of cashless-ready economies.

Is the future cashless? It is for Sweden, which could be completely cash-free by 2030 pic.twitter.com/BxCM4eqYBi

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) 12 July 2017

On the other hand, as in India, the governments of Rwanda and Turkey (among others) have plans for the dramatic reduction, or elimination, of cash from the economy. However, an inarguable lesson from the Indian experience is that dramatic demonetisation efforts by the government can cause significant short-term suffering, irrespective of any long-term benefits the may proffer. A more fundamental question, though, is whether such government-led initiatives are actually attaining their objectives. Worryingly for interested governments, the jury is still very much out.

Cowboys vs. India

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's assault on cash and the gray and black economy ("DeMo", as it has become known in India) was either a resounding success or a catastrophic failure, depending on who you ask. That probably means that it is much too early to tell one way or the other. In a country of India's size, complexity and (in)capacity, counting the winners and losers of anything presents unique problems, so it may be some time before a balanced and sober independent analysis becomes available. For that reason alone, any assessment that is not hedged and unequivocal ought to be treated carefully.

A recent article in Foreign Affairs branded demonetisation as "madness," and authoritatively observed that "there is little evidence that any of the criminals suffered more than temporary inconvenience." It's not certain, however, whether that is actually the case. The government offered a dirty money amnesty with an accompanying 50% surtax, and it is not yet known how much was brought in via this method.

The evidence currently available, in line with the general trend, points either to it being a big success or a big flop: 97% of the DeMo-targeted notes in circulation were exchanged by the year's end, so either criminals and tax evaders availed of the amnesty in surprising numbers, or were remarkably adept in circumventing a need for it. Either way, the government's expectation of three trillion rupees of dirty money not being returned proved unfounded; only about one sixth of this amount remained unaccounted for.

Of course, as Mondato Insight has repeatedly noted in discussions of fraud, it is an inevitable fact of life that will migrate to the path of least resistance. But disrupting criminal business patterns and money networks, even if just for temporary inconveniences, will lead to opportunities for both investigative law-enforcement agents and entrepreneurial criminals. Forcing criminals to have to change their ways of doing this is a goal in and of itself for police.

And while government ministers clearly do not constitute balanced and independent analysts, the Home Affairs minister has felt confident enough to link demonetisation to a decline in violent incidents in Jammu & Kashmir. But if you are a government minister in another country contemplating the cost-benefit of following India's suit, potential future advances in crime-fighting (the peculiarities of Kashmir aside) offer scant encouragement to undertake a massive disruption to the country's financial system.

Nattering Nabobs of Negativism?

Nevertheless, demonetisation clearly did have short-term effect on India's economic health, with some estimates (though not official ones) having GDP growth dropping by a full percentage point in Q1 2017 compared to the previous quarter. That is a far cry, however, from the description of an entire country "[grinding] to a halt", that was to be found in Forbes, for example. Similar voices reinforced the chorus from some commentators (who almost seemed to be willing Modi's "madness" to fail) that it was all for naught: disruption, despair, and even some deaths, in pursuit of populism and good press.

Undoubtedly, the drastic withdrawal of the Rs.1000 and Rs.500 notes had short term effects:

- The fast-moving consumer goods industry reported around 1%–2% reduction in volumes;

- Unilever experienced a 4% decline in sales volumes;

- Tractor sales were weaker;

- India’s largest car manufacturer, had a 3.5% increase in car sale volumes, down from 18.4% growth in the previous quarter;

- Scooter sales declined 22% in December 2016, compared to the prior December, marking the highest monthly contraction since 1997.

A prudent observer, however, might have waited for tax season before declaring demonetisation a flop. In just the past week the Indian tax authorities announced a jump of 25% in the number of Indians filing tax returns. It is, as of yet, unclear what the financial value of this influx of tax filings might be, but since one of the stated objectives of "DeMo" was to bring more Indians into the tax net by reducing tax evasion, it is clearly a promising sign.

The "nattering nabobs of negativism" haven't entirely had the field to themselves for long. Recent reports have pointed towards India's rural economy, particularly its micro-loan sector, bouncing back from the shock of DeMo that had pulled the carpet out from under it. Loan collection rates fell from 98% to 50% in some areas, but are said to be regaining ground, and should return to pre-DeMo levels before year's end by some estimates. A plumper harvest also worked to soften the blows of the PM's hammer-blow to the cash economy... but, not every government would get so lucky.

Cash Culture Revolution

While not impossible, it seems unlikely that other countries will follow Modi and India's path and launch a surprise attack on their cash economies. If for no other reason, few political leaders have the personal popularity and political capital that India's Prime Minister currently possesses, making such an audacious move nearly impossible. But there is a deeper issue that extends beyond the realm of politics, or even economics, and that is the cultural factor. Even if the destination is the same, cultural affinities and practices, particularly when it comes to something as fundamental as money, possess an importance that cannot easily be overlooked.

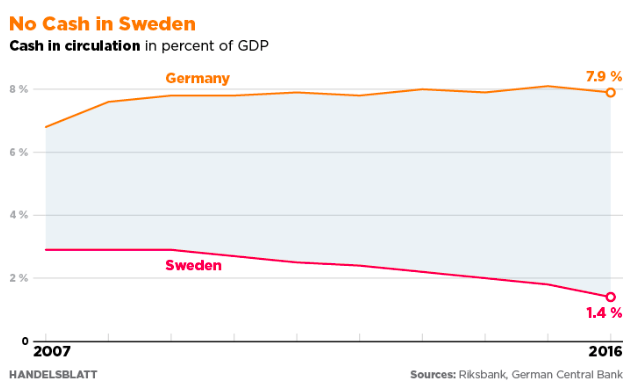

Take the examples of Sweden and Germany: two countries separated by a few hours sailing and sharing a common linguistic root are on shockingly different trajectories when it comes to digital payments.

Today, less than 78 billion Swedish krona (€8.4 billion) is in circulation, down from 109 billion krona just six years ago. Handelsblatt Global

Today, less than 78 billion Swedish krona (€8.4 billion) is in circulation, down from 109 billion krona just six years ago. Handelsblatt Global

Unlike in India, in Sweden the switch away from cash has been led by the private sector -- the banking sector working collaboratively to create tools for consumers that will entice them away from notes and coins -- that caught on much, much more rapidly than anyone expected. In effect, the Swedish banks were pushing at an open door because Swedish culture was ready to go cashless. By way of contrast, it seems clear that neither politics nor the market is going to entice Germans away from foldable euro.

But pointing out the cost of cash transactions is unlikely to impress Germans. To them, it’s not about the money, it’s philosophical. “We’ll still have cash in 30 years,” said Carl-Ludwig Thiele, a member of the board of the Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank.

So when it comes to the extremely ambitious plans of a country such as Rwanda, which hopes to go cashless in barely two-and-a-half years, skeptical eyebrows may be raised. Despite President Paul Kagame's near unanimous "re-election" in recent days, Rwanda has not the cultural inclination, nor its government the political popularity, to make the leap to being cashless in just a few short years, which would be a truly revolutionary transformation.

And therein lies the key: when you mess with people's money, you mess with one of the most fundamental aspects of their existence as citizens in the modern world. It is ground that needs to be tread upon carefully, for as much as any economic or technological shift, changing people's relationship with money requires a cultural revolution, and successful top-down examples of those are few and far between in human history.

Perhaps ironically, India's reputation for permanent controlled chaos served to its advantage in the context of demonetisation: India's beleaguered citizenry both embraced the goals of DeMo and have both the resilience and experience to enable them to weather such a man-made storm. Given their recent experiences with top-down cultural revolutions and government-fomented turmoil to the point of genocide, China and Rwanda's citizenry, for example, seem less likely to embrace monetary revolution.

Revolutions are tricky things to assess, but let's just hope we can arrive at a judgment on Modi's DeMo revolution sooner than Chinese leaders did on the French Revolution. When asked in 1971 by Henry Kissinger what was his assessment of the French Revolution, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai is reported to have responded, "It's too soon to tell." Hopefully in 12-24 months the jury will be in a position to return a verdict on DeMo.

Image courtesy of Scott Edmunds.

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

M&A Mayhem: Telling Up From Down

The Data Debacle: Insights Falling Through The Cracks?