Credit Bureaus: Resting On Their Laurels?

~7 min read

With the advent of alternative data, many lenders in emerging markets have side-stepped the barren vaults of Credit Bureaus and instead elected for third-party tech providers who have rigged up unorthodox data sources (utilities, telecom, rent, asset record, demand deposit account information, social networks, satellite imagery) as predictors of credit-worthiness. This strategy has fared particularly well when serving no-hit or 'thin file groups.' Juvo has cracked open the opportunity of airtime credit for mobile network operators (MNOs). FarmDrive, on the other hand, has broadened the addressable market of smallholder farmers for financial institutions.

These interventions of alternative data, however, are narrow in their application and non-transferable. Credit Bureaus still remain the 'institutional' solution, an aggregator of information that transcends siloed credit products, providers or industries. So, have Credit Bureaus lived up to this designation? How have they added to their database coverage, especially in emerging markets, and are they a capable party in institutionalizing alternative data?

A Public Good

The role of private Credit Bureaus, invariably, differs from that of public Credit Registries, which are tailored to the State's needs as a supervisor of financial institutions. For public Credit Registries, the priority is monitoring aggregate loan flows to inform prudential oversight and regulation, not value added services like credit scores. Private Credit Bureaus instead attend to commercial entities, which are more interested in individual profiles. Therefore, the sweep of data by Credit Bureaus involves smaller loan sizes, compiled from both financial (credit card companies, microfinance institutions) and non-financial (retailers) sources alike.

There are a number of well-documented positive externalities that follow the establishment of a Credit Bureau. In addition to bettering the performance of lenders' portfolios and contributing to the general transparency and stability of financial systems, Credit Bureaus ensure that consumers are not left to the mercy of financial institutions. When lenders are allowed to hoard away borrowers' data, it opens up a very real possibility of price-gouging.

"Open and transparent credit reporting benefits bank customers by promoting credit market competition. The exchange of credit information enables customers to build reputational collateral and to access credit outside established lending relationships. This reduces the ability of established lenders to exploit their privileged knowledge of clients’ credit histories." Global Financial Development Report 2013, The World Bank

Much To Be Desired

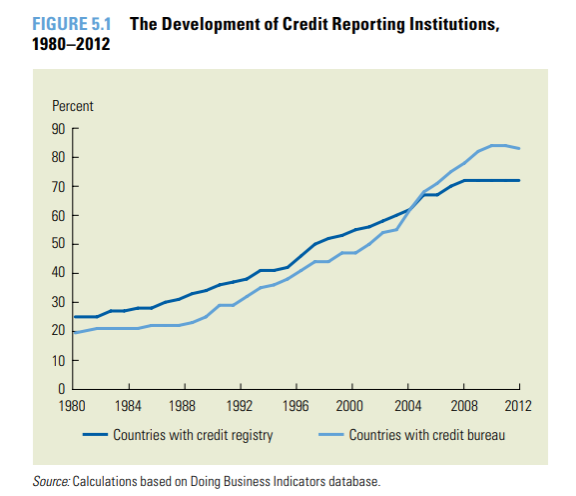

And yet, this provisional plus of Credit Bureaus is moot if such credit reporting infrastructure does not exist. Although there have certainly been waves of activity in forming credit bureaus since the 1980s (see below), gaps persist. Much of central Africa, western Africa and the Pacific Islands is still without, with no indication of change on the horizon, while others are in the most embryonic of stages. The Central Bank of Myanmar (CBM) issued its first Credit Bureau license last year to Myanmar Credit Bureau Limited, which is forecasted to be up and running by the end of 2019.

The bite of existent Credit Bureaus, however, is toothless if the overwhelming majority of the population is outside of their scope. The unveiling of shiny new credit scoring facilities is meaningless if it covers a tiny portion of a country's people, which is the case in far too often. Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Nepal and Niger are just a few instances where the Credit Bureaus account for less than 5 percent of credit applicants. When segmented by income globally, the disparities in Credit Bureau coverage become apparent: low-income (4.57 percent), lower middle income (19.62 percent), middle income (27.20 percent), upper middle income (34.19 percent), and high income (55.63 percent).

In light of the abysmal and asymmetrical rates of Credit Bureau penetration, of course lenders cut from a different cloth sought other courses of action to flush out their potential customer bases. Telcos restless to monetize mobile data, for example, tagged in Cignifi and Tiaxa to implement credit scoring analytics for their small-scale credit products. While this approach expands credit, it also strands consumers. It does not feed into a reputational collateral that can be leveraged outside of the now established lender relationship.

Credit Bureaus Clap Back?

Sometimes, small corrections that are far less flashy than alternative data can also right the course of Credit Bureaus (and Credit Registries, for that matter). Abandoning regulatory loan thresholds - or a minimum loan value required to be eligible for Credit Bureau reporting - 'miraculously' improves coverage overnight. This often compels data filing by microfinance institutions to the Credit Bureaus, whose clientele are disproportionately women and micro-businesses.

Along with widening breadth, there too is a regulatory quick fix to digging deeper into Credit Bureaus' databases. Credit reporting systems that only factor in negative variables, such as payment tardiness or default, but not positive variables, like payment punctuality, are less resilient. In Brazil, which molted its negative-only reporting Credit Bureau coat in 2011, a 2004 study concluded that the inclusion of positive data would have reduced the average default rate among the Brazilian banks from 3.37 percent to 1.84 percent. Concurrently, this same act would have, at that time, rendered 82 percent of the population lendable, instead of just 56 percent when stuck with only one stream of data.

The moral of the story, then, seems fairly straightforward. The more information awash in the Credit Bureaus, the better off the lenders and the borrowers. In emerging markets, the institutionalization of telco and utility data, while still in its infancy, is popularizing (the former is an especially tantalizing new alternative data source, given strong mobile phone penetration rates). Slightly ahead of the curve in this regard, in 2011 two mobile phone companies, MTN and Tigo, and an electricity and gas company, EWSA, first reported transactional data to Rwanda's Credit Reference Bureau, re-branded by TransUnion in 2015. As a result, there was a sharp, and immediate, 2 percent increase in coverage by the Credit Bureau.

The synergies between Credit Bureaus and MNOs are only further intertwining as MNOs look to graduate more subscribers from prepaid to postpaid and bump average revenue per user (ARPU). Cignifi, with the blessing of its telco partners, has provided Equifax access to its data reserves in Latin America. Pushed by similar business motivations, Telkom Indonesia adopted a more proactive posture with its data centre arm taking a 10 percent stake in Indonesia's first credit bureau, Perfindo Bureau Kredit, in 2016.

Hardly content to be left in the dust, the traditional big boys of credit scoring, Equifax (active in 17 markets), Experian (active in 19 markets), and TransUnion (active in 22 markets), are all investing in their own alternative data infrastructure, which has mostly materialized through acquisitions. Equifax purchased Talx, a specialist in employment and income verification, for USD$1.4 billion and IXI, a consumer wealth and asset analytics platform, for USD$124 million nearly a decade ago. Experian, instead, snapped up RentBureau in 2011 to aggregate positive and negative rent payments. TransUnion in 2014, meanwhile, absorbed L2C, an agnostic alternative data firm with expertise in unbanked pockets. (TransUnion markets its CreditVision Link Short-Term Risk Score, unveiled last year, as the 'the first and only score in market to combine both trended credit bureau data and alternative data sources').

Credit Bureaus very much imagine themselves to be the sun in this credit scoring solar system: a gravitational force strong enough to keep all other parties in orbital check. An intensifying interest in alternative data communicates similar intentions, a way to plug holes and further solidify Credit Bureaus' centripetal role.

“Alternative data sources (such as property, tax, deed records, checking and debit account management, payday lending information, address stability and club subscriptions) have proven to accurately score more than 90 percent of applicants who otherwise would be returned as no-hit or thin-file by traditional models.”Mike Mondelli, SVP of TransUnion Alternative Data Services

There are, however, still many stones left unturned in institutionalizing alternative data. Much of that hinges on regulation. What sorts of alternative data are permitted? TransUnion CIBIL, for example, is in preliminary talks with the Reserve Bank of India to authorize the collection of electricity, gas, telco and rental payment histories by Credit Bureaus. The regulatory seal of approval is, unfortunately though, only half the battle. Whether it be the merchants or the industrious third-party tech startups, people rarely volunteer their proprietary goodies for collective consumption. Such actions often require some 'cajoling': in the United States, there has been speculation over legislation rumblings that could turn into a mandate on reporting certain alternative data to the Credit Bureaus.

Starting Over

The concept of an institutionalized credit score sculpted by a neutral observer has value and, therefore, is here to stay. Who ends up as the custodian of that score - and the data behind it, alternative or not - in contrast, is less universal. In many cases, traditional Credit Bureaus may in fact be the best option to assume the rank of ringleader as data sources diversify.

But, that is not true in every scenario. Old-school Credit Bureaus in Brazil have struggled to transcend negative-only legacy reporting systems (recall above). Frustrated by an unmoved needle in scoring coverage, the five biggest Brazilian banks banded together to form Quod with the help of LexisNexis Risk Solutions in 2018. Quod is a fintech-sytle Credit Bureau that is born out of technology instead of shifting into it, enabled as it is by an open source, massively scalable, super-computing data platform. Most importantly, its out-of-the-gate emphasis on positive scoring payment habits hopes to better capture previously invisible Brazilians.

And then, there are situations where the blueprints of Credit Bureaus past are worth about as much as toilet paper. Sierra Leone's lone Credit Bureau serves 2,000 people, less than 1 percent of the country's inhabitants. Microfinance institutions calculate risk assessments internally, and none of its borrowers' information is churned into reputational collateral.

To remedy its problem of fragmentation and dearth of data, the government of Sierra Leone has partnered with the U.N. Capital Development Fund, the U.N. Development Program and Kiva to modernize its identity architecture through blockchain. As a starting point, the Kiva Protocol intends to digitize and log its partners' financial records (all of whom are microfinance institutions) to create a foundational layer for its citizens' financial identities. It is a radical approach to the construction of a Credit Bureau, but atypical implementers, like Kiva, could become more common as distributed ledger technology equalizes the field. For Credit Bureaus, now is not the time to get lazy.

Image courtesy of Experian Day

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Are Elections A Digital Litmus Test?

Can Insurtech Learn Best Practices For Selling To The BOP?