The Youth In Emerging Markets: A Segment At Risk

~9 min read

As international agencies and governments respond to the health and economic shocks of COVID-19 crisis, special consideration should be given to young people in the developing world. The young (defined as those aged 15-29) in developing nations were already contending with high unemployment pre-COVID; now, the pandemic is taking a particularly grave toll on the economic prospects of this group. In addition to being three times more likely to be unemployed, young people are overrepresented in the informal economy where they receive no benefits, making them doubly vulnerable. Young people in developing markets today enjoy fewer and lower-quality job opportunities, with the outlook darkening by the day. What can governments and interested organizations do to look after this all-important segment of the population?

Pandeconomics

High- and low-income countries alike are struggling with employment and the future of work as they post increasingly high unemployment rates and small businesses and factories shut down and announce layoffs. A growing number of studies have found that the world’s poor stand to be the hardest hit by the oncoming global recession. The United Nations predicts that at least 8% of the world’s population will slide into poverty as a result of the coronavirus in 2020, and this figure is based on the most conservative of the three scenarios outlined (in which the global economy contracts 5%). Importantly, this could be the first increase in global poverty since 1990, and the report writes that “such increase could represent a reversal of approximately a decade in the world’s progress in reducing poverty.”

The U.N. report also warns that regions where high poverty levels already exist, and where eradicating poverty has proven difficult, will be the most impacted. The economic shock of the pandemic has already hit many countries in these regions hard. In Bangladesh, for example, 7% of the Bangladeshi workforce has been laid off (primarily from garment factories).

To Be Young

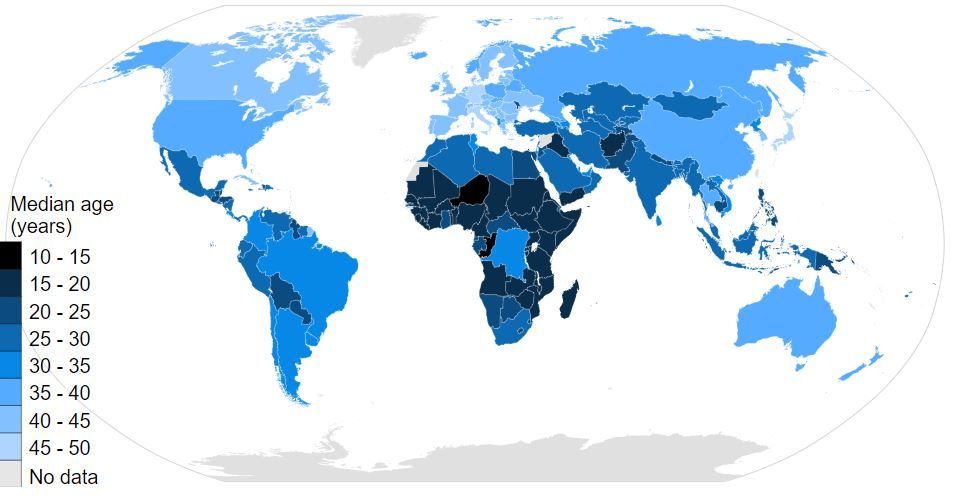

According to the International Labour Organization’s 2015 Baseline Report for Youth Employment Solutions, youth accounted for 40% of the world’s unemployed population that year. The problem of youth unemployment is worse in places where market growth doesn’t keep up with population growth, which is most often the case in developing countries in Africa and Asia. The report estimates that in order to have enough jobs for young people, 600 million jobs must be created this decade.

Source: Sarah Welch

The problem of youth unemployment is a crucial element for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal to eliminate poverty. Young people today won’t be able to escape poverty by 2030, the SDG target date, without adequate employment opportunities. But as things stand now, even when young people do secure jobs, they are more likely to join the informal workforce and forgo the higher salaries and benefits accorded to formal workers. This is especially true for women. Returning to Bangladesh, which has the highest gender disparity in terms of rates of informal work, it's been observed that 90% of young women who work experience vulnerable employment compared with 45% of men.

The COVID crisis should concern even young people who are formally employed in the developing world, because the sectors that are most at-risk are the same that employ the most young people. These include wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, administrative services, and hospitality and tourism.

Moreover, young people are more likely to be employed by SMEs, the businesses least equipped to withstand long periods of closure due to lack of liquidity ot access to credit. SMEs compose an average 40% of GDP in emerging markets, and that figure is even higher if informal businesses are included. They also provide 80% of employment in these economies.

In Africa, youth unemployment is already a major and multifaceted, economic problem. Although Africa has an increasingly educated population and now spends significantly more per capita on education, there continues to be a mismatch between the skills newly graduated young people have to offer and the jobs available in African economies. African youth stand to suffer considerably in the coming months as the International Labour Organization predicts 22 million layoffs in this year’s second quarter alone across the continent.

The African Development Bank reports that a staggering two-thirds of youth who are not in school are unemployed. Despite varying levels of economic growth and the creation of 3 million jobs each year, it is not enough to accommodate the 10-12 million young Africans who attempt to join the workforce every year.

Youth unemployment at such a massive scale is more than an economic problem--it is a social problem that could metastasize into civil unrest if neglected. At a Harvard Kennedy School Forum last spring, President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana conceded, “no one needs to tell us that massive unemployment of Africa’s youth is a ticking time bomb.” For context, the president referred to troubling recent events, like the emergence of terrorist organization Boko Haram in Nigeria, which capitalized on the large number of young men who couldn’t find work in Nigeria, and the social unrest leading up to and following the Arab spring in Northern Africa.

President Akufo-Addo went on to outline his vision for the African continent, and for the instrumental role that young people will play in it. To make it happen, he said African countries would need to invest significantly in human capital by following a similar model that spurred economic successes in South Korea, Malaysia, Japan, and Singapore.

But even as organizations like the African Development Bank and governments like Ghana’s support programs and investments to promote youth employment, these steps are threatened by the current pandemic. Many NGOs, international agencies, and governments alike expect funding cuts, and the World Bank now predicts a recession in Sub-Saharan Africa for the first time in 25 years that will cause at least half of all jobs in that region to disappear.

Informal = Excluded

Aside from an existing unemployment problem, young people in the developing world face another vulnerability in the midst of the corona crisis in that most of them are informal workers. There are around 2 billion people in the world who work in the informal economy, many without health care benefits or unemployment assistance. These workers do everything from selling goods at local markets or on the street, to performing agricultural labor, to repairing cars and plumbing. Informal businesses and workers don't pay taxes, and in turn, are often ineligible for government benefits or worker protections. While informal work is already characterized by the United Nations as vulnerable employment, the COVID crisis further imperils these workers, as they may be ineligible for economic stimulus packages and other government assistance programs.

"It has definitely affected most those who are in the informal economy. Informal economy is very much related to the relationship between the employer and the employee. There’s no structured policy, no guidelines. There is no stimulus package for that. There is no support. These are the people most vulnerable to this situation,"

Dr. Malabika Sarker, Professor and Associate Dean, BRAC Univerity James P. Grant School of Public Health

The challenge of how to support informal workers during the economic crisis brought about the pandemic is both unique to and essential for developing countries to keep poverty at bay. 93% of the world’s informal businesses exist in developing countries, meaning successful relief packages in these should look different than packages in wealthier countries. Efforts such as reducing the central bank interest rate and extending tax filing windows won’t help informal businesses. Many of the benefits offered by existing stimulus packages exclude informal workers and people who don’t possess official personal identification. According to the 2018 Global ID4D Dataset, about 1 billion people don’t have an official ID and half of them live in Africa. The result of such policies when offered alone in developing countries is the exclusion of a significant portion of the world population.

Professor Sarker added that the effects of the crisis on informal workers won't end with the pandemic. In the short term, these workers likely won't receive economic aid. But meanwhile, people who are sick or injured but not infected with the virus won't be able to access health care. "When the lockdown is lifted, they’ll be more sick. Going back to work will be problematic for them." In times of "panic mode," she further explained, "even with the resources we do have, we aren't able maximize them because everyone is panicking."

Policy Against Poverty

As governments scramble to support beseiged health care systems and ensure that their most vulnerable citizens have enough to eat, deficiencies in welfare coverage and delivery for informal workers have become glaringly apparent. Governments in developing countries must innovate to find ways to reach their informal workers, and they must do so while operating on immensely smaller budgets.

At least two methods developing country governments could employ to reach their most vulnerable citizens: a ration card system and/or direct cash transfers. However, in order to pursue either option to the fullest extent, policymakers will have to eliminate the identification barrier to access benefits. In doing so, they will face a tradeoff between providing all their citizens coverage during the recession and potentially exposing themselves to fraud. In a "Special Series on Fiscal Policies to Respond to COVID-19", the IMF provided a guide to digital cash transfers, warning of the need for mechanisms to prevent both fraud and corruption in a scenario when KYC policies are temporarily waived.

Amartya Sen, Raghuram Rajan, and Abhijit Banerjee jointly penned an op-ed in The Indian Express in April proposing a ration card system and arguing to accept the potential costs of an economic relief system that doesn’t require an ID. In their proposal, ration cards would be available for any Indian citizen who waits in line to receive one with no strings attached. As for the tradeoff, they write: “The cost of missing many of those who are in dire need vastly exceeds the social cost of letting in some who could perhaps do without it.”

Similarly, the direct cash transfer option would require the alleviation of documentation protocols. Without documentation, many people are unable to access a physical or digital bank account, which is usually needed to receive money from the government. Policymakers could partner with banks and fintechs to at least temporarily offer physical or digital accounts that could receive economic relief. Such an approach brings its own set of challenges, however. While digital transfers might be easiest from a deployment perspective, not all people have access to the internet or the devices required to open a digital account.

There are already several examples of countries taking advantage of digital cash transfer options. Togo has introduced a relief plan in a similar vein. In a program called Novissi, the government offers an unconditional cash transfer for its informal workers that is transferred via a government mobile application. Citizens can access the app and receive benefits worth at least 30% of minimum wage by presenting their voting card. The program is also preferential towards women, with the justification that they are “are more directly involved in nurturing the entire household.” According the program’s website, it had paid out the equivalent of over $8.2 million by the end of April.

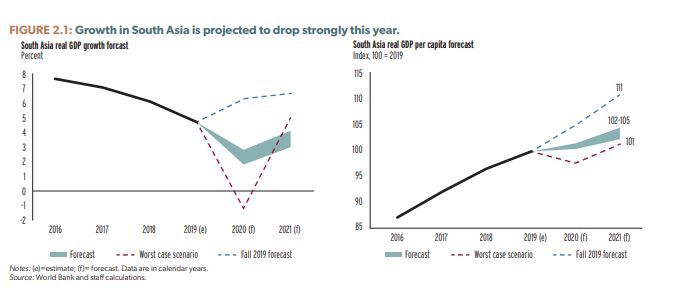

Pakistan is undergoing its largest economic relief program to date through its emergency cash transfer program, launched in early April. With a budget of $900 million, the program will distribute $200 a month to 12 million families for three months, and will employ biometric identification technology to secure the payments. South Asia, regionally, is in the early days of COVID, but some fear that government actions will not suffice to curb the virus's spread in the region's desely packed cities, and economic outlooks for the year run the gauntlet from glum to ghastly (with the poor, again, being disproportionately vulnerable).

Source: World Bank

In Latin America, Peru has successfully deployed relief funds to 50% of Peruvians through an existing interoperable payment switch through an app called Bim. The country recently approved a $26 billion economic stimulus plan that will support poor families via direct cash transfer, as well as allowing early withdrawal of public pensions.

Assist, Invest, Employ

There are other ways policymakers and NGOs can support young people in developing countries during COVID. The African social business consortium The Challenges Group outlined a number of measures this month that would assist during and after the crisis, including training for higher-value jobs, offering cash incentives to small businesses who accept interns or apprentices, and creating incentives for investments in industries that support youth employment in the developing world.

No matter how policymakers choose to craft emergency relief packages in developing countries, they should certainly bear in mind the well-being of their youth populations. The economic health of this age segment is crucial for the futures of their countries and global poverty reduction. Moreover, the challenges faced by young people are representative of the challenges of other vulnerable people in a given society.

If anything, the COVID crisis has brought to light immense inequities that have lingered for decades within individual countries and among the world order. Wealthy countries compete for a dearth of coveted and essential medical supplies, leaving poorer countries and their populations lacking. Poorer countries' futures may hang in the balance if wealthy countries cut back funding for poverty reduction efforts that are more essential now than ever. In country, economic relief efforts for the poor are only as effective as the distribution systems are inclusive. To overcome this crisis, governments must innovate to overcome historical barriers to welfare and accept the short term costs, because the futures of the world’s poorest, and youngest, are at stake.

Image courtesy of Sergio Souza

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

East Asia Reopening: A Model To Follow?

Without A Trace: The Risks And Rewards Of Privacy Post-COVID