Big Tech in Financial Services: A New Regulatory Paradigm

~11 min read

The digital age began in the 1990s with the Internet’s “information superhighway.” For the first time in history, the modalities of information, communication and commerce were a mere click away. Today, a single click no longer embodies a gateway to a panoply of websites run by small-time Internet entrepreneurs. For the small-time entrepreneur, the power of one click is now embodied by a one-click buy processed by Amazon Pay to the individual seller whose business is funded by Amazon Lending on the only viable e-commerce platform for such sellers in many markets — Amazon.

The previously diffuse, independent ecosystem of digital offerings is now significantly shaped and structured under the closed-loop ecosystems of big techs. As Big Techs penetrate deeper into facets of financial services, the novel and wide-ranging business structures of these big techs invite profound issues in areas of data privacy, competition and financial stability that can’t be solved by the antitrust regimes of old. Who regulates such tech behemoths armed with unparalleled data access spanning financial, commercial and communication industries — and how? The penetration into financial services by ecommerce giants like Amazon and social media titans like Facebook presents a complex, multi-faceted challenge for authorities that demands a rethinking of regulating industry itself.

The Rich Get Richer

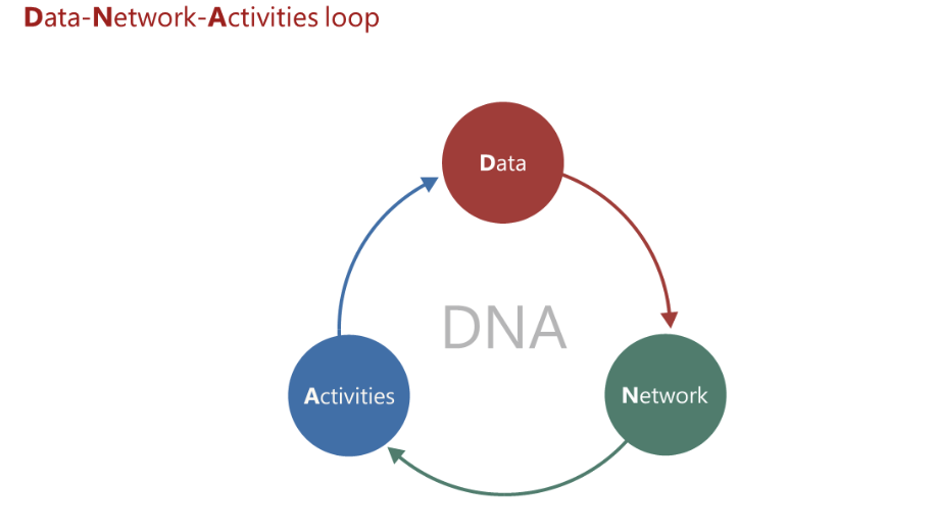

Financial services still comprise a small share of total revenue generated by big techs, about 11% according to latest estimates, yet their impact on external and internal ecosystems is less easily defined. As framed by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), big techs’ business models are defined by three features unique to the digital economy: data analytics, network externalities and interwoven activities, or “DNA.” In a big tech platform, commercial activity increases in value as the number of users increase, which drives greater adoption — which leads to greater data to mine, fueling the advanced data analytics powering these platforms. This enhances existing services and attracts further users, creating a feedback loop that facilitates rapid scaling and market power. The “DNA feedback loop” is premised on different sources of data to analyze — an e-commerce platform collects data from vendors and combines it with financial and consumer information, while big techs focusing on social media have data on individuals, their preferences, and their network of connections. The more encompassing the data sets are, spanning various modes of commerce and communication, the more potent its monetization plays are — whether it be paid advertisements for Facebook or commercial activity on Amazon.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

The entry into financial services by big techs thus aren’t simply ventures to utilize their arsenal of data in other sectors to offer superior financial services, which it certainly is capable of — it also adds invaluable financial data to the array of data gleaned elsewhere within their ecosystems. To a great extent, this is why big techs would even enter financial services, a highly regulated sector that is less profitable than big techs’ core technology businesses. Though their presence in financial services only grows further, big techs have principally targeted the areas that would be the most profitable from data- and revenue-generating standpoints — and which require the least regulatory restrictions and oversight.

“I don’t think big techs are interested in becoming banks. The return on capital in the banking industry is much lower than the one in tech. It’s not in their DNA. They are going to act as a bank as long as it interests its core business: as long as they can get some data, some profits, as long as they can straddle the ecosystem — I always stress this ecosystem mindset that big tech has.”

Nicola Bilotta, Researcher, Instituto Affari Internazionali, and author of “The Rise of Tech Giants: A Game Changer in Global Finance”

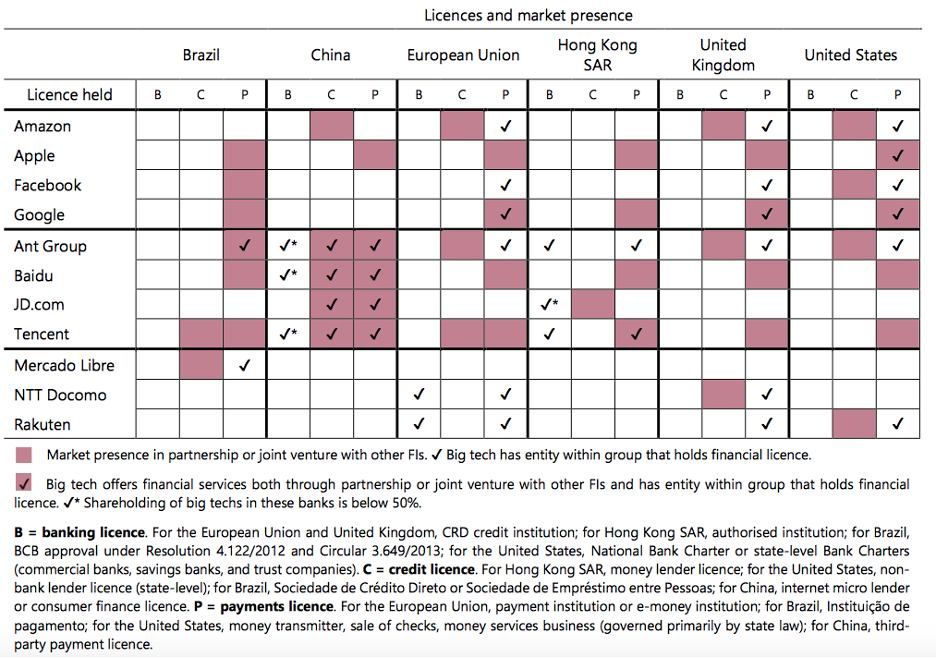

With this approach in mind, payments have emerged as the leading area of financial services that big techs penetrate. Strengthening their own self-contained ecosystems, payments offer big techs valuable data they previously didn’t have access to while typically only requiring an e-money license to operate. Google Maps can discern if a person decided to go to a bike store, but only through Google Pay can the company understand if and what they purchased. Regulations regarding financial activities become far more stringent when deposit-holding activities are incorporated. Servicing payments processing, however, enables big techs to understand crucial consumer activity while banks and credit card companies (largely) do the critical backend work on a systemic level.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Credit is also an area where many big techs have ventured into. In this case, the superior consumer data they possess in areas such as payments, ecommerce and social media can better inform credit origination decisions and provide lending to the otherwise thin-file unbanked. The access and network advantages that big techs possess enable them to establish a greater financial services presence in emerging markets, which often have less robust regulations to boot.

“Facebook has the unique situation that there are more Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp accounts in the world than there are bank accounts. So Facebook is going to very much play the role of being the bank for the unbanked, meaning your bank on your smartphone. That is why they are getting e-money licenses to allow you to make payments and overall microfinancing, etc. — they are going for the role of being the bank for especially rural areas.”

Pinar Ozcan, Professor of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Saïd Business School

Though offering positive benefits in areas such as financial inclusion, the ecosystem-oriented ambitions that big techs have in financial services limit the offerings for previously excluded populations to basic services like payments and credit. Cross-industrial integration of data and offerings can also enable such companies to leverage unmatched authority and pressure on individuals. If a seller falls late on payments to its Amazon Lending balance, for instance, Amazon can choose to block this seller from its ecommerce platform — all but a death knell in certain markets.

By also serving as the intermediary for credit origination in partnering with banks, big techs can escape some of the capital requirements lenders would typically be beholden to. The potential dangers of this grey area in regulations have been exemplified most clearly in China, where big techs have already taken a systemic importance in financial services not seen elsewhere. Before the recent regulatory crackdown, Chinese users of Alipay owed $271 billion in debt after Alipay originated loans backed by commercial banks without the typical due diligence a creditor would typically initiate.

Operating as a financial entity without the same requirements as a financial services-centered business enabled Alibaba’s subsidiaries to operate in ways a financial service provider normally couldn’t. In the case of MYBank, the big tech’s “digital bank,” Ant Financial would operate in the credit market through buying money in the market rather than having sufficient deposits to finance their loans, with a subsequent ratio between deposits and loans lower than the regulatory ratio demanded by the central bank.

Granular, alternative data is the critical component to offering lending to those otherwise financially excluded — but consolidation of consumer data can just as easily be weaponized. Although more data produces better lending decisions, it can also provide companies the tools to measure the largest amount borrowers will pay back — while utilizing their interwoven activities to compel repayment. Though other digital creditors may technically be available, the same traditional effects of monopolization may nonetheless permeate.

Involving themselves in financial services without fulfilling typical prudential requirements, as Nicola Bilotta, researcher at the Instituto Affari Internazionali, puts it, “they are ‘not doing finance’ — but they are doing it.”

Too Big to Regulate?

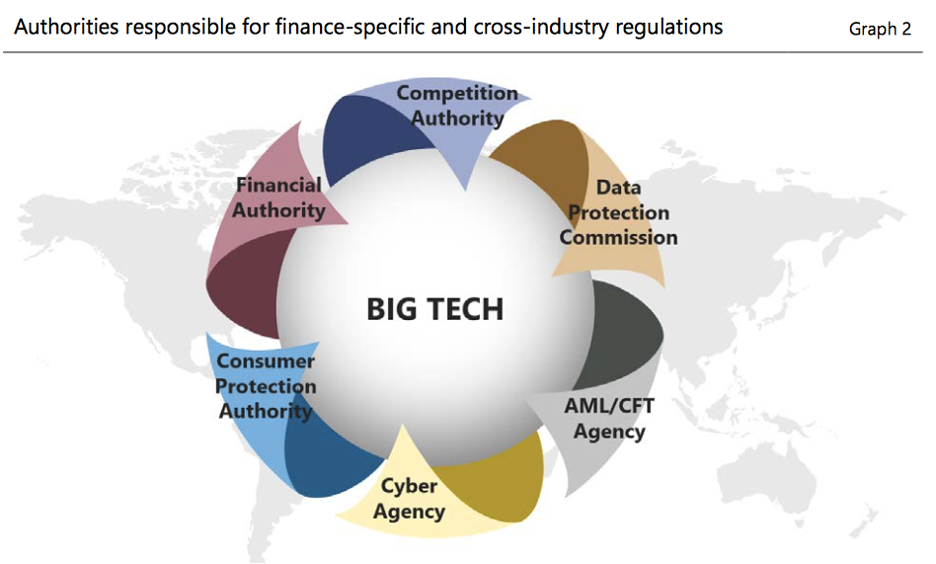

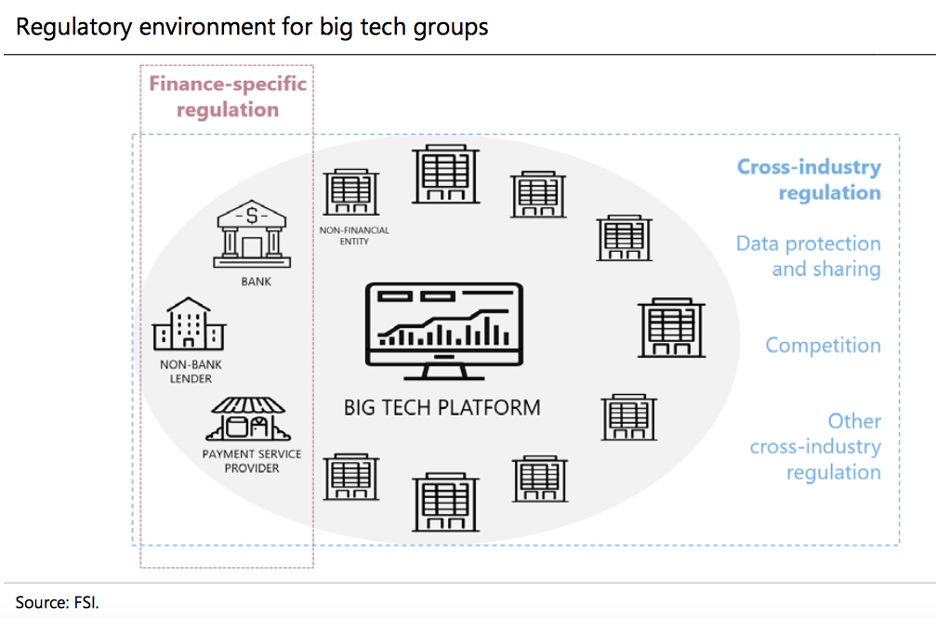

Big techs have thrived operating in this regulatory grey area of cross-industrial finance and commerce driven by multi-sourced data. The simultaneous harvesting and utilization of cross-industry data challenge how traditional regulatory regimes function. Regulators are concerned about big techs in three areas in particular: financial stability, fair competition, and data governance. The interwoven activities of Big Techs encompass several regulatory verticals that operate separately:

Source: Bank for International Settlements

How regulatory regimes have been traditionally constructed is therefore insufficient in addressing the systemic risks that big techs in financial services pose. Typically, financial regulations have taken an activity-based approach — in which regulations are applied to any entity that engages in certain regulated activities in the spirit of “same activity, same risk” — in theory levelling the playing field among all entities engaging in the same activities. But while activities between a big tech creditor and a bank creditor may look the same, the data and analytics underlying such activities are wholly different. Such regulatory approaches provide too narrow of a regulatory regime to consider the differences and curtail regulatory arbitrage, which the unique data flows and cross-border activities of big techs invite.

When considering potential systemic risks, the cross-sectional nature of big techs’ involvement in financial services are not adequately addressed in this traditional regime. The dominance in cloud services by big tech providers like Amazon Web Services — which owns a 32% share of the global cloud infrastructure market — underscores the systemic importance such providers have when it comes to data governance. One of the major trends Bilotta identifies regarding big tech in financial services is the preponderance of partnerships between traditional financial institutions and big techs’ data analytics teams. Though possessing a wealth of data on their own, and with often significant user bases in their own right, banks and other institutions rely on big techs’ data analytics to keep up with the innovations springing forth.

“In highly regulated markets like finance and healthcare, big tech won’t necessarily be very visible in the market, but that doesn’t mean they won’t be powerful. They would never be a hospital; they would never be a school. But they will be handling the data for most companies and then providing the prediction services that these institutions desperately need in order to be more effective.”

Pinar Ozcan, Professor of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Saïd Business School

Big techs’ data regimes and related commercial activities thus challenges traditional notions of ensuring fair competition and financial stability. The systemic risk was most obviously exhibited in the recent six-hour shutdown of the services that Facebook owns, including WhatsApp and Instagram — ostensibly social media channels, the shutdown cost businesses hundreds of millions dollars, impacting major ecommerce providers and local merchants alike. The traditional divisions of finance, commerce and media sectors have been all but erased among these platforms, with data driving innovation and market dominance, yet circumventing traditional regulatory approaches.

“We need to completely rethink how we regulate these entities. The antitrust paradigm is mostly based on the 1890 Sherman [Antitrust] Act: you are too huge, it is too risky, you can actually increase prices for customers, so I need to punish you and you need to break up. [But] the digital economy works differently. How you compete is completely different. Now you compete on networks, on data accumulation — so you need different rules.”

Nicola Bilotta, Researcher, Instituto Affari Internazionali, and author of “The Rise of Tech Giants: A Game Changer in Global Finance”

Rethinking Regulations to Their Core

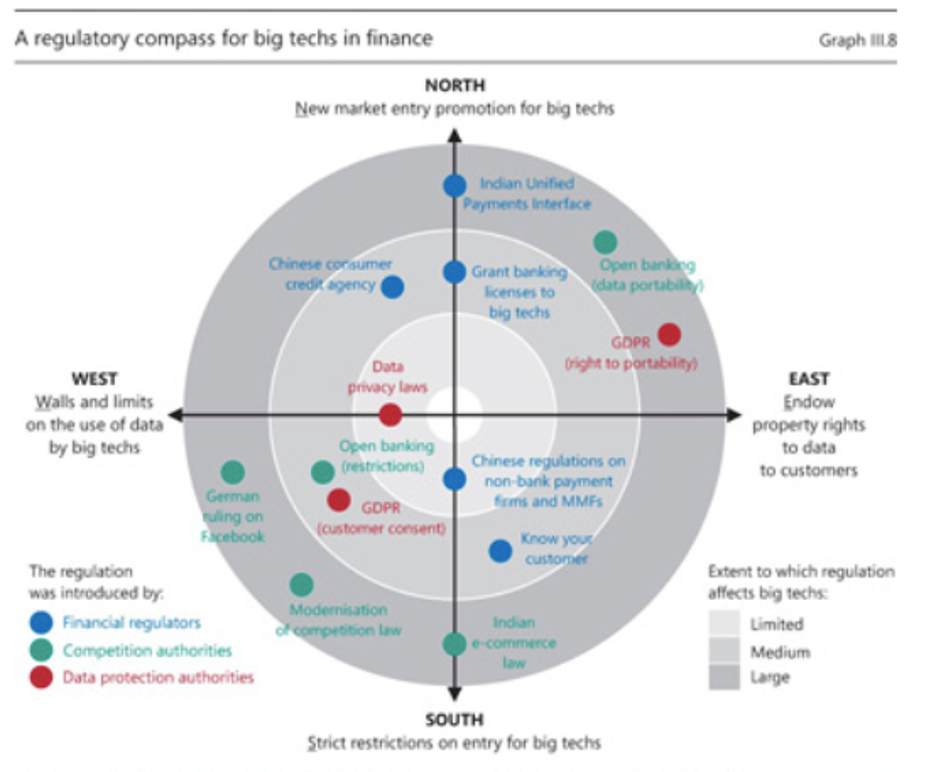

The need for regulatory reform entertains competing visions for how to harness the positive potential impact big techs can have in areas such as financial inclusion while reining their market dominance, preserving data privacy and governance and safeguarding against systemic risks. As Mondato recently discussed, how open banking is applied can determine whether big techs’ data advantages multiply or diminish. The EU’s GDPR, for example, mandates data sharing among financial activities but shields big techs from sharing their non-financial data. In Australia, by contrast, open banking mandates total reciprocity in data sharing. However, as Ozcan notes, reciprocity by itself doesn’t overcome the gap in application; banks already have considerable shortcomings performing data analytics within their own ecosystem, let alone employing AI to integrate and analyze non-financial data.

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Shifting away from the strictly activity-based regulatory regimes of the past, experts and authorities are eyeing a mix of activity-based and entity-based regulations to oversee big techs. In contrast to activity-based regulations, which rely more on enforcement of clearly defined rules, entity-based regulations would create regulatory regimes comprehensively and continuously supervising the activities of big techs at the entity level, likely with governance, prudential and conduct requirements.

The emergence of entity-based regulations is emerging particularly in China, the E.U., and the U.S. In China, which with much fanfare took swift actions to corral the activities of its resident big techs, the most major action, among other changes, is requiring all entities holding two or more types of financial institutions to be structured and licensed as financial holding companies. This mandates big techs to reorganize their financial businesses while entailing supervision of big techs though all their financial subsidiaries and how their different businesses interact in areas of data and capital. In the E.U., the proposed Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act seek to establish extensive requirements for very large online platforms, or “gatekeepers,” defining them according to geographical presence, total revenues, market capitalization, and the number of active users. In the U.S., congressional committees have proposed similar initiatives.

Complementing existing competition laws, the goal of these novel regulatory approaches is to prevent the propagation of unfair competitive practices and data abuse ex-ante rather than ex-post — commencing proactive rather than reactive regimes of old, while creating novel regulatory frameworks that incorporate the interdisciplinary nature of big tech operations. As Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland president and CEO Loretta Mester said in a November 2020 speech, big techs require “a more holistic blending of financial regulation, antitrust policy, and data privacy regulation, with cooperation across different regulators and structures created to allow for systemic coordination.”

Yet as more experts and authorities coalesce around such novel regimes, most agree that such efforts may ultimately be futile without multilateral coordination. Otherwise, big techs are ripe for regulatory arbitrage. In Germany, for example, the competition authority prohibited social networks from combining its user data with those it collects from affiliated websites and applications — a direct blow to big techs’ powerful DNA feedback loop. But such efforts are impossible to regulate cross-border, with big tech operations largely left undisturbed on a global scale. As big techs’ influence in the financial sector grows — and especially with the possible advent of big tech-originated stablecoins, considering their potential to create closed-loop private monetary systems — greater multilateral coordination is bound to come, elevating the importance of international organizations like the Financial Stability Board in overseeing cross-border, cross-industry entities. But innovation always remains one step ahead of regulations that will take years to fall into place.

No two big techs are the same in their market emphasis and business model, demanding continuous supervision and adaptation of regulatory regimes equipped to handle big techs’ unprecedented data blending of finance, commerce and communication — a tall task for regimes borne of analog eras. Antitrust “break ‘em up” approaches of old may be entertained in some political circles, but the impact such efforts may have on novel business models remains a fearful unknown among most experts.

Rather, the domination of the digital economy by big techs requires the “systemically important” designation traditionally accorded to financial institutions to expand to more holistic definitions. An agile, proactive regulatory regime such fundamental changes require would signal a historical reformulation of what regulating finance and commerce entails Yet the traditional separation of finance and commerce most famously stipulated by the U.S.’s 1933 Glass-Steagall Act has already vanished in our globalized, data-driven, digital world. The challenge now posed to regulators is how to operate in a blurred commercial world where everything is connected, data interwoven with data. Whether the vast powers of big techs spanning industries can be harnessed is an open question — yet one that will impact all contours of digital society itself.

Image courtesy of Gina Domenique

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Can Digitization Reduce Mass Migration From The Northern Triangle?

From Mobile Money Powerhouse to Super App: The Case of M-Pesa