Can Digital Monitoring Unlock Climate Finance?

~9 min read

Last year, Mondato partnered with the GSMA to map the landscape of innovative finance instruments targeting improved delivery of basic services to low-income populations in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. The research aimed to unpack the “digital layer” sandwiched between funders and beneficiaries, enabling novel investments across the spectrum of commercial and “impact” instruments. This week’s Insight grounds the report’s framework in the uniquely instructive health facility electrification case study to highlight what role digital technologies play in shaping innovative finance for the business of health.

Digital Impact Capital

How have successive waves of digitization transformed the way outcomes are tracked in the provision of basic services in low-income countries? This is the question the GSMA’s Digital Utilities team asked Mondato to tackle in 2023. The research, focusing on digital technologies that enable innovative finance for energy, water, sanitation, mobility, agriculture and nature-based service solution providers across Sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, resulted in one of the first landscape analyses of the digital finance - utility service intersection writ-large, an accompanying Innovator Guide and two webinars profiling selected innovative finance instruments.

According to George Kibalua Bauer, director of the GSMA’s Digital Utilities program, this work sought to assess various innovative financing solutions, hoping to better close financing gaps for essential utility services.

“The growing adoption of technologies like digital payments, digital platforms, IoT-enabled remote monitoring, and AI has not only transformed how SMEs, start-ups, and social enterprises across LMICs operate, but has also transformed how they can access different forms of financing. Digital technologies are opening the door to new financing models, and improving the effectiveness of more established models.”

George Kibala Bauer, Director, Digital Utilities, GSMA

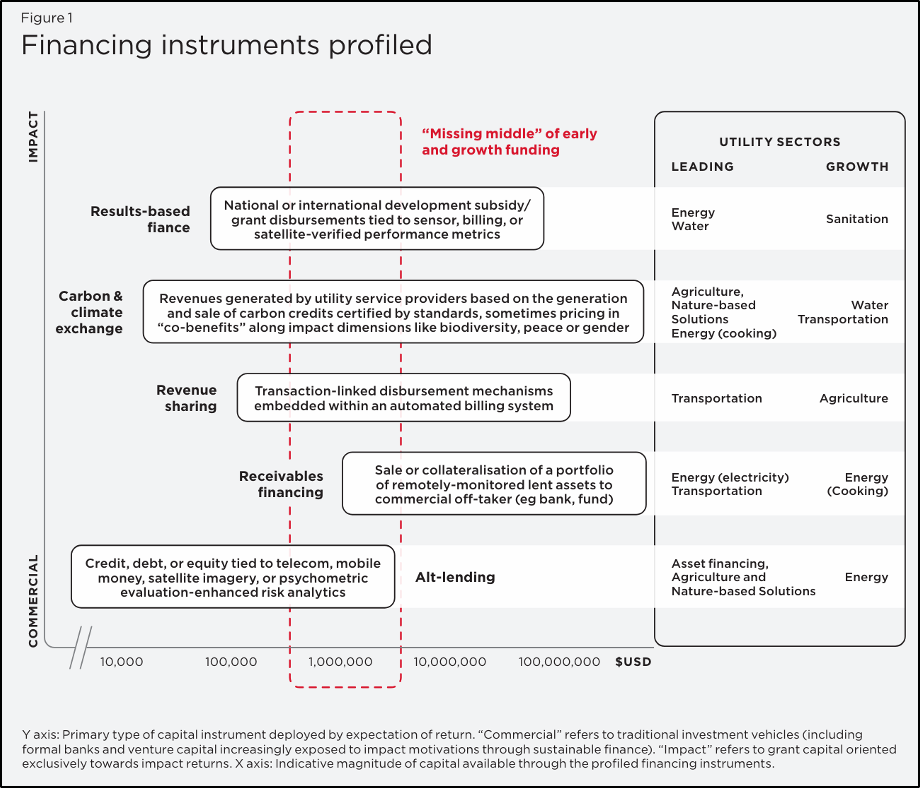

At the inception of this work was the development of a conceptual framework to organize the complex flows of information and funds between senders and recipients. The framework builds on the study of global value chains, enabling a mapping of flows and interactions between the ‘upstream’ — in our case, the sources of innovative finance — and the ‘downstream’ — the utility and utility-adjacent firms and their customers — isolating distinct features of ‘innovation’ each step along the way. The report highlights five innovative financial instruments from the landscape, selected for representativity across the flavors of purely commercial kinds of cash (equity and debt) versus impact-oriented capital (grant, gifts and subsidies) intended to achieve social outcomes (with proof). Across the categories of financial instruments employed, the “missing middle” of early and growth funding persist, nonetheless.

Instruments profiled across the commercial-social impact return spectrum, highlighting the 1-5 million dollar range where the landscape review and interviews emphasized a particular deficiency in the existing financing ecosystem for basic utility services.

Source: GSMA (2024)

Cash Flow for Clinic Power

The health facility electrification nexus offers a critical insight into how sector-specific funding dynamics influence the kinds of cash available for enterprises invested in tackling social problems.

Energy services, on the one hand, are the most mature among traditional utility sectors, by age and investment activity; indeed, since the emergence of the pay-as-you-go (PAYG) solar power lighting market around 2010, the supply-and-demand for solar power, cell phones and mobile money systems have paved the way for frontier digital innovators to bring power to 25-30 million people worldwide between 2015-2020. Today, individual energy service companies like d.Light and BBOXX are increasingly securing commercial working capital loans to scale their asset finance-heavy model to the tune of more than $230 million and are among the digital finance ecosystem’s most important players.

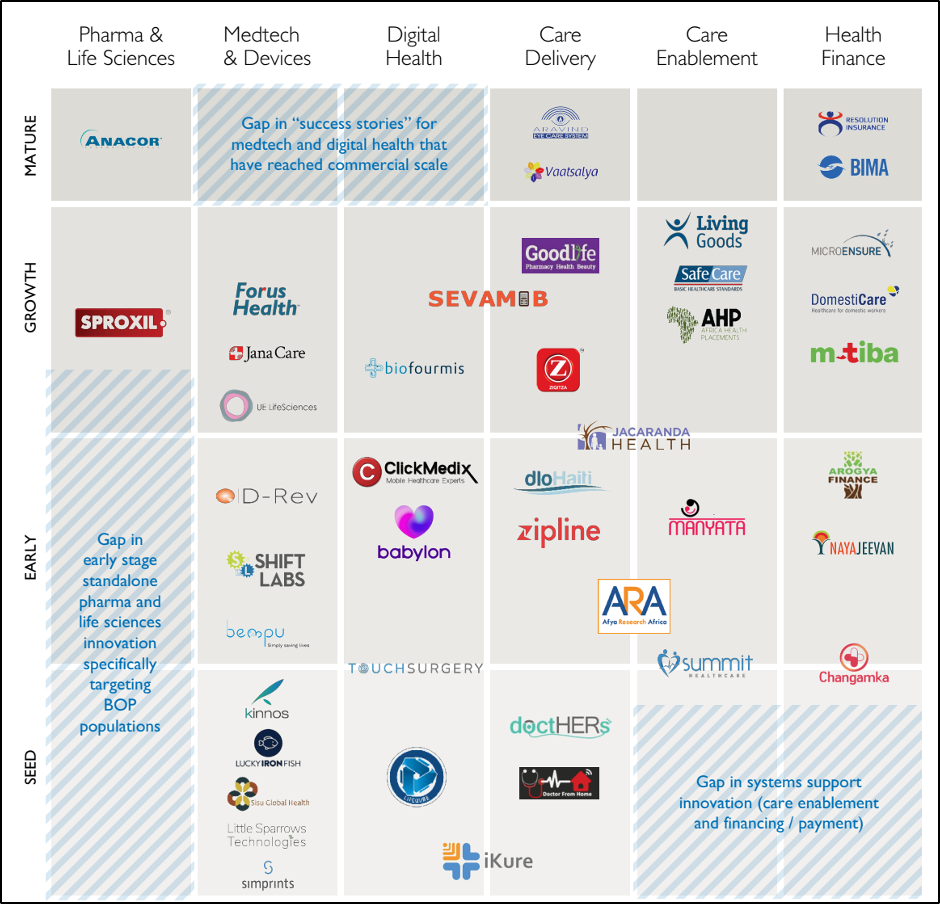

The health sector, for its part, operates in a completely different financial universe: one where development finance institutions (DFIs), philanthropists and government priorities constitute the main sources of funding for the pharmaceutical, diagnostics, stock management system, electronic records system and myriad other healthcare functions. The dominance, in particular, of a small group of influential funders in the health space, along with international coordination efforts around public health, have seeded a growing but fragmented ecosystem of small- to medium-sized tech companies tackling the structural health system gaps exposed by the pandemic.

M-Tiba is one of a few HealthTechs who confront head-on the elephant in the room when it comes to financing healthcare: what is the payment channel for the service? Their solution, built for the Kenyan market, acts as a digital intermediary between patients, insurers and donors, and it is accessible over the country’s vibrant USSD-enabled payment system. Elephant Healthcare, focusing on patient management and stock inventory financing in Nigeria, is another such promising solution provider that has raised over $10 million in growth capital. Their model hinges on partnering with local governments for the rollout of app and QR code-based patient intake, records and payment management systems.

Despite the strength of the off-grid energy market and the volumes of public and private investor attention into HealthTech, there remains relatively little growth-oriented, capital-fueled entities dedicated to solving health facility electrification specifically. Despite the fact that unreliable electricity leads to the loss of nearly half the vaccine supply and the failure of 70 percent of medical equipment in Africa, the past decade has seen an average yearly spend in the sector of around $30 million per year on facility electrification, leaving an estimated investment gap of $2.5 billion.

Source: USAID 2022

Source: USAID 2022

Remote Control, Close-Up Impact

This health-power gap found a champion in the American government’s private-public Health Facility and Telecommunications Alliance (HETA) initiative, a USAID agency-led private-public initiative that takes market-based approaches to solve development challenges. Announced mid-pandemic to tackle the health-power gap in Africa, HETA deployed a set of results-based co-financing instruments: pay-for-performance impact grants, chunked out to companies able to prove their “development bang per buck.” The difference this time from previous waves of hardware-heavy approaches? Call it “the corona effect:” everything has gone remote.

OffGridBox is a recent HETA partner. It designs, deploys and operates what could be described as a “mini-multi-utility model.” Initially founded to use solar power for providing clean water and connectivity to remote communities, COVID brusquely pushed the company into powering health facilities to counter gaps in vaccine cold chains. They partnered with UC Berkeley researchers field-testing remote monitoring systems in North Kivu Province in eastern DRC, where COVID, ebola, unpredictable volcano explosions and decades of cyclical geopolitical upheaval — on top of catastrophically low electrification rates — were crippling the health system.

Together with researchers, local health authorities and community organizations, the consortium formulated a sample of 25 provincially-representative facilities to monitor through outlet-level sensor installations and WhatsApp-based interviews. After a year of monitoring, six facilities in the region with the worst power quality were fast-tracked for a humanitarian energy technology intervention, providing a solar-plus-equipment package on a lease-to-own basis supported by HETA and experimentally monitored by third party verification specialists like nLine and A2EI.

Though remote monitoring is not new, digital monitoring, reporting and verification efforts worldwide stand to benefit from the maturation of mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs), whose off-the-shelf eSIM offerings make it increasingly possible to turn any ‘dumb’ sensor into a live-stream.

While the utility of live-tracking installations is clearly superior to the “dump-and-disappear” strategy that characterized previous waves of health electrification efforts, it is also clear in the Big Data era that more data by itself may be a necessary but not sufficient solution.

“To this day, not everyone yet gets the value of monitoring, nor understands how to price it. Rather than look at the cost of a single sensor, for example, or a single platform, you really need to look at the value of the signals you are seeking and producing in aggregate, and that requires a system-wide perspective that is challenging to develop.”

Noah Klugman, CEO of nLine Inc.

Despite massively reduced costs and complexities of managing dedicated remote monitoring systems over the last few years, it can still be hard and expensive for non-specialists to develop a responsive monitoring strategy, which ultimately requires people to monitor, interpret and act on huge amounts of constantly updating signals. And while artificial intelligence promises to shake up how verification and auditing gets done, results-based finance (RBF) tends to be structurally fixed in time or value, making it best suited for small-scale pilots. In light of these limitations and criticisms, climate finance, and more specifically Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCMs), offers a compelling solution for taking over where RBF leaves off.

Climate Commerce for Clean Energy

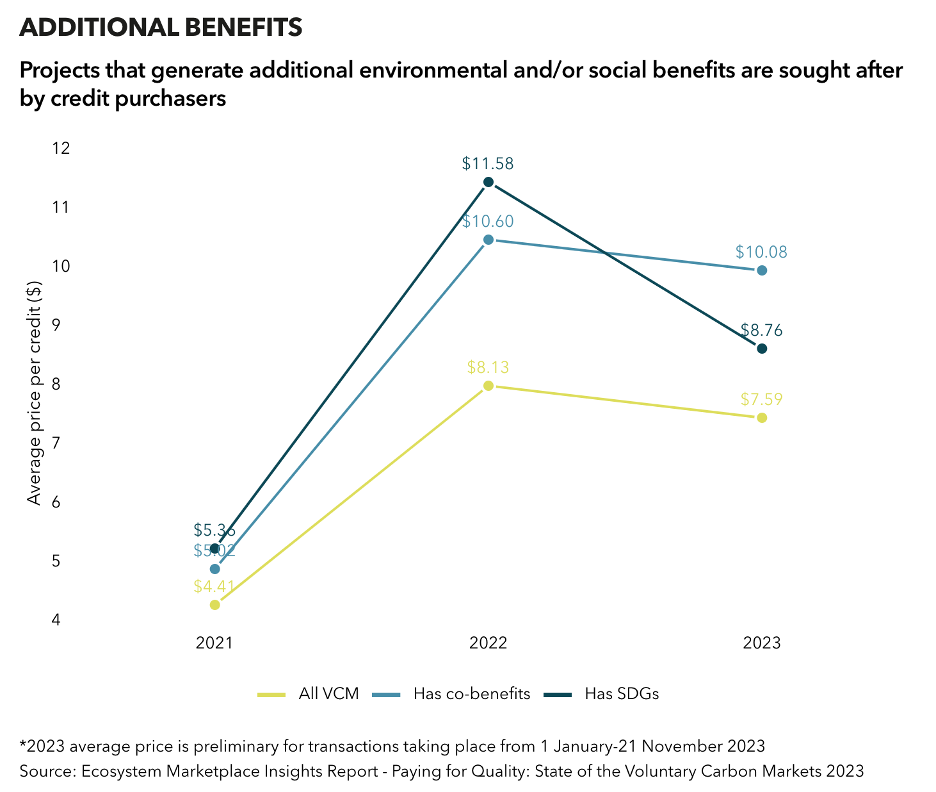

For companies able to capture the right proof of environmental impact, VCMs could well represent the bridge from chasing grants to sustainable finance. While climate finance is a broad term encompassing financial resources mobilized for the specific purpose of achieving social and environmental adaptation and mitigation targets, VCMs are unregulated exchanges where “emissions equivalent” credits are generated based on verified environmental impact and sold to companies seeking to offset their footprint. Globally, VCMs grew at a compound annual rate of over 30% from 2016 to 2021, based on carbon credit retirements, reaching a market valuation approaching $2 billion today and expected to grow to $50 billion by 2030.

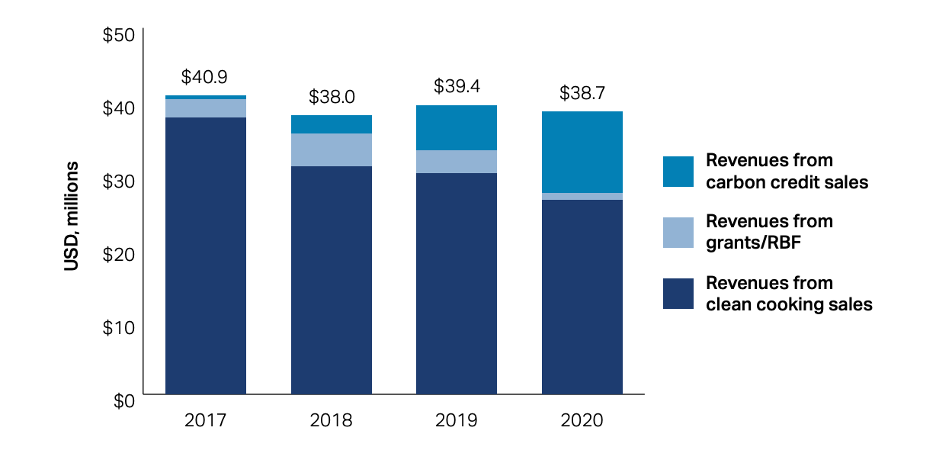

Digital leaders are wasting no time tapping into the early slices of this pie. ATEC, for example, is an on- and off-grid energy technology company offering electric induction stoves on a PAYG basis. An early adopter of PAYG technology, they are among those demonstrating the viability of the ‘climate finance for clean energy’ funding stream.

Source: New Private Markets (2024)

Source: New Private Markets (2024)

Companies like ATEC and ecosystem supporters like A2EI are bullish on the demand — and the price per ton, reportedly varying between $12-35/ton — for such kinds of “DMRV” credits growing significantly, driven by corporate needs as much as, if not more than, for developmental goals.

Stefan Zelazny, of the Access to Energy Institute, says they developed their Prospect platform in response to demand for impact verification along social and environmental dimensions.

“We’ve made enormous progress with our pilot partners in demonstrating attractive results and viability for such finance, particularly given the continuing growth in voluntary carbon market activity projected in Africa. But we are still facing challenges in connecting the ecosystem around the common data collection methodologies and standards that can meet the volumes desired.”

Stefan Zelazny, Managing Director, Access to Energy Institute

Source: GSMA 2024

Source: GSMA 2024

Banking on Digital

Reducing the costs and complexities associated with tracking specific outcomes tied to climate verification metrics, like tons of greenhouse gas avoided or displaced, is one of the critical recommendations of a rapidly growing coalition of health facility electrification champions following the pandemic.

What innovations in digital monitoring and reporting technologies might raise the tide of climate finance to help float the capital commensurate to the challenge? The Task Force on Voluntary Carbon Markets offers some clues, highlighting in particular distributed-ledger technologies, satellite imaging and digital sensors.

But what many of today’s HealthTech companies have in common is that they focus on just one or two vital aspects of a hospital’s functioning, not the whole thing — even if that excludes the basics. Given the fragmented nature of health finance and delivery in Africa, tighter harmonization of indicators underlying performance-tied grants and exchange-oriented voluntary/compliance markets could go a long way towards maximizing data-driven partnerships

At the same time, as with any solution integrating transactional systems, AML/ KYC requirements will inevitably emerge as an obstacle to scale on the commercial end. Thus, a company that aims to tackle the health facility electrification challenge may well find itself in the business of building the financial infrastructure to make money move in difficult places; it certainly wouldn’t be the first time an African startup winds up unexpectedly doing FinTech.

Without the stable base of electricity upon which digital health is powered, the existing crop of HealthTech companies will remain ill-prepared to scale across the geographies where they are needed most. A new way of empowering health through technology may subsequently be necessary: a facility-focused approach that looks holistically at what is most needed locally and pairs it with the best-in-class solutions. Digital monitoring technologies offer the possibility that this can be done efficiently at scale, as well as a window into a potential future where real-world impact data — digitally audited, verified and converted to cash — helps finance life-support for the world’s climate-vulnerable.

Image courtesy of Ben White

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Argentina: Can Bank-Driven Wallets Compete With Big Tech Platforms?

CBDCs: The Answer To Cross-Border Inefficiencies?