Payments Banks: Nigeria Takes A Page From India

~9 min read

Since it was rebased in 2014, Nigeria’s economy overtook South Africa’s as the largest in Africa. Despite relying almost entirely on oil exports for foreign exchange, Nigeria’s economy is actually fairly diversified, with services contributing over half of GDP. Yet despite a relatively advanced banking sector (and a red-hot fintech ecosystem supported by a sizable venture capital system), financial exclusion remains persistently and disproportionately high.

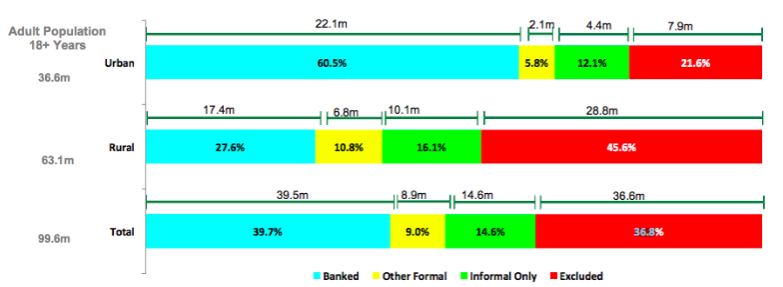

Last year, EFInA put the tally of ‘eligible Nigerian adults’ with access to financial services at 63.2 percent, leaving nearly one in five Nigerians to be reached before the end of the year to hit the commitments the country solidified in 2012. Recognizing the limitations of its bank-led model, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) decided to up the ante while shifting gears, raising its target for financial inclusion to 95 percent by 2024 and releasing a new class of financial licenses specifically targeting financial inclusion called Payment Services Bank (PSB) licenses.

PSBs: Banking (Un)Leashed?

A PSB license gives awardees explicit permission to perform some familiar - and basic - functionalities of a digital finance and commerce (DFC) ecosystem. Principal among them are cash-in and cash-out functions (CICO), person-to-person payments (P2P, which includes domestic remittances) and person-to-merchant transactions (P2B, which encompasses paying for goods and services to merchants as well as paying bills). Of course, all of these functionalities and more are already offered by a deep bench of traditional and fintech players in Nigeria. PSB licenses, however, offer a hesitant but definitive step in extending the range of players permitted to offer such services even further, to players like courier services (think DHL or UPS), formalized chains with existing rural physical footprints like supermarket chains or downstream petroleum players - and, critically, telecommunication companies.

To many, the creation of a new class of licenses specifically geared towards deposits and payments is reminiscent of the Indian tiered model, also promulgated by central banking agencies in an explicit bid to universalize formal account ownership. Launched in 2015, the Indian experience with PSBs are underwhelming by a number of metrics. The churn of Indian companies who applied for, then dropped, their bid for a PSB license has been extremely high (from nearly 41 initial applicants to four active licensees today), and the survivors have faced a number of high-profile tiffs resulting in players being fined rather than unleashed.

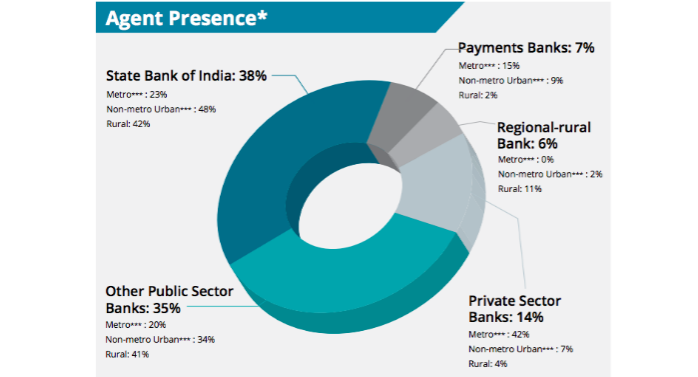

As of the end of 2018, payments banks represented less than 10 percent market share of agent presence, and only 2 percent share in rural India, while profitability for licensees has remained elusive for most (with the notable exception of PayTM, who has managed to post a $2.7 million profit after two years of PSB operations).

To be fair, the Indian PSB experience has been marked by an extremely hands-on government whose centralized pushes for financial inclusion rendered moot many of the opportunities and promises accompanying PSB prospects. Nevertheless, given the mixed results of the tiered banking model in India, Nigerians are well within their rights to assess the expected impacts of CBN’s policy direction with skeptical optimism.

Indian Lessons, Nigerian Challenges

For all the theoretical similarities between PSBs in India and Nigeria, the context in the latter holds significant differences. Perhaps the biggest difference in Nigeria is the fact that Indian government-tied entities like the Reserve Bank of India have taken a much more active role in promoting formal financial inclusion, with initiatives like Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, Aadhar and Unified Payments Interface all significantly contributing to achieving formal account coverage for a reported 99 percent+ of households - garnering the government-led financial inclusion campaign a Guinness Book record for most bank accounts opened in a week.

India’s financial inclusion drive has also been spurred by its demonetization, a systemic shift in the financial system that spurred digital finance adoption in ways reminiscent of how the 2007/8 financial crisis helped pave the success for M-Pesa in Kenya.

At the same time, there are some definite lessons the Central Bank of Nigeria could learn in order to avoid some of the mistakes of the Indian experience. Of the few players who did stick with a PSB license, all have struggled with compliance with sometimes ill-defined regulations drawn around procedures ostensibly designed to preserve the integrity of the traditional financial system. Last year, Fino ran afoul of regulations around how much money account holders were allowed to keep in accounts, and PayTM and Airtel were both fined for violating KYC / onboarding processes mandated by the Reserve Bank of India. Nigeria’s Central Bank would thus do well to go to extreme lengths to provide an abundance of clarity to PSB applicants on rules of the game, as well as to take pains to make compliance as transparent and simple as possible.

The interest rates PSBs are allowed to offer to customers, for example, is notably left open to discussion in Nigeria - a stark departure from the Indian model where deposit interest rates are fixed by the government. Given that PSBs must hold at least 75 percent of their deposit liabilities in Nigerian treasury bills and other short-term federal government debt instruments, clarity on partnership arrangements with third-party providers that can provide additional revenue streams are critical for PSB aspirants to gauge their potential for profit and scale.

For Nigeria’s PSB scheme to make a significant dent in its renewed financial inclusion targets, then, it is back to the fundamentals. To succeed, PSBs will need to convince unbanked Nigerians to open accounts in droves - and the use-cases that will drive this uptake will inevitably differ by demographic. For the urban unbanked, this will mean delivering a better user experience or more attractive terms than traditional retail banking accounts, which now almost universally offer mobile banking apps and increasingly popular, USSD-enabled transacting. Beating traditional banks - and pure payment fintechs like FlutterWave and PayStack for this demographic may prove difficult for PSBs. Without the ability to generate revenues from lending activities (prohibited as part of the PSB license), they may struggle to turn a profit while competing on transaction fees.

For rural customers, on the other hand, margins are already quite low and the investments in agent networks, cash management, logistics and security are weighty. For agency-focused mobile money operators like FirstMonie and Paga who have built a physical footprint across the country and invested in consumer education, PSBs may thus represent a threat as direct competitors.

Telcos: The Game Changer

As noted earlier, the functionalities offered by PSBs are not new - the biggest difference lies in who is allowed to offer them. In this respect, the arrival of the telcos onto the payments scene is perhaps the awaited game changer offered by the new licensing regime. Hitherto prohibited from using their extensive airtime distribution networks as stores of fungible monetary value, telcos in Nigeria are for the first time being given the green light to get into the action. MTN, in particular, is the telco to watch, with 56 million mobile customers in Nigeria, a significant chunk of whom are in the rural milieus targeted by the Nigerian financial inclusion focus that has in large part spawned PSB regulations.

Unsurprisingly, telcos are uniquely well-suited to drive the digital finance market. Not only is telco bread and butter a low-margin, high-volume business, but they are already sufficiently capitalized to undertake whatever agent network expansions may be necessary on top of their existing networks. MTN, for example, as Nigeria’s second largest stock on the stock exchange by market value - with over 50 million Nigerian subscriber accounts (of those, MTN is the sole connectivity provider for 20 million) and 4,000 corporate branches servicing over 50,000 ATMs and POS devices - should certainly worry traditional deposit banks’ retail department as a potential competitor. Airtel, MTN’s nearest competitor in Nigeria, also benefits from experience with the tiered banking system from its operations in India, while Nigerian home-grown competitors Glo and 9 Mobile have also been showing prominent growth.

Nor is there lack of incentive for these players; as Safaricom in Kenya (already the most profitable company in East Africa) prepares for M-Pesa to account for more than half of its revenue in the next few years, it is looking to drive further growth from more advanced digital finance revenue streams like e-commerce and agriculture. This trend is indicative of broader phenomenon across the continent’s telcos where voice and data revenues are crashing, cannibalized by apps like Whatsapp. Add to this the growth pressures of going public, and African telcos are increasingly looking to drive growth beyond the traditional airtime offerings. This puts them on an inexorable crash course with the banking industry.

Of course, banks will still have a central role to play in the shifting system, perhaps an intentional strategy by the CBN to not rock the boat too hard. Of all the cash circulating without ever passing through a formal bank (estimated at 80 percent in emerging markets), most of what PSBs collect will by law wind up in the traditional banking system, so the incentives for banks to jostle for the right PSB partnerships is strong. Though these partnerships will be unlikely to be directly profitable for banks, they will create monetizable opportunities for up-selling, not to mention greater financial health from an infusion of reserves and increased ability to lend. The question is thus not if banks will integrate into the digital finance ecosystem but how.

Calling All Integrators

As with any hands-off regulatory approach, the Nigerian model is one that puts the onus on private sector players to achieve the country’s financial inclusion targets. Ultimately, the success of the system as a whole may have more to do with collaboration among ecosystem players, who may each bring a different set of capabilities that collectively constitute the seamless transacting experience that could overcome the attachment to cash. Unfortunately, this will be no mean feat.

A big reason for Nigeria’s till now under-whelming financial inclusion can be summarized in one word: trust. One need not dig too deep to understand: the first thing anyone who tries to buy a Nigerian airline ticket online discovers is pop-up warnings to be wary of scam sites luring buyers with fake payment portals. These warnings are equally prevalent in physical form at the registers of private and public vendors alike; in most Nigerian railroad stations, for example, queues typically form before sunrise for those seeking to secure a seat, nominal availability of online ticketing notwithstanding. Even the staid banking system reportedly lost over USD $300 million a year between 2014 and 2017 through various fraud schemes.

In a word, trust is low because the exploitation of vulnerabilities in Nigeria is particularly high. Thus, despite the potential to over-regulate an emerging sector to death before it graduates from its infancy, CBN is likely to keep a strict eye on its license awardees’ operations and compliance.

To date, telcos maintain a fairly high perception of reliability in Nigeria - and many fintechs are actively combatting the trust issue head on by adopting radical transparency in their own finances. But for PSBs to get the additional one in five Nigerians threshold needed to achieve its initial financial inclusion targets, they will need to solve more than just perception challenges.

It is unlikely any single player will be able to achieve this alone, even the big telcos like MTN and Airtel. In fact, if Nigeria cleaves closer to the digital finance models of its East and West African counterparts, a bevy of third party providers will emerge around the ‘rails’ laid by the telcos and the venerable mobile money operators that have preceded them, offering value-adding services prohibited to PSBs like loans, insurance, or foreign exchange services. Though at this stage, CBN regulations remain ambiguous as to how such partnerships will may align with the limitations placed on PSBs themselves, there is certainly no lack of such players ripe for collaboration - nor lack of problems that demand solutions in value chains from logistics to agriculture.

Given CBN’s approach to tackling financial exclusion, it will have to do all they can to optimize the regulatory environment for collaboration if it wants to have at least as much to brag about as its Indian counterparts. By upping the ante with an even more ambitious financial inclusion target, Nigeria’s PSB bet has a lot riding on the successful integration of Nigeria’s telco giants into its hitherto insulated financial sector. While the fine print of the license and its relevant regulations continue to be drafted, CBN will have to promote collaboration in a low-trust environment on the one hand and write rules that enable profits even for bank-competitors on the other. If it succeeds in this, then all Nigerians will certainly have something to celebrate by 2024.

Image courtesy of MTN Nigeria

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight direct to your inbox.

Public Banking: Time To Make Room?

Remittances: Ending Cash-Out