The New Rules And Norms Shaping Alternative Data 2.0

~8 min read

The first wave of alternative data use gave rise to powerhouse companies across key markets in the African continent, particularly in East and West Africa. Allowing previously excluded adults to access credit and participate in the formal economy for the first time, the insights gleaned from alternative data spilled into areas like agriculture, insurance and logistics. Capitalizing on a variety of data points — from mobile money data to social media usage, contact lists, and for SMEs, data on items they stock and frequency of restocking — these and other companies have seen tremendous growth. Such innovation brought about unforeseen issues, however, especially regarding data management and access, where a lack of rules to govern the industry led to exploitation. Learning from these past mistakes and with regulations emerging, the existing and upcoming companies using alternative data must adjust their operations to survive. Digital lenders, in particular, will be expected to shift their models of calculating creditworthiness, as regulations limit their ability to utilize data without restrictions, shifting their approach towards obtaining consent from users and focusing on improving users’ financial well-being.

The Changing Landscape

Regulators have started to crack the whip on rogue alternative data companies, setting policies and frameworks to regulate the use and distribution of data. Nigeria’s Sokoloan was, for instance, fined $24,000 in 2021 for abusing user data, and it was later shut down by the Nigerian government on allegations of being an illegal financial institution. Consumer protection regulations in key African markets have evolved, following a similar path across the countries. Uganda is in its initial stages, collecting complaints from users of predatory practices witnessed by digital lenders and issuing warnings from government officials. Nigeria is slightly ahead, initiating an Interim Regulatory Framework and Guideline for Digital Lending, which digital lenders are required to abide by. This guideline acts as a first step toward forming clear regulatory frameworks. The next step would be to place the digital lenders under a regulatory body, effectively regulating it. Kenya has taken this step by placing digital lenders under the supervision of the Central Bank of Kenya and enacting new laws to regulate the industry. As part of the new regulations, limitations were set on the access and use of user phonebook contacts as well as the sharing of unpaid consumer debt data with third parties.

Capacity, Not ‘Willingness’ To Repay

Without the ability to use tactics such as reaching out to friends and family to shame borrowers into repaying loans, among other dubious tactics, digital credit providers are being forced back to the drawing board in order to change their business models. This is further necessitated by governments’ efforts to protect consumers from falling into debt traps.

Models in the microlending industry had been based on willingness to repay loans over capacity to repay. A shift away from this will require intensive data analytics to correctly map out and serve markets that may have little to no financial footprint in the digital economy. Consider the farmer who relies on cash transactions and owns a feature phone. The way to reach such a farmer with credit facilities has been with the use of data points like phone data (number of contacts) and psychometric tests from providers like LenddoEFL, demonstrated in their work with Juhudi Kilimo, a microfinance institution serving smallholder farmers.

Yet with such tests often focused on ‘willingness to repay,’ greater emphasis on customers’ financial outcome is leading to different models that can better analyze a farmer’s capacity to repay loans. Brazil’s CreDa utilizes AI to evaluate farmers’ yield potential as well as farm size and condition of crops to predict their yield and therefore their ability to repay a loan. Such innovation is also seen in Africa, like Zambia’s Agripredict, which allows farmers to identify and eliminate risks with their farm activities.

Potential partnerships with such agritech companies may prove vital for digital lenders to predict the capacity of loanees to repay loans. That is not to say that the willingness to pay will no longer have a role at all — especially pertaining to individuals or groups operating in the informal market — in kick starting a thin file, but diversifying data sources wherever they come in consented form will be critical.

While the human aspect has been largely replaced by algorithmic processes — save for the interpretation of data from the companies’ models — it may be necessary to reach the last mile when it comes to understanding the capacity to pay. Human intervention is often utilized to onboard digitally inexperienced people onto a platform, exemplified by JUMO’s mix of technology and human touch. Such an approach can be used to guide people through psychometric and behavioral tests that help determine capacity to repay loans.

Consent Is Now Sexy

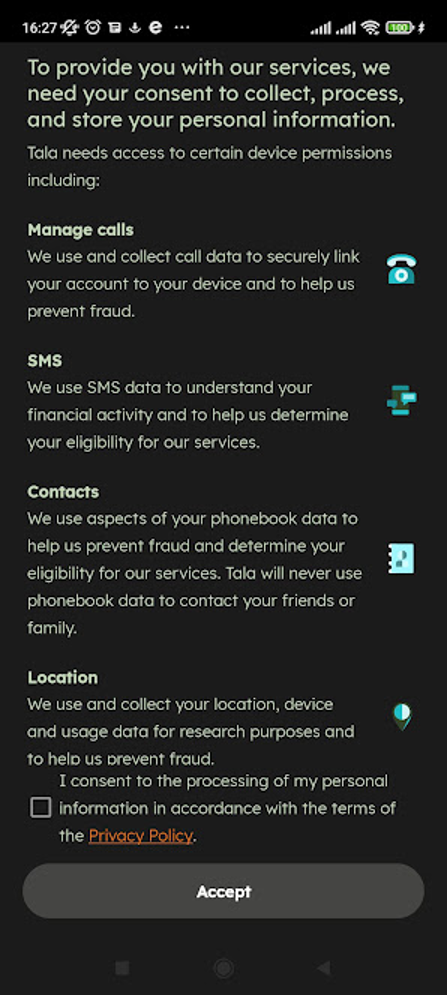

Alternative data 2.0 also focuses on improved communication and transparency — particularly in regards to seeking consent. JUMO, the digital lending platform operating in multiple countries, including Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia, seeks consent using local languages. At the same time, Tala includes a detailed screen with each data point used and why it's used, with the ‘Accept’ button at the bottom and a link to a more detailed version of their privacy policy. This is different from the previous trend of simply adding a marketing message and one line of text asking for consent, with links to the data privacy policy.

Source: Tala App

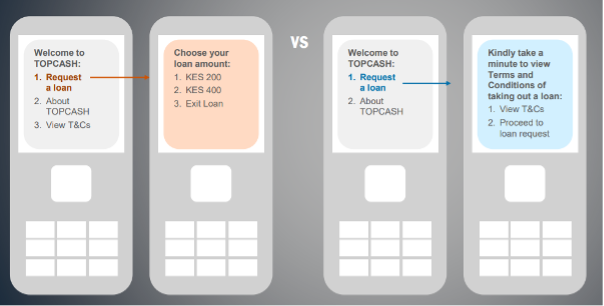

For feature phone users, consent can be sought in ways that encourage users to read through the terms and conditions of using the platforms. A shift from providing the policy guidelines as an option to adding them as a natural next step when one shows interest in applying for a loan may be crucial to ensure that people are aware of the data points they are providing.

Source: CGAP

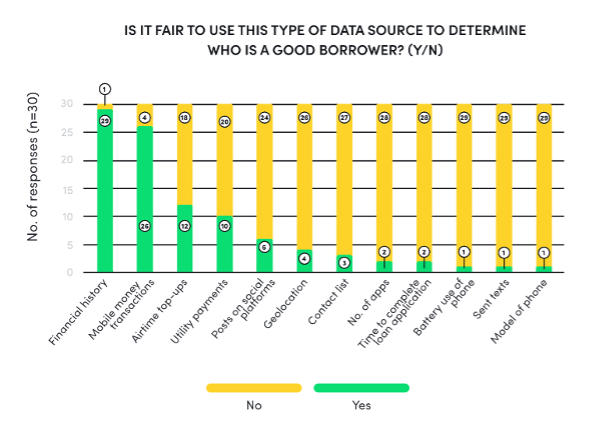

More reforms on the way firms seek consent are expected as understanding on how people interact with the platforms increases. Consent requires a user to understand what they have agreed to — a condition that is rarely met, but especially so regarding users in informal markets. A survey conducted by the Center for Financial Inclusion (CFI) in Rwanda found that a majority of respondents were against the use of certain types of data mining by digital lenders, in particular disagreeing with the use of contact lists, sent texts, phone models and battery use of phones. Yet users continue to sign up for digital lending platforms that use these same data points to determine credit scores — even when such use is stated during the sign-up process.

Source: CFI

Desperation or a lack of options at the time of sign-up are two significant reasons, but a lack of understanding is also to blame. Mondato reached out to digital lending app users in Nigeria to inquire about their understanding of the data policies. Ebere, a middle-aged Nigerian woman, shared her understanding when shown the above screenshot from Tala’s App.

“For me, I would expect that they will read loan repayment SMSs, and that is acceptable as how else are they to know if I paid or not?”

Ebere, Mobile Loan App User, Nigeria

Ebere said that she felt safer with the addition of the clause that none of her friends would be contacted due to her non-repayment of a loan, expressing more concern for that than the app’s ability to access key private data.

After several years of the industry facing criticism and subsequently enacting reforms, as Mondato discussed last year, users are becoming more conversant with how their data is used, though there is still a ways to go. As government regulations and user expectations continue to progress, companies will be further compelled to include more information, such as a breakdown of loan repayment plus interest rates in easy to understand terms, before the loan is provided.

Qualifying And Quantifying Impact

Alternative Data 2.0 will also likely see a reemphasis on improving the financial outcomes for users — not only from a reputation standpoint, but in ensuring consistent, reliable income streams. Graduates of the zero-file or thin-file basket into higher-tier services provide a lower-risk clientele for digital lenders, with easier to predict behavior thanks to an established financial footprint. This makes measuring the impact of products on users essential. Industry players have begun to set up processes that capture people's behavior after receiving and utilizing loans. According to JUMO’s Chief Analytics Officer, Paul Whelpton, JUMO’s algorithms capture loan usage behavior through wallet data, clustering customers into tiered groups based on loan limits and repayment frequencies. This allows them to also look at users’ movement from one tier to the other, indicating increased financial capacity.

Pezesha’s CEO, Hilda Moraa, also emphasized the need to measure impact while giving a public speech in Nairobi, citing it as critical to Pezesha’s success. For Pezesha, the impact is seen when the platform’s users, primarily small business owners in informal markets, start to inquire about more sophisticated products, such as larger loans beyond what Pezesha offers and insurance for their businesses.

However, despite a focus on impact and properly measuring it, applicants’ workarounds to access services cannot be underestimated. While digital lenders lower their risk by starting users on small loan amounts — about $15 or lower — some have found ways around this. Gale, a user of digital lending platforms from Ghana, describes friends that take out loans multiple times from one lender to increase their limit or take loans from multiple lenders, using one to pay the other just to create a credit history, also known as ‘spinning.’ Such cases could wrongly be interpreted as growth or increased wealth creation by lenders, though companies are now adjusting to such tactics.

“We use wallet data to analyse customer repayment frequency. Higher frequency borrowers will get slower progression and loan offers to encourage normalized loan behaviour.”

Paul Whelpton, Chief Analytics Officer, JUMO

Whelpton further describes the need for qualitative data when measuring impact to ascertain growth as captured by data models.

Partnerships For Survival

Further developments may see businesses forced to seek other data sources as users better understand the kind of data used to avail loan services. For instance, the use of social media behavior data may soon not be acceptable, as people pick out the data, they are comfortable sharing with digital credit providers. But companies weaning themselves off such data might find recourse elsewhere. JUMO, a platform that enables people to access credit from its banking partners, continues to garner success while staying away from social media as a data source, instead relying on sources such as mobile network operators. Increasingly, partnerships are being utilized to access larger data pieces. Pezesha, a digital finance company that serves SMEs, partners with Marketforce and TwigaFoods providing it access to the companies’ merchants and merchant data that can then be used to inform their models. The two companies, on the flip side, access Pezesha’s credit scoring system to help provide loans to their customers. Working in tandem to mine for data via external sources, companies like JUMO have created platforms that let them collect customer data from within the platform to inform algorithms as the users interact with the platforms. This allows thin-file users to grow their credit profiles as they take and repay loans, thereby reducing their reliance on proxies for credit scoring, though such companies admittedly still can’t quite compensate for the data they’ve lost.

Future Updates

Following in the footsteps of the EU, what can be expected is a move toward giving individuals more control over their personal data. While data activists press forward with ambitious paths for compensation in exchange for personal data, a shift in ownership and control of data is beginning to take root, starting with health care. AfyaRekod, a healthcare platform with operations in South Africa and Kenya, aims to return ownership of health records to patients with the help of blockchain technology. Patients can collect and access their health records through AfyaRekod’s personalized portals, reducing time spent hunting for records across multiple hospitals in a place where the records are often left with the hospital.

Such a categorical shift requires significant regulatory overhaul that takes years to execute. Yet empowering individuals to control their data — to protect, share and even be compensated for it — is the only course that can manage to supply the requisite alternative data while satisfying privacy concerns. In this sense, alternative data 2.0 is certainly more of an intermediate than final version — but it’s less buggy than 1.0 was.

Image courtesy of Luke Chesser

Click here to subscribe and receive a weekly Mondato Insight directly to your inbox.

Mobile Money In Zimbabwe: Shaken, But Still Standing

Gambling And Fintech: Two Sides Of The Same Coin?